Topics

01/07/2017

Reality Works Opposite of What and How We Think

This time, I would like to explain the relationship between the mind and the mechanism of gaining weight.

Some people who are overweight may start dieting with the thought, " I'm definitely going to lose a few kilos this year.” According to conventional calorie theory, the strategy to do so is to "eat less and/or exercise more.” Many of them first try to avoid high-calorie foods such as oily foods, fried foods, and sweets. Also, they try to skip meals or eat just a little in order to take in fewer calories. In addition to this, some may start jogging or go to a fitness club.

On the other hand, people who are thin tend to think, “I want to gain a little more weight” or “If I skip a meal, I will get thinner.” So, they try not to skip meals and try to eat foods with more calories even though they can’t eat a lot in one sitting.

Then why is it that obese people can’t lose weight even though they reduce caloric intake, but exercise? And why can’t thin people gain weight even though they eat a lot of calories?

It is possible that they are doing the opposite of what is really needed.

“Reality works opposite of what and how we think”

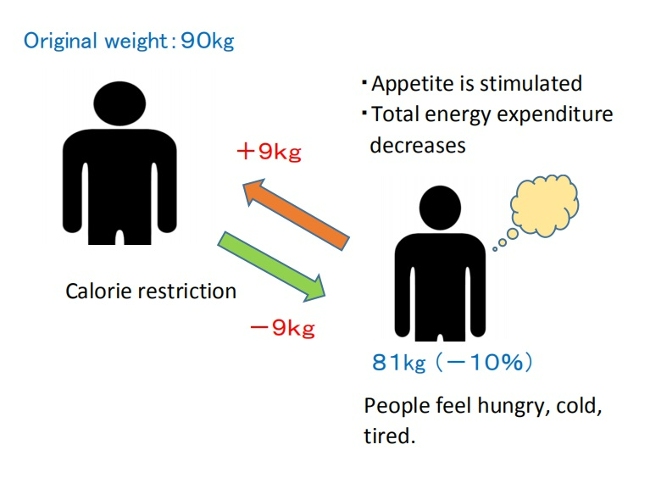

Obese people might get thinner for a while through eating less and exercising more. However, it’s a temporary thing, and over the long haul, it’s not that effective.

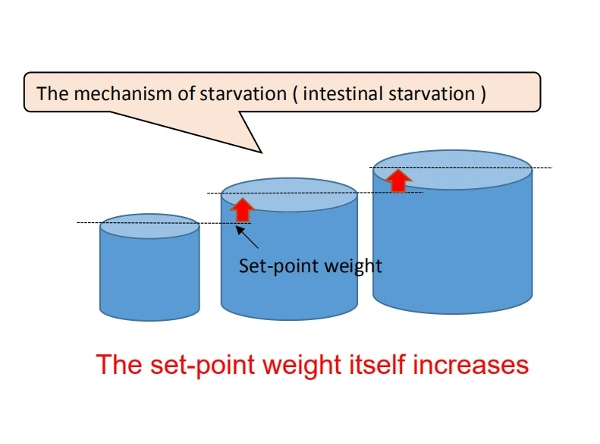

With the long periods of hunger caused by restricting meals as in a diet, the intestines improve their absorption ability in order to get the maximum absorption out of a small amount of food. If they don’t eat a balanced diet and their diet leans toward some digestible carbohydrates and protein, the intestinal starvation mechanism may occur. As a result, the 'set-poit' for body weight may go up unknowingly and they’ll find themselves gaining more weight than before. (The rebound effect).

So, it is natural that the success rate of calorie-restricted dieting is low, since they are dieting in the wrong way. It’s not because their efforts were not enough.

(Note: Of course, if you don’t eat anything and exercise, you will lose a lot of weight, but I don’t recommend it. If you don’t take any worthy nutrition when you are working out, the body will catabolize muscle and take minerals out of your bones.)

In contrast, when thin people skip meals, they soon start to get thinner in the face and get tired easily since they don’t have stamina. So, they believe they have to eat something even though they don’t feel so hungry. This is a natural way of thinking for creatures to live...

And that’s why many thin people tend to eat three meals a day and also eat high-calorie foods even if they don’t eat a lot. Also, some people snack between meals without hesitation. There are specialists and some websites that recommend they eat more calories to gain weight.

However, this makes intestinal starvation less likely to occur because undigested food remains in the intestines throughout the day, and the function of the body to store energy will not work. In short, the ‘set-point’ for body weight has not changed. Regardless of the calories they consume, they never gain weight, so they end up saying, “It’s the way I’m made.”

Generally, genetics are used as an excuse to explain the difference between people who eat a lot but never gain weight over the course of their life, and those who tend to gain weight even though they are dieting. Of course, genetics cannot be completely ignored, but since they are theoretically doing the opposite of what they need to do, it is not surprising that both do not work.

To begin with, we need to change the stereotype that "overeating and less exercise” are the causes of weight gain, to stop the obesity epidemic and discover something new.

10/17/2016

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

Contents

- An unbalanced diet and irregular eating rhythm can cause intestinal starvation

- This last, but not least important factor, what is “+one? ”

1. An unbalanced diet and irregular eating rhythm can cause intestinal starvation

I’ve stated before that what increases your set-point weight is the hunger mechanism (intestinal starvation) and here, I want to talk about three(+one) factors that accelerate intestinal starvation.

【Related article】→My Definition of “Intestinal Starvation”

In Japan, the reasons for gaining weight with the exception of calories are often said to be associated with:

■an unbalanced diet

・fast food/junk food

・too many carbohydrates

・lack of vegetables, etc.

■ irregular eating rhythm

・eating dinner late at night

・skipping breakfast or lunch

・snacking or not

When there is only one of the situations from above, the intestinal starvation mechanism hardly occurs. However, when there are three and the +one factor which I will discuss later, the mechanism for intestinal starvation happens more often.

The 3 factors are as follows :

- What you eat (quality and balance of food);

- the time you stay very hungry between meals;

- the ability to digest (stomach acid, digestive enzymes, etc).

Some say they gained weight from eating too many carbohydrates, but others won’t seem to gain weight even if they eat a lot of carbs.

Some say they gained weight by eating junk foods late at night, but others don't gain at all, even if they eat in the same way.

These differences exist since intestinal starvation is decided by the composition of various factors.

Explanation of (1)

1)What you eat (quality and balance of food)

・Low fiber intake ・Refined carbohydrates ・Digestible protein

・Processed food ・Fast food ・Junk food, etc.

Meals with mainly refined carbohydrates (starch) and some good protein (a small amount is enough) and less fiber intake from vegetables, make people fat most easily. It seems with less fat in the diet, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced. It’s because dietary fat slows digestion.

It doesn’t depend on the amount of calories you eat but the quality and balance of food you eat.

For example, eating a variety of foods and having a good balance vs a bad balance may lead to gaining weight, even if you eat in small amounts.

In contrast, balanced meals including vegetable fiber, dairy products, low G.I. foods, meat, and fat, etc., prevent inducing intestinal starvation.

*Eating speed, how many times you chew your food, or hydration during the meal, are also related to the above.

Explanation of (2)

2) The time you stay very hungry between meals

・Skipping breakfast or lunch ・Late dinner

・Number of meals per day ・Snacking or not

When we say we got fat due to an irregular eating rhythm such as late dinners or not eating breakfast, it means the problem is because of the time span between meals.

In other words, experiencing being hungry for a long period of time.

Eating late at night won’t automatically make you fat. If you have to eat a late dinner, you can snack (milk, chocolates, or sandwiches, etc.) between meals in order to prevent intestinal starvation.

Explanation of (3)

3) Digestive ability

・Strong/weak stomach ・Gastroptosis

・Difference of digestive enzymes

Those with strong stomachs and high digestive ability tend to induce intestinal starvation more rapidly than those with slow digestion.

This is because intestinal starvation doesn’t depend on the amount of food intake, but how fast the food is processed in the entire intestinal tract (or it might be a small intestine only).

It differs from person to person, but Individuals with a droopy stomach, or poor digestion might not be able to even induce intestinal starvation.

If there are genetic factors, the difference of digestive ability will be the first thing I will bring up as the factors. And it may vary between races as well as between families. (Of course, it may change after birth.)

2. This last, but not least important factor, what is “+one ?”

I stated that an important factor other than the above three factors is “+one,” but this can be explained by a “continuity,” which is whether you had an unbalanced diet (or a light meal) for your previous meal and the meals before that.

(Japanese typical breakfast we used to eat)

For example, you eat a light meal such as a hamburger and coffee for lunch, and then you can’t eat until 9 p.m. that night.

If you had also eaten a heavy breakfast with dairy, salad, seaweed, beans, or butter, you won’t experience a intestinal starvation (it depends on the person).

The reason for this is that the intestines are as long as seven to eight meters, so it takes the food more than ten hours to pass through.

Intestinal starvation is determined by the entire intestinal tract (or it might be the small intestine only), so the previous meal or the meals before that also affect it.

10/17/2016

Defining “Intestinal Starvation”: Its Relevance to the Multifactorial Model of Obesity

From an evolutionary biology perspective, humans and many other animals are thought to have developed mechanisms to cope with intermittent food shortages over long periods of evolution. Because periods of abundant food were limited, the ability to store energy in the liver, skeletal muscles, and adipose tissue was likely favored by natural selection.

From this viewpoint, obesity can be seen not merely as a consequence of overeating, but as a form of adaptive response in which the body stores energy when it perceives a risk of scarcity.

The concept of “intestinal starvation” adds a new perspective to the discussion of how our bodies perceive a lack of food, moving beyond the traditional focus on energy intake alone.

【Related articles】

Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

1.The definition of intestinal starvation

In this work, I use the term “intestinal starvation” to describe a physiological state in which all ingested food has been fully digested along the entire intestinal tract (*1). In this condition, the body interprets the absence of undigested material as a signal of “no food,”regardless of how much food was actually consumed.

This state should be distinguished from severe energy deficit or true food shortage. Unlike those extreme conditions, intestinal starvation may arise under ordinary living circumstances in relatively affluent societies, particularly when diets are dominated by easily digestible foods such as refined carbohydrates, fast-digesting proteins, and various ultra-processed foods (*2).

In this sense, it can be understood as a form of “modern hunger”: a perceived starvation—a signaling state—mediated by the gut–brain axis rather than by a lack of available food in the environment.

(*1) It is unclear whether intestinal starvation is sensed throughout the entire gut or only in the small intestine, which is sometimes referred to as the "second brain."

(*2) Since fats take longer to digest, consuming them every 4 to 5 hours may help prevent the onset of intestinal starvation (e.g., olive oil in the Mediterranean diet). However, during digestion, fats are emulsified into tiny droplets, and once fully digested, they leave no residual material in the gut. In individuals with strong fat-digesting capacity, especially when fats are consumed together with refined carbohydrates, this may not effectively suppress intestinal starvation (e.g., simple hamburgers, potato chips, donuts).

【Related articles】Eating Fat/Oil Can be a Deterrent to Gaining Weight

<Detailed explanation of “how much you eat”>

Even if you consume a large amount of food, a diet composed mostly of refined carbohydrates and other easily digestible items (including certain protein sources and small amounts of fat)—combined with long gaps between meals, such as eating only twice a day—can induce an intestinal starvation state or a condition very close to it.

When carbohydrates are consumed with water, they expand in the stomach (“balloon effect”), dilute the nutrient density of the meal (“dilution effect”), and then pass rapidly from the stomach into the intestine (“push-out effect”).

Because of these combined effects, the body may interpret all ingested food as being “fully digested,” even when a small amount of undigested material technically remains in the intestinal tract.

【Related articles】

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

(Refined carbohydrates)

Even when overall food intake is small, a diet composed mainly of easily digestible foods such as refined carbohydrates and certain protein sources (e.g., ultra-processed foods such as simple burgers or sandwiches, or instant noodles) may still trigger intestinal starvation.

Due to recent dieting trends, many people try to keep breakfast or lunch light in an effort to lose weight, but this approach may end up being counterproductive in the long run.

In contrast, when you eat a balanced diet including fiber-rich vegetables, and minimally processed foods three times a day, some fraction of undigested material remains in the intestinal tract continuously throughout the day, making it less likely for intestinal starvation to be induced.

2. Obesity’s multifactorial roots and intestinal starvation

Recent increases in obesity are often attributed to overeating and lack of physical activity.

However, even in environments with abundant food, some people maintain a slim body without dieting, while severe obesity is also observed even among low-income populations in developed countries and in Pacific Island nations with limited resources.

These observations suggest that obesity is a multifactorial condition that cannot be explained by a single factor[1,2]. Genetic factors, diet, physical activity, gut environment, and hormones all interact to influence body weight.

(Source: Freepik)

Since human genes are unlikely to change dramatically over just a few decades, changes in lifestyle and food environments since the 1970s are thought to have played a major role in the recent global rise in obesity[3].

Strictly speaking, four factors(*1) need to overlap for intestinal starvation to be triggered, which may explain why obesity is more likely to occur at the intersection of multiple factors, including genetic, environmental, and physiological factors.

(*1) The four factors are “what you eat,” duration of hunger, digestive ability, and continuity.

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

(1) Genetic factors

Genetic traits related to intestinal starvation include the secretion capacity and receptor sensitivity of enzymes and hormones that regulate digestion and appetite. In particular, populations or ethnic groups with a greater ability to digest proteins and fats rapidly may be more susceptible to intestinal starvation.

These characteristics may also change as a result of acquired conditions, such as obesity or gastric reduction surgery performed for weight loss.

(2) Environmental factors

Since the 1970s, one of the most notable environmental changes, I believe, has not merely been the increase in energy-dense foods, but rather the rise in easily digestible foods resulting from industrialized food production. Examples include refined carbohydrates, certain protein sources, and ultra-processed foods.

In vegetables and grains, the less digestible parts have been removed (e.g., refined grains), and some are now mashed or strained (e.g., mashed potatoes and potage soups). Meat and fish are often minced or ground, making them easier to digest.

(Author: brgfx / Source: Freepik)

These foods are digested and absorbed more rapidly than traditional, minimally processed foods. As a result, the body can obtain energy more efficiently with less effort, which may also contribute to increased hunger and reduced satiety.

This trend is observed not only in developed countries but also in emerging economies, where the increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods has been linked to rising obesity rates.

【Related article】

The Rise in Obesity is Closely Linked to the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods

<Lifestyle>

Intestinal starvation is related not only to what people eat but also to "how they eat."

Since the 1970s, changes in lifestyle have been accompanied by dramatic shifts in eating habits. In Japan, for example, the traditional rice-based breakfast has gradually been replaced by a Western-style breakfast consisting of toast, coffee, and fried (or boiled) eggs, etc.

In addition, many people now tend to eat light breakfasts and lunches, while consuming the majority of their daily calories at dinner. Such eating patterns may promote intestinal starvation, because our intestines are about seven to eight meters long, and all ingested food may be completely digested while traveling through the intestinal tract.

(3) Physiological factors

Intestinal starvation represents an adaptive physiological response related to intestinal processing and hormonal secretion, and may prove that people who eat a balanced diet every day are likely to be less prone to weight gain

Although intestinal starvation may not be directly associated with the gut microbiota, the types of foods consumed have a significant impact on the intestinal environment.

Individuals who eat a wide variety of foods in a well-balanced manner are less likely to induce intestinal starvation, which may indirectly suggest a relationship that those with a healthier gut microbiota are less susceptible to obesity.

<References>

[1]Flores-Dorantes MT, Díaz-López YE, Gutiérrez-Aguilar R. Environment and Gene Association With Obesity and Their Impact on Neurodegenerative and Neurodevelopmental Diseases. Front Neurosci. 2020 Aug 28;14:863.

[2]Khan MJ et al. Role of Gut Microbiota in the Aetiology of Obesity: Proposed Mechanisms and Review of the Literature. J Obes. 2016;2016:7353642.

[3] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Page 21-2.

03/15/2016

Two Meanings to the Phrase "Gaining Weight"

Contents

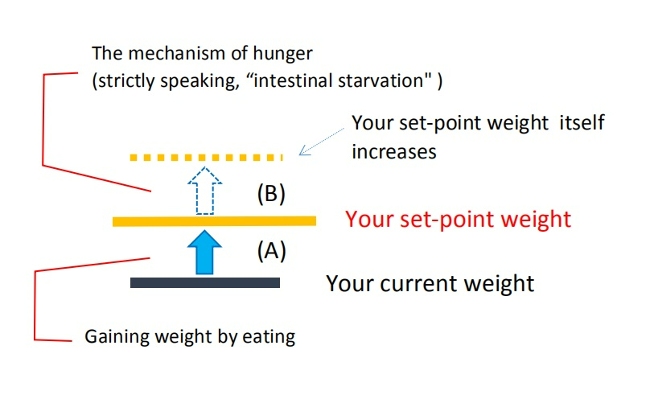

- When your weight goes back to your set-point weight (A)

- When your set-point weight itself increases (B)

Please check out my blog below before reading this one.

→ A Set-Point Weight; The Precondition Regarding the Rebound Effect

I would like to define this term first. There are two meanings of the expression "gaining weight" which we use daily. I think the confusion of these meanings causes a lot of misunderstandings.

For example, “you'll gain weight if you eat a lot of calories” or "despite dieting and eating less, you gain even more weight when you rebound,” etc.

I realized this when I got really thin, but I think the confusion of these two meanings results in various misunderstandings and false information, and most people are dieting in the wrong way.

1. When your weight goes back to your set-point weight (A)

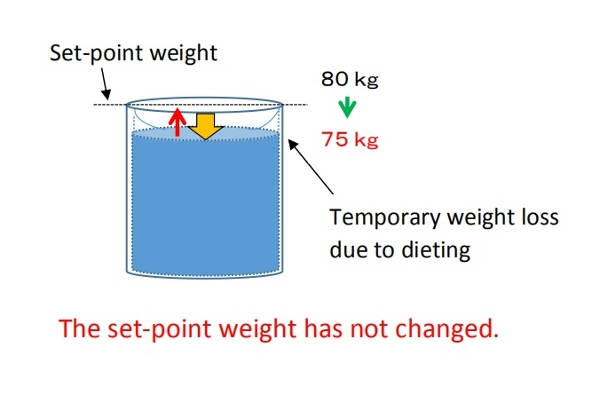

The first one is “gaining weight” meaning to go back to your set-point weight based on the mechanism of maintaining your present condition.

Many of those who are overweight try to keep their weight low by reducing their daily caloric intake and/or doing some exercise, because they do not want to gain weight.

In such cases, the body always tries to go back to its set-point. Therefore, it is no surprise that if they stop calorie restriction and return to their previous eating habits, they will gain weight.

(Note: Temporary overeating may cause a slight increase in weight beyond the set-point, but the set-point itself remains unchanged, and the weight gain can be considered temporary.)

When people say, "If I eat high-calorie foods, I gain weight easily," or "If I eat sweets or cake, I gain weight," they are mostly talking about this meaning.

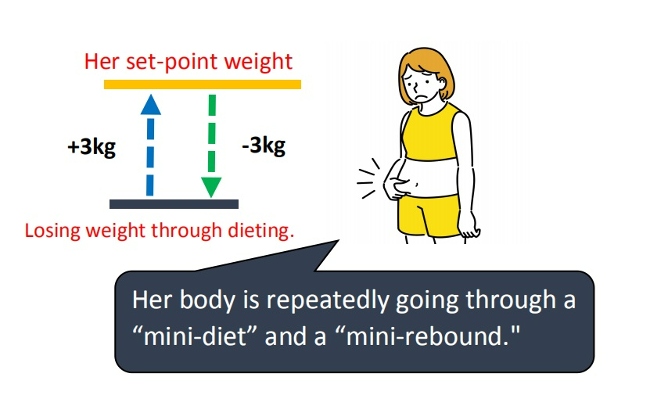

Sometimes I hear women say, "I have a body type that gains weight easily as soon as I eat a little more."

But, in my opinion, it means that the body is repeatedly going through a “mini-diet” and a “mini-rebound” by the mechanism to preserve its current stasis.

▷Toru Watanabe, a Japanese actor, used to be heavy, but with a diet, he weighed around 70kg when he appeared on a television show.

However, when he got married at twenty-six, he couldn't maintain his diet anymore and ate a lot and he went back to 130kg. (It is said that he made a new record for his weight change every time he dieted.)

Again with the help of his wife’s home cooking, he succeeded in losing 40kg.

However, in the end, he repeated rebounding. It’s quite a famous story in Japan.

(You can imagine a glass in which water is increasing and decreasing.)

2. When your set-point weight itself increases (B)

On the other hand, the second “gaining weight” expression means that your set-point weight itself increases.

Though I have reduced the amount of my food intake, I shattered my previous weight level and gained three kilograms in the last year which means I’ve gained ten kilograms in the last three years... meaning my maximum weight has increased.

This is not due to the amount of food eaten or caloric intake, but by the mechanism of hunger (strictly speaking, I have defined it as “intestinal starvation” ).

I believe that this makes a fundamental difference between fat people and thin/lean people. (You can imagine a glass of water that the glass itself is growing larger.)

[Related article]

My Definition of “Intestinal Starvation”

For example, someone who has never been more than sixty kilograms has become sixty-three kilograms in the last year. In this case, it means that his/her set-point weight itself increased from sixty to sixty-three kilograms.

When you gain weight to your set-point weight from a rebound after a diet, it's the (A) mechanism, but if you gain weight naturally more than your set-point weight, it is the (B) mechanism. This is because a calorie-restricted diet can create a situation of intestinal starvation.

It is generally believed in Japan that eating when your metabolism is slowing down makes you gain more weight, but it has already been proven that fat people have a higher basal metabolism[1].

■Japanese Sumo wrestlers are famous for eating a lot of rice and being fat, but I believe that, to put it in extreme terms, they will gain weight because of a mix of (A) and (B).

Although it looks like they eat more and are gaining weight, the mechanism should be the same as that of people who try dieting, but in the end, they gain more weight than before due to the rebound effect.

References:

[1] Dr. Jason Fung, The Obesity Code, 2016, Pages 62.

03/03/2016

The Set-Point Weight; The Precondition Regarding the Rebound Effect

-

Contents

-

- Each person has the ability to maintain their present condition

- Encounter with the set-point theory

1. Each person has the ability to maintain their present condition

First of all, I want to explain the most important point. It's the assumption that each person has the ability to maintain their present condition, also known as preserving current stasis in the body.

I recognize that this is the precondition of everyone regarding weight control.

For example, there are three women:

(A) 48kg・・・who can't gain weight even if she eats a lot.

(B) 58kg・・・who can easily gain two kilos if she lets her guard down and eats a little more.

(C) 85kg・・・ 〃

All through the year, we get thinner when we are busy, and we gain a little fat when we aren’t active and eat a lot. Although everyone repeats the same pattern, even if we don't calculate calories strictly, the body shape of person won't change so easily. Fat people are fat and thin people are thin.

In other words, I believe that each person has a stable weight based on their body's homeostatic functions, which I initially defined as their "base weight."

[Base weight] = The stable weight one returns to after spending 3-5 days relaxing without excessive exercise or work, while consuming calories based on their daily energy needs.

However, despite the lack of official proof or definition, some researchers have already used the concepts of 'set-point weight.' Additionally, my "base weight" can be confused with "baseline weight," which is used in some studies. Therefore, I will use 'set-point weight' or ‘set-point’ for body weight going forward."

In this example, Person A's set-point weight is forty-eight kilograms. However, for Persons B and C, the weights they quickly revert to when they let their guard down and eat a lot—sixty kilograms and eighty-seven kilograms, respectively—can be considered their actual set-point weight. This means that their homeostatic functions are working to maintain those weights.

So, it’s difficult to assume a person’s body and weight condition only with caloric intake.

Consider the example above, that if A continues an intake of 100kcal over her recommended daily caloric intake every day for several months or years, the assumption is that it will accumulate into fat and she will eventually gain weight up to the eighty-kilogram level. This is wrong (She might gain weight but that is a different mechanism).

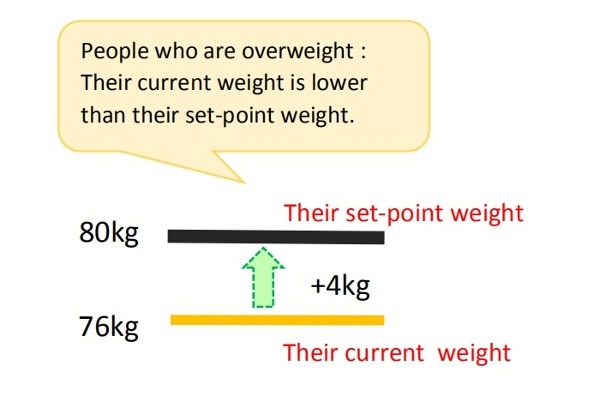

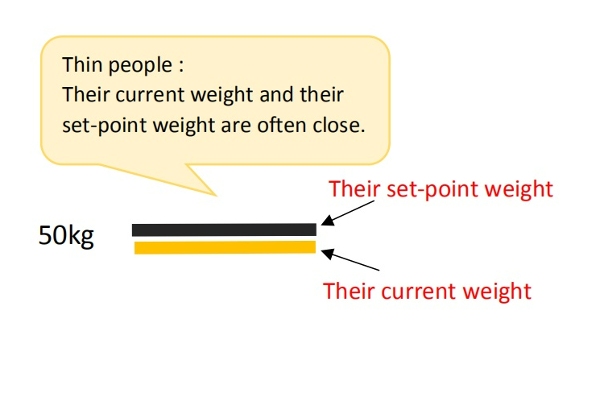

In general, people who are overweight are more likely to be restricting calories and eating modestly, so their current weight is often lower than their set-point weight. On the other hand, thin people don't have caloric restrictions, so their current weight and their set-point weight are often close. (Temporary overeating may lead to further weight gain beyond the body’s set-point, but I believe this weight gain is temporary and does not alter one’s set- point weight.)

Therefore, ‘thin A’ won't gain weight even if she eats a lot, and B and C will gain weight immediately as soon as they eat a lot.

▽Example of Hozumi Hasegawa, the professional boxer who defended his title ten times as the twenty-sixth Champion of WBC World bantamweight class.

The Bantamweight limit is fifty-three-point-five kilograms(53.5kg). As his body got older, losing weight became harder. For a defending match, he had to lose more than ten kilograms in a month.

But, as soon as the match was over and he started to eat, his weight increased ten kilograms in a few days. The rate of going back to his set-point weight was fast. Those who have tried diets and eat less than usual might have experienced this. Often, it's called the rebound effect.

2. Encounter with the set-point theory

Most of us do not consciously adjust our daily energy intake and expenditure. Nevertheless, an individual's body weight remains relatively stable.

Individual body weight variance is typically only 0.5% over periods of 6 to 10 weeks[1,2] (Khosha and Billewicz 1964). According to cross-sectional data, weight changes over longer periods of time are still modest, and even diabetic individuals display coefficients of body weight variation of only 3.7– 4.6% over a period of five years[1,3] (Goodner and Oglive 1974).

With the global increase in obesity since the 1970’s, these coefficients of body weight variation may no longer be as accurate. However, many people still stay lean (especially in Asia), and, in fact, even those who are overweight or obese manage to maintain their weight, heavy as they may be, for many years[4].

In other words, despite some fluctuations in weight in daily life, there must be an internal regulatory mechanism that works to keep weight and fat within a certain range over the long haul.

■In recent years, the role of homeostatic regulation has been acknowledged, and there is growing evidence that the body employs physiological mechanisms to control energy balance and maintain body weight at a genetically and environmentally determined "set-point."[5]

When a person loses weight, the body substantially lowers energy expenditure, often more than expected based on changes in body composition or the thermic effect of food.

Additionally, it triggers hormonal changes that increase appetite and modifies food preferences through behavioral adaptations, aiming to restore body weight to its set-point range[6].

This feedback mechanism is known to apply not only to weight loss but also to temporary overeating[7].

When I started writing this blog, I had no knowledge of the theory about the body's "set-point," but it almost aligned with what I had always believed. I now believe that understanding the set-point theory is crucial in preventing the spread of obesity and proposing effective weight loss methods.

In particular, to explain the global rise in obesity since the 1970’s, I believe it is essential to understand how (I) genetic and biological factors, and (II) environmental and behavioral factors combine to increase the body’s set-point for weight. I believe my intestinal starvation theory can contribute to this understanding.

For more details, please refer to the articles below.

[Related article]

The Increasingly Important "Set-Point" Theory of Body Weight

References:

[1]Richard E. Keesey, Matt D. Hirvonen. Body Weight Set-Points: Determination and Adjustment. The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 127, Issue 9, 1997, Pages 1875S-1883S, ISSN 0022-3166.

[2]KHOSLA T, BILLEWICZ WZ. MEASUREMENT OF CHANGE IN BODY-WEIGHT. Br J Nutr. 1964;18:227-39.

[3]Goodner CJ, Ogilvie JT. Homeostasis of body weight in a diabetes clinic population. Diabetes 1974 Apr;23(4):318-26.

[4] Gary Taubes. 2011. Why we get fat. New York: Anchor books, Page 59.

[5]Egan AM, Collins AL. Dynamic changes in energy expenditure in response to underfeeding: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2022 May;81(2):199-212. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121003669. Epub 2021 Oct 4. PMID: 35103583.

[6]Ganipisetti VM, Bollimunta P. Obesity and Set-Point Theory. 2023 Apr 25. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 37276312.

[7]Bray GA.The pain of weight gain: self-experimentation with overfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020 Jan 1;111(1):17-20.

- «

- 8 / 8