Topics

12/10/2017

Wealthy People Get Fat? Poor People Get Fat?

-

Contents

-

- Wealth is said to be the cause of obesity....

- The case of poverty and obesity

- Why were they fat?

- Though we have become wealthy, how is the quality of our food? My thoughts

I would like to share with you an interesting story based on profound research that is also relevant to my theory. I will conclude this post with my thoughts.

【Related article】The Combination of Thin and Overweight in the Same Poor Group Is Not Contradictory

1. Some believe that wealth is said to be the cause of obesity...

"Ever since researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) broke the news in the mid-1990s that the epidemic was upon us, authorities have blamed it on overeating and sedentary behavior and blamed those two factors on the relative wealth of modern societies.

■'Improved prosperity' caused the epidemic, aided and abetted by the food and entertainment industries, as the New York University nutritionist Marion Nestle explained in the journal Science in 2003.

'They turn people with expendable income into consumers of aggressively marketed foods that are high in energy but low in nutritional value, and of cars, television sets, and computers that promote sedentary behavior. Gaining weight is good for business.'

■The Yale University psychologist Kelly Brownell coined the term 'toxic environment' to describe the same notion.

Just as the residents of Love Canal or Chernobyl lived in toxic environments that encouraged cancer growth, the rest of us, Brownell says, live in a toxic environment 'that encourages overeating and physical inactivity.'

'Cheeseburgers and French fries, drive-in windows and supersizes, soft drinks and candy, potato chips and cheese curls, once unusual, are as much our background as tree, grass, and clouds. Computers, video games, and televisions keep children inside and inactive,' he says.(*snip*)

▽The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the identical logic to explain the obesity epidemic worldwide, blaming it on rising incomes, urbanization, 'shifts toward less physically demanding work...moves toward less physical activity...and more passive leisure pursuits.'

Obesity researchers now use a quasi-scientific term to describe exactly this condition: they refer to the 'obesigenic' environment in which we now live, meaning an environment that is prone to turning lean people into fat ones."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 17-8.)

In Japan as well, this idea is widely accepted, and most experts on television explain that overeating and physical inactivity are the causes of obesity.

2. The case of poverty and obesity

However, what we have to consider here is that obesity is spreading in the poor layers of society, too.

"One piece of evidence that needs to be considered in this context, however, is the well-documented fact that being fat is associated with poverty, not prosperity-certainly in women, and often in men. The poorer we are, the fatter we're likely to be. (*snip*)

In the early 1970s, nutritionists and research-minded physicians would discuss the observations of high levels of obesity in these poor populations, and they would occasionally do so with an open mind as to the cause.(*snip*)

This was a time when obesity was still considered a problem of 'malnutrition' rather than 'overnutrition,' as it is today."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 18, 29.)

"Between 1901 and 1905, two anthropologists independently studied the Pima (Native American tribe in Arizona), and both commented on how fat they were, particularly the women.

Through the 1850s, the Pima had been extraordinarily successful hunters and farmers. By the 1870s, the Pima, however, were living through what they called the 'years of famine.' (*snip*)

When two anthropologists (Russell and Hrdlička) appeared, in the first years of the twentieth century, the tribe was still raising what crops it could but was now relying on government rations for day-to-day sustenance.

What makes this observation so remarkable is that the Pima, at the time, had just gone from being among the most affluent Native American tribes to among the poorest.

Whatever made the Pima fat, prosperity and rising incomes had nothing to do with it; rather, the opposite seemed to be the case. (*snip*)

(A quarter-century after Russell and Hrdlička visited Pima)

Two researchers from the University of Chicago studied another Native American tribe, the Sioux living on the South Dakota Crow Creek Reservation.

These Sioux lived in shacks 'unfit for occupancy,' often four to eight family members per room. Many had no plumbing and no running water. Forty percent of the children lived in homes without any kind of toilets. Fifteen families, with thirty-two children among them, lived "chiefly on bread and coffee.' This was poverty almost beyond our imagination today.

Yet their obesity rates were not much different from what we have today in the midst of our epidemic : 40 percent of the adult women on the reservation, more than a quarter of the men, and 10 percent of the children, according to the University of Chicago report, 'would be termed distinctly fat.'"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 20-24.)

1950-1980’s

This combination of obesity and undernutrition existing in the same populations have been found and reported from around the world, including the West Indies, South Africa, Chile, Ghana, and Jamaica.

3. Why were they fat?

<About the case of Manhattanites, in the early 1960's>

"This was first reported in a survey of New Yorkers-midtown Manhattanites-in the early 1960s: obese women were six times more likely to be poor than rich; obese men, twice as likely. (*snip*)

Can it be possible that the obesity epidemic is caused by prosperity, so the richer we get, the fatter we get, and that obesity associates with poverty, so the poorer we are, the more likely we are to be fat?

It's not impossible. Maybe poor people don't have the peer pressure that rich people do to remain thin. Believe it or not, this has been one of the accepted explanations for this apparent paradox.

Another commonly accepted explanation for the association between obesity and poverty is that fatter women marry down in social class and so collect at the bottom rungs of the ladder; thinner women marry up.

A third is that poor people don't have the leisure time to exercise that rich people do; they don't have the money to join health clubs, and they live in neighborhoods without parks and sidewalks, so their kids don't have the opportunities to exercise and walk.

These explanations may be true, but they stretch the imagination, and the contradiction gets still more glaring the deeper we delve."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page18-19)

<About the case of the Pima (Native American tribe in Arizona >

"So why were they fat? Years of starvation are supposed to take weight off, not put it on or leave it on, as the case may be. And if the government rations were simply excessive, making the famines a thing of the past, then why would the Pima get fat on the abundant rations and not on the abundant food they'd had prior to the famines?

Hrdlička also thought that their physical inactivity was the cause of obesity because they were sedentary in comparison with what they used to be. This is what Hrdlička called 'the change from their past active life to the present state of not a little indolence.' But then he couldn't explain why the women were typically the fat ones, even though the women did virtually all the hard labor in the villages—harvesting the crops, grinding the grain, even carrying the heavy burdens.

▽Perhaps the answer lies in the type of food being consumed, a question of quality rather than quantity.

This is what Russell was suggesting when he wrote that 'certain articles of their food appear to be markedly flesh producing.'

The Pima were already eating everything 'that enters into the dietary of the white man,' as Hrdlička said. This might have been key.

The Pima diet in 1900 had characteristics very similar to the diets many of us are eating a century later, but not in quantity, in quality."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 22-3.)

4. Though we say we have become wealthy, how is the quality of our food? My thoughts

I want to explain my consideration based on numbers one to three.

First of all, when considering "obesity," isn't it too simplistic to think that obesity has increased since we have become wealthier?

It is true that our lives are wealthier than we used to be in terms of freedom of choice and an abundance of goods. If we have a certain income, we can do what we like and eat what we want.

However, when the income is low, we can’t spend a lot for food. Also, we don’t have enough time to eat, since many of us are so busy at work or with household chores.

We might eat an unbalanced diet leaning toward carbohydrates (and not enough vegetables) such as eating toast and coffee for breakfast, and a burger or a cup of noodles for lunch. We might skip breakfast or lunch.

In addition, those who gain weight easily try to eat a simple light meal or skip a meal, since they ate a lot the day before. The idea of offsetting an over-intake of calories from yesterday, eating less today, is wrong.

That is to say, even if someone is said to be wealthy, with regards to food, there are many things in common with groups that live in poverty with a high rate of obesity. As Mr. Taubes says, what is important now is the “quality” of food rather than the “quantity.”

In an extreme argument, obesity with poverty can be explained by the same mechanism that people who are on a diet end up gaining more weight after they stop dieting, even though they reduced the caloric intake.

"Not all of us get fat when we eat carbohydrates, but for those of us who do get fat, the carbohydrates are to blame; the fewer carbohydrates we eat, the leaner we will be.

(*snip*)

These foods are also, almost invariably, the cheapest calories available. This is the conspicuous explanation for why the poorer we are, the fatter we're likely to be"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 134-5.)

12/07/2017

After Gaining Weight, We Eat Too Much and Do Less Exercise

-

Contents

-

<Prologue>

- Rats don’t get fat from eating too much

- Example of not enough exercise after getting fat

Prologue

"The experts who say that we get fat because we overeat or we get fat as a result of overeating - the vast majority - are making the kind of mistake that would (or at least should) earn a failing grade in a high-school science class.

They're taking a law of nature that says absolutely nothing about why we get fat and a phenomenon that has to happen if we do get fat - overeating - and assuming these say all that needs to be said."

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why we get fat. New York: Anchor Books, Page 76.)

This is the foundation I started writing my blog on. I’m sure that there are at least a few researchers in the world who think the same way as I do.

Even if someone insisted that, “the Earth is going around the Sun” in the sixteenth or seventeenth century where "geocentric theory" was the prevailing thought, no one would have believed him.

Many should have argued that, “if the Earth is going around the sun, our heads should go around, too.” However, now, it’s common sense that the Earth is going around the sun.

In the same way, many might not believe me when I say, “people can gain weight by intestinal starvation and it is the fundamental cause of being overweight.” However, I believe it’s the truth.

1.Rats don’t get fat from eating too much

It is said that, “eating too much and not enough exercise are the causes of gaining weight,” but here is an interesting experiment that is related to it.

"In the early 1970s, a young researcher at the University of Massachusetts named George Wade set out to study the relationship between sex hormones, weight, and appetite by removing the ovaries from rats (females,obviously) and then monitoring their subsequent weight and behavior.

The effects of the surgery were suitably dramatic: the rats would begin to eat voraciously and quickly become obese.The rat eats too much, the excess calories find their way to the fat tissue, and the animal becomes obese. This would confirm our preconception that overeating is responsible for obesity in humans as well.

But Wade did a revealing second experiment, removing the ovaries from the rats and putting them on a strict postsurgical diet. (*snip*) The rats, postsurgery, were only allowed the same amount of food they would have eaten had they never had the surgery.

What happened is not what you'd probably think. The rats got just as fat, just as quickly. But these rats were now completely sedentary. They moved only when movement was required to get food. (*snip*)

The way Wade explained it to me, the animal doesn't get fat because it overeats, it overeats because it's getting fat. The cause and effect are reversed.

(*snip*)

The evidence that fat tissue is carefully regulated, not just a garbage can where we dump whatever calories we don't burn, is incontrovertible.(*snip*)

Those who get fat do so because of the way their fat happens to be regulated and that a conspicuous consequence of this regulation is to cause the eating behavior (gluttony) and the physical inactivity (sloth) that we so readily assume are the actual causes."

(Taubes. Why we get fat. Page 89-90, 93-4.)

<1970s>

Words of Bruce Birstrian who conducted a treatment of a low-calorie diet (600kcal/day) to thousands of obese patients at Harvard University of Medicine.

"Undereating isn't a treatment or cure for obesity; it's a way of temporarily reducing the most obvious symptom. And if undereating isn't a treatment or a cure , this certainly suggests that overeating is not a cause."

(Taubes. Why we get fat. Page 39.)

My experience is a little different from the rats’ story, but I want to tell of my experience that I gained weight not because of eating more.

When I was very thin, under forty kilograms, I couldn’t eat a lot since my stomach always felt heavy. Fatty foods and oily foods were the worst. I tried hard to gain weight, but I couldn’t.

One day, I realized that I could gain weight by eating only easy-to-digest foods (mainly carbs and a little meat) and experiencing being hungry for hours. So, I tried to eat light meals for breakfast and lunch, and I tried not to eat vegetables and fat very much until dinner. By doing so, I gradually gained weight. And when I weighed about fifty kilograms, I had more muscle and less discomfort in my stomach. I was able to eat more than before.

Those who didn’t know my experience told me, “You’re gaining weight because you’re eating more,” but that wasn’t true.

After my body adjusted to my new eating plan, I gained weight little by little by eating. As I gained weight, I gradually gained more muscle and my appetite increased. As a result, I was able to eat more than before. So, the reality was the other way around.

▽Maybe it’s easier for you to imagine with an extreme example.

Let’s say there is a big man who is three meters tall and weighs two-hundred-fifty kilograms. If he eats five times as much food as we do, we would not think that he has grown big because he eats so much. Rather, we would think, "He is able to eat that much because he is so big.”

"Just prior to the Second World War, European medical researchers argued that it is absurd to think about obesity as caused by overeating, because anything that makes people growーwhether in height or in weight, in muscle or in fatーwill make them overeat.

Children, for example, don't grow taller because they eat voraciously and consume more calories than they expend. They eat so muchーovereatーbecause they're growing."

(Taubes. Why we get fat. Page 9.)

2.Example of not enough exercise after getting fat

"Some people find it hard to get their head round the fact that aerobic exercise is not particularly effective for weight loss, even when faced with all the facts.

One reason for this is our experience of seeing physically fit and active individuals who are clearly lean.

Look at any elite long-distance runner or Tour de France cyclist and you're probably getting a glimpse of what it's like to have a single-digit body fat percentage. The automatic thought process is that exercise causes leanness.

However, could it that individuals who are naturally lean are simply more likely to end up as elite long-distance runners or cyclists? In other words, might their natural leanness cause certain people to be more active, rather than the other way round?

There's actually some evidence for this. In one piece of research, the relationship between physical activity and body fatness in children over a 3-year period was assessed. It was found that the more sedentary children were, the more fat they carried.

This is all to be expected, but because the study was conducted over a prolonged period the researchers were able to gauge whether sedentary behaviour preceded weight gain.

Actually, it did not. In reality, children accumulated fat first, and then became more sedentary.

The authors noted that this finding 'may explain why attempts to tackle childhood obesity by promoting PA [physical activity] have been largely unsuccessful'. "

(Jone Briffa. 2013. Escape the Diet Trap. London: Fourth Estate, Pages 223-4.)

I agree with this opinion, but I’d like to add my own opinion.

As Dr. Briffa said, I think it’s reasonable to think those who are slim aim to be marathon athletes or soccer players, etc. They at least know that they can eat a lot and not get fat. So they will eat whatever they want without hesitation, won’t they?

In other words, by eating balanced foods every meal, intestinal starvation doesn’t happen —by that, I mean their set-point for body weight doesn’t change—and they keep their current weight while getting a little more muscle.

On the other hand, when people stay at home, spending time relaxing with a book or watching television, or when doing office work or light physical labor, don’t they tend to eat less or lighter meals?

Sometimes, they may eat only light meals such as hamburgers, hot-dogs, or instant noodles for lunch. Since they don’t exercise, they don’t pay attention to eating balanced and nutritious meals.

If their diet leans toward easily digestible carbs and some protein and they are experiencing being hungry for hours, the intestinal starvation mechanism may occur and their set-point weight will go up. They end up gaining more weight.

To sum up, I’d like to say that not enough exercise or laziness won’t directly cause people to get fat. The intensity and amount of physical activity will affect the amount of food you eat as well as food choices.

09/28/2017

What Does It Mean to Eat Relatively Less?

Contents

- An example of judo

- An example of delivery center

- An example of food

<The bottom line>

I always felt something was wrong, when I was having lunch with my coworker K, who is about eighty kilograms. He said to me, “You have to eat more in order to gain weight”, because I was very thin.

However, he was eating the same thing as I was. It’s just that he had a little more rice than I.

Why It felt odd was that "K was eating relatively less" and " I was eating relatively more " in terms of quality and quantity.

1. An example of "judo"

First, I’d like to explain by using the Japanese sport of judo. There are usually wrestlers of forty-five, sixty, and up to ninety kilograms mixed weight groups at a practice.

The forty-five kilogram wrestler often works with those who are heavier than him, so he will be practicing relatively hard. In particular, if he practices with a ninety kilogram wrestler, there is twice the difference of weight, so it’s difficult to win.

On the other hand, for the ninety kilogram wrestler, it’s a practice which is relatively easy, since there are only those who weigh less than him. Even if they do the same practice, the level of challenge is different for each wrestler.

2. An example of delivery center

Let’s see it again here by using a “delivery center” example. A delivery center is a place where they sort packages and send them out everyday. There are two delivery centers. Center A has a capacity of five hundred packages, and delivery center B has a capacity of eight hundred packages.

When there are five hundred packages being processed, A will be at its limit, but B still has some room.

When there are seven hundred packages being processed, A is over its capacity, so employees have to work overtime, but B still has some room.

That is to say, even if the quantity of packages is the same, the things happening inside differ by their capacity. If this were food, then the package would be equivalent to the “intake amount of food.”

3. An example of food

I guess you already know what I want to say. Here again, we have three ladies of different weights eating the same thing. A: 90kg, B: 60kg, C: 45kg.

Let’s say all three had the same hamburger set for lunch.

In terms of the food intake, all of them have the same amount and calories, but when we take their weight into account, C, who is forty-five kilograms is eating relatively more, and A, who is ninety kilograms is eating a relatively light meal.

It’s because A who is ninety kilograms has a body twice as large as C, with a thicker chest and a bigger stomach. You can also say that she might have a stronger digestive ability compared to B or C.

Here, when we focus on body size, you can say, “A is eating quantitatively less." When we focus on digestive ability, “A is eating qualitatively simpler than C.

“Qualitatively” means that those with a stronger digestive ability can digest the same amount of food faster, even if they are the same body size. For example, it's been said that Caucasians generally have stronger digestive enzymes for protein and fat, compared to many Asian people.

Now, suppose A orders a large bowl of rice. Regarding intake amount, you might think, “after all, she must be fat because she eats a lot.”

However, if we take their weight into account, since rice is a carbohydrate which is easy to digest, it can be said that A is still eating relatively less and eating a lighter meal compared to B or C.

The bottom line

(1) Based on my intestinal starvation theory, people who have a bigger body or stronger digestion eat relatively less or lighter meals compared to thin people. They are more likely to feel hungrier, and depending on what they eat, they are prone to inducing intestinal starvation and gain more weight.

(2) Also, assuming that European, American, or African people generally have a stronger digestion for fat and protein compared to many Asian people, they are more likely to gain weight than many Asians, even if everyone eats the same. It’s not that they have particular obesity gene.

09/10/2017

Eating Fat/Oil Can be a Deterrent to Gaining Weight (3 Perspectives Regarding Fat)

Contents

- Low-fat diets didn’t make people slim

- Three perspectives regarding dietary fat

(1) Sustained energy

(2) Deterrent effect of gaining weight

(3) Diet effect

<The bottom line>

Many people say that eating too much fat or oil makes you fat, since fat has more than twice as many calories as carbohydrates or proteins per gram. But some research shows that some people can lose weight even though they increase fat or oil in diets.

Which is true?

To make a long story short, I think both are correct. As I have mentioned so many times before in this article, there are two meanings to the phrase “gain weight,” and based on my theory, I can say that eating fat has three sides to it.

1.Low-fat diets didn’t make people slim

John Briffa, a British doctor and the author of “Escape the Diet Trap,” observed that low-fat diets had no effect on losing weight and that a fat-rich diet is more effective to getting slim, while taking hormone secretion, etc. into account.

“Conventional wisdom dictates that a key to successful weight loss is to keep the diet low in calories, and a key strategy deployed here is to cut back on fat. Fat contains twice as many calories as carbohydrate or protein. It's also called fat, of course. These facts do, on the face of it, seem to incriminate fat as something inherently fattening.

As a result, past attempts at weight loss may well have had you consuming enough skimmed milk and skinless chicken breasts to last you a lifetime.

On the other hand, many individuals will have had the experience of filling up on fat-packed foods such as eggs, cream, cheese and butter on ‘low-carb' regimes (such as the Atkins Diet), only to see their own fat melt away. Such experiences should, if nothing else, cause us to question the widely held belief that the fat we put in our mouths is destined to end up in the fat stores within our body.”

(Jone Briffa. 2013. Escape the Diet Trap. Page 51.)

He concluded :

- Low-fat diets are ineffective for weight loss.

- Dietary fat intakes are not strongly linked to body weight, and some evidence links increased fat intake with lower body weight.

- Insulin is the key driver of fat accumulation in the body. Dietary fat does not stimulate insulin secretion directly, and therefore has limited fattening potential.”

- Obviously, eating nothing but fat is not to be advised, but some study open up the possibility that a fat-rich diet may actually assist our weight-loss efforts[1].

I’m not a specialist or researcher. Therefore, I’d like to avoid mentioning how insulin or other hormones work in the bloodstream. But I believe I can explain why low-fat diets are ineffective for weight loss vs fat-rich diets that may help our weight-loss efforts, based on my theory.

I will explain in the next section.

2. Three perspectives regarding dietary fat

Based on my experience, I believe that people who say they gained weight by consuming fat or those who say they lost weight, are both true. However, each only highlights one aspect of the properties of fat. Focusing solely on 'calories' can obscure these different aspects.

I can say that three different effects can be expected depending on the the subject of intake (who) and/or the way of intake (such as the amount and frequency).

(1) Sustained energy

Fat is an excellent energy source and provides nine calories per gram. It’s also said that fat has several other essential functions for our health, such as being used as components of cell membranes and hormones.

But fat takes longer to digest, compared to carbohydrates or proteins. Therefore, you can see these features below:

- Foods high in fat help keep a sense of being satiated.

- High-fat diets stay longer in the stomach, so they won’t increase blood sugar level rapidly.

- Fats sustain energy for a long time.

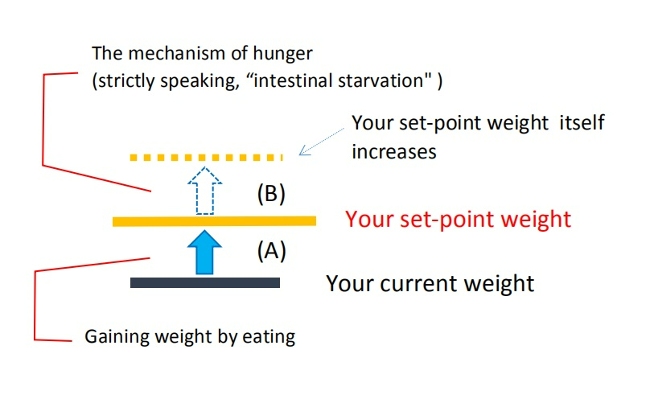

As you can see in the diagram regarding set-point weight, within the range of (A), if you eat many calories from fat with other foods containing carbs and protein, you should gain weight steadily.

People who have a higher digestive ability for dietary fat, especially those who are dedicated to dieting to keep their weight low or those aiming to shed excess fat to achieve a muscular physique, will get especially fat in a few days if they consume high-calorie foods like sweets, cakes, and deep-fried foods. The fattening effect seems especially acute when eaten with a good amount of carbohydrates or when having only two meals a day.

With these images, many people reject a revolutionary suggestion of taking fat/oil in order to get slim, and that’s what makes this theory hard to accept.

(2) Deterrent effect of gaining weight

As you can see in the range of (B) of the diagram above, when the set-point weight itself increases, fat will work as a deterrent force(*1). I’ve stated before that one's set-point for body weight increases by inducing intestinal starvation, and since fat takes longer to digest, if you frequently eat fat/oil, there will be less chance of triggering intestinal starvation.

(*1) For those who have a higher digestive ability for dietary fat, they may not experience a deterrent force.

In fact, fat digestion begins in the small intestine. When fat enters the duodenum, a hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK) is released, which promotes the digestion and absorption of fat.

However, at the same time, it is said that CCK inhibits gastric activity, which can lead to delayed gastric emptying, and food staying in the stomach for a longer period of time. For some people, this can lead to feelings of fullness and bloating.

In any case, fat digestion is more complex than other nutrients and tends to inhibit intestinal starvation.

For example, if a thin person wants to gain weight, eating a lot of fat/oil at meals will hinder gaining weight. Have you ever wondered, “why was he/she not getting fat despite the fact that they were eating high calorie foods, such as cakes, cookies, deep-fried foods, or fatty foods?”

In fact, a low-fat, easily digestible diet is more likely to make you gain weight in terms of increasing your set-point weight itself.

(3) Dieting effect (largely categorized within deterrent effect)

As Dr. Briffa whom I’ve mentioned above said, I also believe that "in a low-carb diet, increased fat intake is linked to lower body weight” is in a way correct, as though this doesn’t apply to everyone.

It is generally believed that the reason is that fat, unlike carbohydrates, does not stimulate insulin secretion, but I will avoid mentioning that for now. Other than that, here is what I would like to add and explain based on my theory.

The time it takes for fat to be completely digested can be six to eight hours, depending on the amount of food eaten and how we combine different foods. Therefore, by consuming fat/oil every four to five hours, undigested food will remain in the stomach and the large part of the intestines for most of the day, which lead to decreased feeling of hunger and, in turn, reduced absorption ability (rate and amount).

As seen in low-carb diets, by decreasing carbohydrate intake to an extent and increasing the intake of fats, proteins, nuts, and vegetables, etc., dense nutrients are delivered to the intestines, which takes even longer to digest. If you continue with this eating habit, I believe it maximizes the dieting effect.

[Related article]

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

The bottom line

(1) Just because fat has nine kilo calories per gram, does not mean that dietary fat always makes people fat.

For those who have a higher digestive ability for dietary fat, especially those who normally keep their weight lower to lose weight, eating fatty food can be a cause of weight gain, but depending on the subject of intake (who) and/or how you eat it (how much, how often), fat can have a deterrent effect to further weight gain or diet effect.

(2)Fat takes longer to digest than other nutrients, so if you frequently eat fat, undigested food tends to remain in the intestines. This makes intestinal starvation less likely to occur, which tends to deter further weight gain in the sense that one’s set-point weight doesn’t change.

(3)A diet low in carbohydrates but high in protein and fat may have a dieting effect. It is generally believed that the main reason is that fat, unlike carbohydrates, does not stimulate insulin secretion.

My theory, I would add, is that ingesting fats every four to five hours will leave undigested food in the wide range of intestines, which will lead to reducing feeling of hunger and, in turn, decreased absorption ability. Continuation of this condition could have a weight-loss effect.

References:

[1] Briffa J. Escape the Diet Trap. Pages 58-61.

06/10/2017

Dieting (Eating Less and Exercising More) Doesn’t Work in the Long Run

-

Contents

-

- It has nothing to do with lack of willpower

- What was the long-term effect of dieting

- Cognitive dissonance

It is said that exercising and food restriction is necessary for losing weight. However, we rarely meet those who succeeded in dieting using such a method.

Japanese wrestler Bull Nakano (below) has repeatedly dieted and rebounded, but after having knee problems, it was imperative that she lose weight, so she had a gastrectomy to remove part of her stomach.

She said that “cutting the amount of foods and exercising didn’t make her thinner.”

Japanese comedian, Sugi-chan lost seven kilograms with Billy’s Boots Camp diet method, but rebounded to the same weight afterward.

In this article, I would like to introduce how conventional calorie-based diets are ineffective, based on two books: "Escape the Diet Trap" and "Why Do We Get Fat.”

Please note that most of these are quotations.

1.It has nothing to do with lack of willpower

"Ideas about what causes obesity vary. But you'll almost certainly be familiar with the idea that, at the end of the day, the problem is a product of caloric imbalance: specifically, the consumption of calories in excess of those burned through metabolism and activity. No doubt you'll also be familiar with the idea that the solution to your weight problem is simply to redress the balance by eating less and exercising more.

This advice seems to make sense. The trouble is, not only our collective experience but scientific research, too, shows that applying this advice hardly ever brings significant weight loss in the long term.

The usual explanation offered here is that those who fail with conventional tactics lack willpower and self-control. The reality, though, is that calorie-based strategies for slimming not only don't work, but simply can't work, for all but a small minority.

‘Escape the Diet Trap’ explores the reasons why traditional approaches to weight loss are a crashing failure. It reveals how eating less and exercising more causes the body to resist weight loss, and can actually predispose to weight gain over time."

(Jone Briffa. 2013. Escape the Diet Trap. Pages 1, 19.)

2.What was the long-term effect of dieting

"Limiting the studies to those where individuals were monitored for at least two years after the start of their efforts to lose weight allows us to assess the long-term success of these approaches. Many of us will know what it is to get a short-term win from eating less and exercising more but it's the long game we're interested in here.

<Study1>

Individuals with an average age of 36 and average BMI of 35.0 were prescribed a calorie-reduced diet (individuals ate about 1,000 calories less each day than the amount needed to maintain a stable weight).

Some of the individuals added exercise to this dietary restriction in the form of brisk walking for 45 minutes, 4-5 times each week.

The intervention lasted for a year, and weight was assessed another year after the end of the intervention.

Two years after embarking on a long-term (lasting at least a year) restrictive dietary regime, average weight loss was in the order of just 2 kg. Even when regular exercise is added, the weight loss still only averaged about 3 kg (about 6 lbs).

These outcomes look even more paltry when put in the context of the weight of many of the study participants. For someone of average height, a BMI of 35 works out at about 16 stone. I'd say it's unlikely that individuals of this weight would view a loss of a few pounds as a satisfying return on investment in terms of their diet and exercise efforts.

Another potential surprise is just how ineffective exercise was for the purposes of weight loss when employed as an adjunct to dietary restraint. The results from these studies suggest an additional loss of a mere 1 kg in those who were exercising regularly."

(Briffa. Escape the Diet Trap. Pages 20, 22-3.)

"Prescribing low-calorie diets for obese and overweight patients, according to a 2007 review from Tufts University, leads, at best, to “modest weight losses” that are “transient” – that is, temporary. Typically, nine or ten pounds are lost in the first six months. After a year, much of what was lost has been regained.

The Tufts review was an analysis of all the relevant diet trials in the medical journals since 1980. The single largest such trial ever done yields the very same answer. The researchers were from Harvard and the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, which is in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and is the most influential academic obesity-research institute in the United States.

Together they enrolled more than eight hundred overweight and obese subjects and then randomly assigned them to eat one of four diets. These diets were marginally different in nutrient composition (proportions of protein, fat, and carbohydrates), but all were substantially the same in that the subjects were supposed to undereat by 750 calories a day, a significant amount.

The subiecte were also given “intensive behavioral counseling” to keep them on their diets, the kind of professional assistance that few of us ever get when we try to lose weight.

They were even given meal plans every two weeks to help them with the difficult chore of cooking tasty meals that were also sufficiently low in calories.

The subjects began the study, on average, fifty pounds overweight. They lost, on average, only nine pounds. And, once again, just as the Tufts review would have predicted, most of the nine pounds came off in the first six months, and most of the participants were gaining weight back after a year.

No wonder obesity is so rarely cured. Eating less –that is, undereating–simply doesn't work for more than a few months, if that."

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why We Get Fat. Page 36-7.)

3.Cognitive dissonance

"This reality, however, hasn't stopped the authorities from recommending the approach, which makes reading such recommendations an exercise in what psychologists call “cognitive dissonance,” the tension that results from trying to hold two incompatible beliefs simultaneously.

Take, for instance, the Handbook of Obesity, a 1998 textbook edited by three of the most prominent authorities in the field–George Bray, Claude Bouchard, and W. P. T. James.

“Dietary therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment and the reduction of energy intake continues to be the basis of successful weight reduction programs," the book says.

But it then states, a few paragraphs later, that the results of such energy-reduced restricted diets "are known to be poor and not long-lasting.” So why is such an ineffective therapy the cornerstone of treatment? The Handbook of Obesity neglects to say."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 37.)