Topics

05/30/2018

Why Do We Gain Weight even Though We Eat Small Portions of Food?

Contents

- A woman friend who eventually put on some weight

- A colleague who gained three kilograms in a year

- "Just reduce calories" is a mistake

It is said that the cause of weight gain is the caloric intake exceeding calories burned through metabolism and activity. For this reason, I see people dieting by only reducing the amount of food they eat, and putting up with being hungry over long hours.

For example, they eat only a rice ball and a piece of fried chicken, or a hamburger and a drink for lunch. These people say they are hungry but continue experiencing hunger for long periods of time.

In my opinion, people like this not only do not diet well, but they also tend to gain weight eventually.

1. A woman friend who eventually put on some weight

When I was working part-time at a restaurant in college, there was a woman who wasn’t that overweight, but she started dieting anyway.

She wasn’t slim, but she wasn’t overweight, either. To me, she looked healthy and fit. I thought she was okay as she was. But it seemed that she started dieting because she wanted to get slim.

Therefore, she only ate half of her meal, such as rice and meat/fish dish and never any vegetables. She was always saying, “I’m starving...” but continued experiencing hunger and stopped eating snacks.

As a result, not only did she not lose weight, but she also gained a little weight.

2. A colleague who gained three kilograms in a year

The same goes for my colleague, T, who worked as a cook in the kitchen at a nursing home. When I first met him, he was a stocky guy (about 170cm tall and 70 kilos).

He wasn’t overweight but he was on a diet, saying he had gained three kilos which shattered his previous weight level in the last year.

In his case, he was working before six a.m., but he hardly ever ate breakfast.

For lunch, he only ate a small bowl of rice and meat or fish. He almost never ate vegetable dishes such as salad and simmered vegetables (traditional Japanese vegetable stew).

He gained two more kilos in the following year.

3. "Just reduce calories" is a mistake

What's wrong with this is, that the people previously mentioned thought that in order to lose weight, they only needed to reduce calories from carbohydrates, meat, and fat, etc. Furthermore, they thought they had to be hungry in order to lose weight.

As a result, I can posit that intestinal starvation was induced because they didn’t consume fiber from vegetables, fat, and dairy products, etc. very much, causing the set-point weight to increase.

There are two ways in which the intestinal starvation mechanism occurs.

(1) Eating regular or big portions of an unbalanced meal, but not eating as often (e.g. skipping breakfast and eating two meals a day) and experiencing hunger over many hours.

(2)Eating small portions as seen in dieters or pregnant women, sometimes skewed towards digestible carbohydrates and protein, etc. Even if they eat three times a day, they often experience hunger over many hours.

In conclusion, whether you eat a good amount of food or a small portion of food, if your diet consists of mostly digestible carbs and some protein, an imbalance of food in the intestines remains the same. If you don’t eat anything else and experience hunger over many hours, it leads to the similar effect in view of creating intestinal starvation.

Eating vegetable dishes, dairy products and fat/oil, etc. is important with regards to preventing intestinal starvation, but those people in the previous examples were only conscious of caloric intake, and chose not to eat them.

05/29/2018

Misunderstanding of the Relationship Between Diet, Exercise, and Body Weight

-

Contents

-

<Introduction>

- The relationship between “diet and exercise” is the most commonly used excuse

- Expended energy will be regained

- What does “diet is the priority” mean?

<The bottom line>

<Introduction>

The fact that many people who play sports are lean, and that we see athletes who have gained a lot of weight after retiring from active sports, seems to make the formula "exercise = losing weight" true.

Most experts see it this way, but the relationship between exercise and weight should not be as simple as this.

This time, I’d like to explain the relationship between "diet, exercise, and body weight" based on my theory.

1. The relationship between “diet and exercise” is the most commonly used excuse, for specialists

First of all, for those who have not lost weight even after exercising, physicians and specialists would say, "After all, you must be eating a lot somewhere," and for those who have not lost weight even after restricting calories, they would say, "You are not exercising enough, are you?"

That is to say, the relationship between diet and exercise has been regarded as a "calories-in/calories-out" relationship, which has been used as an excuse by experts, and the relationship has not even been considered in an in-depth manner.

2. Expended energy will be regained

First, some people think in terms like "overeating always leads to weight gain" or "exercise causes weight loss," as shown in Figure-1.

<Figure-1>

They believe that "intake and expenditure are are opposites, and we will gain or lose weight depends on the balance between the two.”

However, in reality, it should be more like Figure-2.

<Figure-2>

Since the food we consume and the energy used in our bodies are mediated by absorption, an increase in energy expenditure will increase absorption rate, which in turn increase one’s appetite through hormonal changes.

In contrast, if we increase the amount and frequency of eating when we are at rest and not hungry, the absorption rate will decrease.

Exercise certainly consumes more energy, but a counter-regulatory function-that the body tries to regain energy that it has expended-should work.

In other words, exercise is essentially a force that pushes the body in the direction of gaining strength and ultimately, storing energy (weight gain) as it tries to stimulate energy circulation and re-energize the body. (In particular, it works more strongly in resistant exercises that target muscles.)

However, whether or not you gain weight depends on how you control the way you eat.

“Diet” is always the priority.

This is why false theories emerge like, “people exercising everyday are lean no matter how much they eat.”

3. What does “diet is the priority” mean?

The simple explanation is that even though exercise ultimately pushes the body to store energy, if some undigested food is always left in the intestines, as a result, intestinal starvation does not occur and the set-point weight remains the same.

I will explain this in greater detail several ways.

(1) Not gaining weight while exercising regularly

As Dr. Briffa, the author of “Escape the Diet Trap,” says in his book, it is better to think that, "originally lean people start running marathons or playing soccer, and eventually become athletes[1].” It may be a cynical view, but I think it’s probably correct.

They know they never gain weight even though they eat a lot, and most athletes eat three well-balanced meals, plus other nutritional supplements and snacks.

(Traditional Japanese breakfast)

This is because when we try to exercise, our mindset is that we need to be nourished and that we need to eat well.

In other words, when naturally lean people take up sports like soccer or marathon running and eat three balanced meals a day, the intestinal starvation mechanism is less likely to be induced, allowing them to maintain the same weight over many years.

(2) Putting on some weight after quitting exercise

On the other hand, there might be people who have gained 3–4 kg over the past few years because their work involves desk tasks or light physical activity, and they haven’t exercised recently.

However, the real issue, I believe, is not the lack of exercise, but rather skipping meals, eating light meals, having an unbalanced diet relying too much on carbohydrates, or irregular eating habits.

When we have nothing to do or do light physical work all day, we tend to think that we need to eat less and become less concerned about nutritional balance, don't we?

Perhaps some people might go to work without breakfast, or just have a simple lunch such as ramen noodles, a sandwich, or a hamburger.

In this case, the body's ability to take in nutrients is low compared to during exercise, but on the contrary, if you spend long periods hungry, intestinal starvation is more likely to occur, which may ultimately increase your set-point weight over time.

Additionally, when athletes retire, their caloric expenditure decreases and opportunities to eat often increase, which can lead to a few kilograms of weight gain. I see this as the same mechanism that causes weight to rebound after dieting, where the body returns to its set-point weight.

However, if there is a weight gain of more than ten kilograms over a few years, this is likely due more to changes in eating habits, as explained above, and can be attributed to weight gain caused by intestinal starvation.

(3) Gaining weight while exercising

Fighters and sumo wrestlers exercise, of course, but due to the nature of their sports, they sometimes need to increase their muscle mass or body weight. However, we often hear that it’s not easy for some fighters to gain muscle mass and weight even if they eat protein supplements in addition to their three meals.

On the other hand, those who don’t want to gain weight sometimes put on weight quite effortlessly. This is because, as I have mentioned so many times, gaining weight (meaning an increase in one’s set-point weight) requires the induction of intestinal starvation.

During high-intensity strength exercises, like barbell exercises, the body’s regulatory mechanism to restore lost energy is even more powerful than with aerobic exercise.

However, if one tries to consume more calories and nutrients every 4 to 5 hours through meals or protein supplements, some undigested food tends to remain in the intestines throughout the day, which could ultimately hinder an increase in set-point weight.

<A sumo wrestler's diet: a practical approach to increasing body weight>

Sumo wrestlers in Japan are famous for being large and heavy, but they traditionally eat only twice a day, instead of three times a day.

Moreover, their meals are not greasy foods but mainly consist of easily digestible hot-pot dishes called “chanko” (a stew with chicken meat and vegetables, etc.) along with plenty of rice.

Therefore, the food they eat can be more easily digested, and when intestinal starvation is triggered, it can lead to weight gain, suggesting an increase in their set-point weight.

■For details on how weight is increased when intestinal starvation is induced, please refer to the article below.

[Related article]

Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

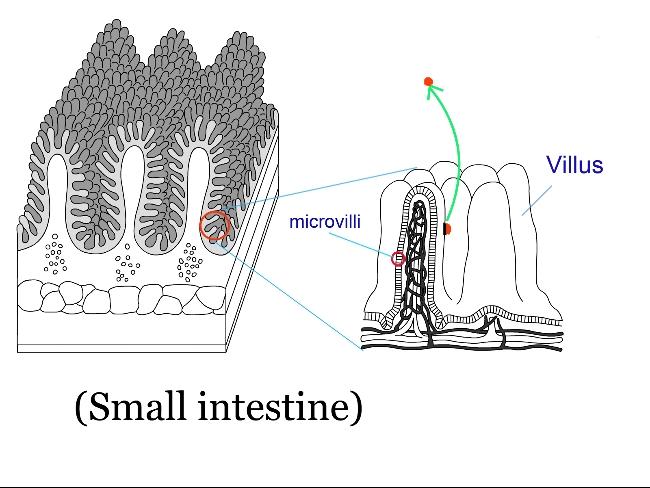

In simple terms, I believe that when all food is fully digested, microscopic substances attached to the villi (or microvilli) of the small intestine detach themselves, which expands the surface area for absorption and boosts absolute absorption capacity.

Resistance exercises that target muscles (particularly lifting) accelerate this mechanism beyond its usual rate.

In other words, the diet and exercise of sumo wrestlers provide a logical approach to increasing muscle mass and body weight.

The bottom line

(1)The relationship between diet and exercise is not simply an energy "in/out" relationship.

Exercise is essentially a force that works toward gaining strength and weight because the opposite reaction-that the body tries to regain energy that it has expended-should work (especially in the case of high-intensity exercise).

(2) However, the priority is in how we control our diet. Eating three well-balanced meals every day will help undigested food to remain in the intestines, and the set-point weight is less likely to increase.

People who are originally lean start athletics, soccer, etc., and if they eat three well-balanced meals every day, they are less likely to gain weight and maintain the same body shape over the years.

(3) People tend to skip meals or eat less when they aren’t exercising or are only doing light physical work. In such cases, the body's regulatory function to absorb nutrients and store fat are weaker than during exercise, but in contrast, people end up feeling hungrier and intestinal starvation is more likely to be caused, resulting in an increase in one's set-point weight.

(4)The way sumo wrestlers eat and exercise is a logical approach to increasing muscle strength and body weight. By eating digestible meals including a good amount of rice twice a day, they are more likely to induce intestinal starvation. Intense training further accelerates this effect.

References:

[1] Jone Briffa. Escape the Diet Trap. London: Fourth Estate, 2013, Page 223.

02/01/2018

For Dieting, Meal Improvement Rather than Exercise

Contents

- Little benefit of expended calories

- Improving diet is more important

(1) Deceived by hype

(2) When proposing exercise, always provide meal coaching, too

<The bottom line>

Please read “Is Exercise Really Necessary to Lose Weight?,” first.

In the above article, we considered how exercise can really help people lose weight, but let's explore that in more detail.

1. Little benefit of expended calories

"A 250-pound man will burn three extra calories (kcal)climbing one flight of stairs, as Louis Newburgh of the University of Michigan calculated in 1942.

“He will have to climb twenty flights of stairs to rid himself of the energy contained in one slice of bread!”

So why not skip the stairs and skip the bread and call it a day?

After all, what are the chances that if a 250-pounder does climb twenty extra flights a day he won't eat the equivalent of an extra slice of bread before the day is done?"

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why We Get Fat. Page 48.)

"Other experts took to arguing that we could lose weight by weightlifting or resistance training rather than the kind of aerobic activity, like running, that was aimed purely at increasing our expenditure of calories.

The idea here was that we could build muscle and lose fat, and so we'd be fitter even if our weight remained constant, because of the trade-off. Then the extra muscle would contribute to maintaining the fat loss, because it would burn off more calories—muscle being more metabolically active than fat.

To make this argument, though, these experts invariably ignored the actual numbers, because they, too, are unimpressive.

If we replace five pounds of fat with five pounds of muscle, which is a significant achievement for most adults, we will increase our energy expenditure by two dozen calories(kcal) a day.

Once again, we're talking about the caloric equivalent of a quarter-slice of bread, with no guarantee that we won't be two-dozen-calories-a-day hungrier because of this.

And once again we're back to the notion that it might be easier just to skip both the bread and the weightlifting."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 54-5.)

2. Improving diet is more important

Walking, jogging, and other forms of exercise are undoubtedly necessary for the prevention of chronic diseases, and for mental and physical health, but as we reviewed in detail in section[1] above, they are not that effective in terms of caloric expenditure.

I suspect that those who say that they have lost weight through exercise are doing so through a set of dietary improvements (such as balanced diet and how often they eat, etc.).

There is a book written by a Japanese exercise specialist, Takuro Mori, on this subject, and I would like to dive deeply into this:“Sports coach declares. For dieting, exercise should be ten percent and meals should be ninety percent”

Mr. Mori worked in a fitness club for five years, and though he is a sports coach, he says it’s impossible to lose weight only with exercise.

(1) Deceived by hype

“As an exercise instructor, I’ve seen hundreds and thousands of clients. However, what I saw there were long-time club members who had not gotten slim, and moreover, some staff who had not lost weight despite the fact that they worked as coaches in a sports club.(*snip*)

The key to successful dieting is mostly the improvement of diet and the mentality to support it.

As for exercise, I believe that it is very small in comparison to those two factors, and if we can manage to improve diet and mentality, we can get mostly good results, even if we omit the exercise guidance.

It is also true that I was deceived by various diet-related hype and believed, unknowingly, that anyone could lose weight with effective exercise....(omitted)

That is just an advertisement, so it is natural that it is an exaggeration to attract customers. Because of that, it’s manipulating people’s general perception.”

(2)When proposing exercise, always provide meal coaching, too

“Through my past exercise and diet coaching, I have become acutely aware that most people actually do not achieve results with only exercise. As I interacted with many clients, I began to see a trend in those who failed to achieve results.

They all had problems in their eating habits such as they kept eating what they liked or didn’t want to change their eating habit.

Considering the body's mechanism for losing weight, there is no more effective way to lose weight than by controlling diet, and the appropriate approach is to add the necessary amount of exercise to it.

If you pick up any diet book on the street, you will find that most of them refer to diet, even if they explain a particular exercise regimen.

Successful dieters lose weight by improving their diet (eating a balanced diet and eating more often, etc.), not by exercising. (*snip*)

It is necessary to understand the basic premise that exercise creates a beautiful body style, and if you want to lose weight and size, you must improve your diet and other aspects of your life.[1]"

This is what I wanted to tell you, but I had to quote an exercise expert because he is more convincing.

Diet books that claim, "you can lose weight with exercise," always mention improving your diet.

The trend these days seems to be changing to eating fewer carbohydrates, and eating more protein (meat, eggs, etc.), vegetables, dairy products, etc., while exercising.

You might think that exercise has contributed significantly to your weight loss since you lost weight by eating enough, but you would be mistaken.

It may be better to think that changing your eating habits can actually help you reduce weight and size, and that exercise is more about building a lean, toned body while you lose weight.

The bottom line

(1) Calories burned in exercise are not that many . Those who exercise but do not get results from dieting often have some problem with their eating habits, such as wanting to lose weight while eating what they like.

(2) To lose weight, it is more effective to review one's daily eating habits. Reducing carbohydrate intake to some extent and increasing protein, fat, dairy products, and vegetables can be helpful.

On the other hand, exercise helps to improve overall health, maintain muscle strength, and build a toned body.

(3) The reason exercise is not fundamentally helpful for weight loss is because the relationship between diet, exercise, and weight is misunderstood.

[Related article] Misunderstanding of the Relationship Between Diet, Exercise and Body Weight

References:

[1]Takuro Mori. For dieting, exercise should be ten percent and meal should be ninety percent (森 拓郎,「ダイエットは運動1割、食事9割」). 2013.

01/31/2018

Is Exercise Really Necessary to Lose Weight?

Contents

- Exercise is good for your health, but what about losing weight?

- Some reasons to doubt the weight-loss benefits of exercise

- Energy expenditure and intake are closely linked

- Evidence that exercise has no effect on weight loss was ignored

<The bottom line>

Prologue

"Imagine you're invited to a celebratory dinner.

The chef's talent is legendary, and the invitation says that this particular dinner is going to be a feast of monumental proportions. Bring your appetite, you're told—come hungry.

How would you do it?

You might try to eat less over the course of the day,—maybe even skip lunch, or breakfast and lunch. You might go to the gym for a particularly vigorous workout, or go for a longer run or swim than usual, to work up an appetite. You might even decide to walk to the dinner, rather than drive, for the same reason.

Now let's think about this for a moment. The instructions that we're constantly being given to lose weight–eat less and exercise more —are the very same things we'll do if our purpose is to make ourselves hungry, to build up an appetite, to eat more.

Now the existence of an obesity epidemic coincident with half a century of advice to eat less and exercise more begins to look less paradoxical."

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why We Get Fat. Page 40.)

1. Exercise is good for your health, but what about losing weight?

“It's now commonly believed that sedentary behavior is as much a cause of our weight problems as how much we eat. And because the likelihood that we'll get heart disease, diabetes, and cancer increases the fatter we become, the supposedly sedentary nature of our lives is now considered a causal factor in these diseases as well.

Regular exercise is now seen as an essential means of prevention for all the chronic ailments of our day.

(*snip*)Faith in the health benefit of physical activity is now so deeply ingrained in our consciousness that it's often considered the one fact in the controversial science of health and lifestyle that must never be questioned.(*snip*)

But the question I want to explore here is not whether exercise is fun or good for us or a necessary adjunct of a healthy lifestyle, as the authorities are constantly telling us, but whether it will help us maintain our weight if we're lean, or lose weight if we're not.

The answer appears to be no. (*snip*)

The ubiquitous faith in the belief that the more calories we expend, the less we’ll weigh is based ultimately on one observation and one assumption.

The observation is that people who are lean tend to be more physically active than those of us who aren't. This is undisputed. Marathon runners as a rule are not overweight or obese.

But this observation tells us nothing about whether runners would be fatter if they didn't run or if the pursuit of distance running as a full-time hobby will turn a fat man or Woman into a lean marathoner."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 41, 46.)

2. Some reasons to doubt the weight-loss benefits of exercise

In the following article, I believe I mentioned that adding exercise to a conventional calorie-restricted diet has not been very effective, and I will try to explore why. I would like to address the following five points.

【Related article】 Dieting Doesn’t Work in the Long Run

(I)Overweight among the poor

"In the United States, Europe, and other developed nations, the poorer people are, the fatter they're likely to be. It's also true that the poorer we are, the more likely we are to work at physically demanding occupations, to earn our living with our bodies rather than our brains. (*snip*)

They may not belong to health clubs or spend their leisure time training for their next marathon, but they're far more likely than those more affluent to work in the fields and in factories, as domestics and gardeners, in the mines and on construction sites.

That the poorer we are the fatter we're likely to be is one very good reason to doubt the assertion that the amount of energy we expend on a day-to-day basis has any relation to whether we get fat.

If factory workers can be obese, as I discussed earlier, and oil-field laborers, it's hard to imagine that the day-to-day expenditure of energy makes much of a difference. "

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 41-2.)

(II) Exercise makes you hungrier

Many people have probably realized that exercise and manual labor will make them feel "hungrier" and have a greater appetite than in a sedentary life such as a desk job. Some of you may have exercised to lose weight, but ended up eating chocolate or other sweets because you were tired and then regretted your own weak will and "lack of self-control.”

(III) Increased absorption rate

The effect of aerobic or anaerobic exercise on body fat loss is said to be different, but either way, I believe the energy once expended through exercise will basically come back.

When we exercise, our muscles need energy. Depending on the intensity of the exercise, energy is produced mainly from blood glucose, muscle glycogen, and fatty acids from fat cells. Of course, energy expenditure will increase once, but then I believe the body will increase its absorption rate to absorb more nutrients from food in the intestines to compensate for those lost nutrients.

“Increased absorption rate” might be difficult to understand but think of it this way: When a person drinks alcohol on an empty stomach or drinks alcohol after exercising, it will make them more intoxicated or a person turns redder than usual (AKA the Asian glow).

And, if you are not a drinker, eating or drinking something sweet after exercise may cause your blood sugar to rise more rapidly than usual.

(IV) Become less active at other times

It is said that when people increase their amount of exercise, they naturally tend to become inactive the rest of their lives.

For example, after completing a thirty-minute jog, one may end up relaxing on the couch for a couple of hours because of the fatigue, or may become less active than usual over the course of the day.[1]

(V)Small amount of body fat burned

Body fat is a stored form of energy, so it is not used immediately. Therefore, in the case of high-intensity anaerobic exercise that stresses the muscles, ATP and creatine phosphate stored in the muscles are used as an energy source for about 15 seconds from the start. After that, what is being expended is blood glucose and glycogen, the fast-acting energy source stored in the muscles.

In aerobic exercise such as jogging, which is said to burn more body fat, there is a concept of a fat-burning zone (low-intensity exercise that keeps your heart rate between 60 and 69 percent of maximum heart rate), but even in this case, about fifty percent of the calories burned come from fat.[2].

Even if the calories burned in thirty minutes of jogging are two hundred kcal, that does not all translate into a reduction in body fat.

3. Energy expenditure and intake are closely linked

In section [2] above, I explained about increased absorption rate, having a bigger appetite, and becoming inactive after exercise, but I will quote again from "Why We Get Fat" for a more scientific explanation.

"The very notion that expending more energy than we take in-eating less and exercising more-can cure us of our weight problem, make us permanently leaner and lighter, is based on yet another assumption about the laws of thermodynamics that happens to be incorrect.

The assumption is that the energy we consume and the energy we expend have little influence on each other, that we can consciously change one and it will have no consequence on the other, and vice versa. (*snip*)

Intuitively we know this isn't true, and the research in both animals and humans, going back a century, confirms it. People who semi-starve themselves, or who are semi-starved during wars, famines, or scientific experiments, are not only hungry all the time but lethargic, and they expend less energy. And increasing physical activity does increase hunger; exercise does work up an appetite. (*snip*)

In short, the energy we consume and the energy we expend are dependent on each other. Mathematicians would say they are dependent variables, not independent variables, as they have typically been treated. Change one, and the other changes to compensate. (*snip*)

Anyone who argues differently is treating an extraordinarily complex living organism as though it were a simple mechanical device. (*snip*)

In 2007, Jeffrey Flier, dean of Harvard Medical School and his wife and colleague in obesity research, Terry Maratos-Flier, published an article in Scientific American called “What Fuels Fat.”

In it, they described the intimate link between appetite and energy expenditure, making clear that they are not simply variables that an individual can consciously decide to change with the only effect being that his or her fat tissue will get smaller or larger to compensate. "

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 77-8.)

4. Evidence that exercise has no effect on weight loss was ignored

"As it turns out, very little evidence exists to support the belief that the number of calories we expend has any effect on how fat we are.

In August 2007, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) addressed this evidence in a particularly damning manner when they published joint guidelines on physical activity and health. (*snip*) Thirty minutes of moderately vigorous physical activity, they said, five days a week, was necessary to “maintain and promote health.”

But when it came to the question of how exercising affects our getting fat or staying lean, these experts could only say: “It is reasonable to assume that persons with relatively high daily energy expenditures would be less likely to gain weight over time, compared with those who have low energy expenditures. So far, data to support this hypothesis are not particularly compelling." (*snip*)

From the late 1970s onward, the primary factor fueling the belief that we can maintain or lose weight through exercise seemed to be the researchers' desire to believe it was true and their reluctance to acknowledge otherwise publicly.

Although one couldn't help being “underwhelmed” by the actual evidence, as Judith Stern, Mayer's former student, wrote in 1986, it would be “shortsighted” to say that exercise was ineffective, because it meant ignoring the possible contributions of exercise to the prevention of obesity and to the maintenance of any weight loss that might have been induced by diet. (*snip*)

As for the researchers themselves, they invariably found a way to write their articles and reviews that allowed them to continue to promote exercise and physical activity, regardless of what the evidence actually showed.

One common method was (and still is) to discuss only the results that seem to support the belief that physical activity and energy expenditure can determine how fat we are, while simply ignoring the evidence that refutes the notion, even if the latter is in much more plentiful supply."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 43-4, 53-4.)

The bottom line

(1) The idea that the more calories we burn, the lighter we weigh is based on the observation that "lean people tend to be physically more active than those who are not." However, there is little evidence to support this.

(2) Everyone would probably agree that "lean people tend to be more physically active than those who are not." However, it is not as simple as, "if you increase caloric expenditure through exercise, you will lose weight.” The relationship between exercise and weight is more complex.

【See more】Misunderstanding of the Relationship Between Diet, Exercise and Body Weight

(3) Calories consumed and calories expended are interconnected, and if you exercise more, you will feel hungrier and have a bigger appetite. Even if you keep your caloric intake the same, your body will try to regain lost energy source and nutrients due to increased absorption rate after exercise.

(4) The problem with being overweight is that one's set-point for body weight is elevated, and while energy expenditure through exercise may lead to temporary weight loss, it is not effective in the long run.

As we’ll see in more detail in the following blogs, it is more important to improve dietary balance and intake methods (when or how often you eat, etc.) in combination with exercise.

【Related article】 For Dieting, Meal Improvement Rather than Exercise

References:

[1]Dr. John Briffa. Escape the Diet Trap. London: Fourth Estate, 2013, Page 222.

[2]University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program.「Fuel Sources for Exercise」. 2018.

12/10/2017

Wealthy People Get Fat? Poor People Get Fat?

-

Contents

-

- Wealth is said to be the cause of obesity....

- The case of poverty and obesity

- Why were they fat?

- Though we have become wealthy, how is the quality of our food? My thoughts

I would like to share with you an interesting story based on profound research that is also relevant to my theory. I will conclude this post with my thoughts.

【Related article】The Combination of Thin and Overweight in the Same Poor Group Is Not Contradictory

1. Some believe that wealth is said to be the cause of obesity...

"Ever since researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) broke the news in the mid-1990s that the epidemic was upon us, authorities have blamed it on overeating and sedentary behavior and blamed those two factors on the relative wealth of modern societies.

■'Improved prosperity' caused the epidemic, aided and abetted by the food and entertainment industries, as the New York University nutritionist Marion Nestle explained in the journal Science in 2003.

'They turn people with expendable income into consumers of aggressively marketed foods that are high in energy but low in nutritional value, and of cars, television sets, and computers that promote sedentary behavior. Gaining weight is good for business.'

■The Yale University psychologist Kelly Brownell coined the term 'toxic environment' to describe the same notion.

Just as the residents of Love Canal or Chernobyl lived in toxic environments that encouraged cancer growth, the rest of us, Brownell says, live in a toxic environment 'that encourages overeating and physical inactivity.'

'Cheeseburgers and French fries, drive-in windows and supersizes, soft drinks and candy, potato chips and cheese curls, once unusual, are as much our background as tree, grass, and clouds. Computers, video games, and televisions keep children inside and inactive,' he says.(*snip*)

▽The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the identical logic to explain the obesity epidemic worldwide, blaming it on rising incomes, urbanization, 'shifts toward less physically demanding work...moves toward less physical activity...and more passive leisure pursuits.'

Obesity researchers now use a quasi-scientific term to describe exactly this condition: they refer to the 'obesigenic' environment in which we now live, meaning an environment that is prone to turning lean people into fat ones."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 17-8.)

In Japan as well, this idea is widely accepted, and most experts on television explain that overeating and physical inactivity are the causes of obesity.

2. The case of poverty and obesity

However, what we have to consider here is that obesity is spreading in the poor layers of society, too.

"One piece of evidence that needs to be considered in this context, however, is the well-documented fact that being fat is associated with poverty, not prosperity-certainly in women, and often in men. The poorer we are, the fatter we're likely to be. (*snip*)

In the early 1970s, nutritionists and research-minded physicians would discuss the observations of high levels of obesity in these poor populations, and they would occasionally do so with an open mind as to the cause.(*snip*)

This was a time when obesity was still considered a problem of 'malnutrition' rather than 'overnutrition,' as it is today."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 18, 29.)

"Between 1901 and 1905, two anthropologists independently studied the Pima (Native American tribe in Arizona), and both commented on how fat they were, particularly the women.

Through the 1850s, the Pima had been extraordinarily successful hunters and farmers. By the 1870s, the Pima, however, were living through what they called the 'years of famine.' (*snip*)

When two anthropologists (Russell and Hrdlička) appeared, in the first years of the twentieth century, the tribe was still raising what crops it could but was now relying on government rations for day-to-day sustenance.

What makes this observation so remarkable is that the Pima, at the time, had just gone from being among the most affluent Native American tribes to among the poorest.

Whatever made the Pima fat, prosperity and rising incomes had nothing to do with it; rather, the opposite seemed to be the case. (*snip*)

(A quarter-century after Russell and Hrdlička visited Pima)

Two researchers from the University of Chicago studied another Native American tribe, the Sioux living on the South Dakota Crow Creek Reservation.

These Sioux lived in shacks 'unfit for occupancy,' often four to eight family members per room. Many had no plumbing and no running water. Forty percent of the children lived in homes without any kind of toilets. Fifteen families, with thirty-two children among them, lived "chiefly on bread and coffee.' This was poverty almost beyond our imagination today.

Yet their obesity rates were not much different from what we have today in the midst of our epidemic : 40 percent of the adult women on the reservation, more than a quarter of the men, and 10 percent of the children, according to the University of Chicago report, 'would be termed distinctly fat.'"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 20-24.)

1950-1980’s

This combination of obesity and undernutrition existing in the same populations have been found and reported from around the world, including the West Indies, South Africa, Chile, Ghana, and Jamaica.

3. Why were they fat?

<About the case of Manhattanites, in the early 1960's>

"This was first reported in a survey of New Yorkers-midtown Manhattanites-in the early 1960s: obese women were six times more likely to be poor than rich; obese men, twice as likely. (*snip*)

Can it be possible that the obesity epidemic is caused by prosperity, so the richer we get, the fatter we get, and that obesity associates with poverty, so the poorer we are, the more likely we are to be fat?

It's not impossible. Maybe poor people don't have the peer pressure that rich people do to remain thin. Believe it or not, this has been one of the accepted explanations for this apparent paradox.

Another commonly accepted explanation for the association between obesity and poverty is that fatter women marry down in social class and so collect at the bottom rungs of the ladder; thinner women marry up.

A third is that poor people don't have the leisure time to exercise that rich people do; they don't have the money to join health clubs, and they live in neighborhoods without parks and sidewalks, so their kids don't have the opportunities to exercise and walk.

These explanations may be true, but they stretch the imagination, and the contradiction gets still more glaring the deeper we delve."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page18-19)

<About the case of the Pima (Native American tribe in Arizona >

"So why were they fat? Years of starvation are supposed to take weight off, not put it on or leave it on, as the case may be. And if the government rations were simply excessive, making the famines a thing of the past, then why would the Pima get fat on the abundant rations and not on the abundant food they'd had prior to the famines?

Hrdlička also thought that their physical inactivity was the cause of obesity because they were sedentary in comparison with what they used to be. This is what Hrdlička called 'the change from their past active life to the present state of not a little indolence.' But then he couldn't explain why the women were typically the fat ones, even though the women did virtually all the hard labor in the villages—harvesting the crops, grinding the grain, even carrying the heavy burdens.

▽Perhaps the answer lies in the type of food being consumed, a question of quality rather than quantity.

This is what Russell was suggesting when he wrote that 'certain articles of their food appear to be markedly flesh producing.'

The Pima were already eating everything 'that enters into the dietary of the white man,' as Hrdlička said. This might have been key.

The Pima diet in 1900 had characteristics very similar to the diets many of us are eating a century later, but not in quantity, in quality."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 22-3.)

4. Though we say we have become wealthy, how is the quality of our food? My thoughts

I want to explain my consideration based on numbers one to three.

First of all, when considering "obesity," isn't it too simplistic to think that obesity has increased since we have become wealthier?

It is true that our lives are wealthier than we used to be in terms of freedom of choice and an abundance of goods. If we have a certain income, we can do what we like and eat what we want.

However, when the income is low, we can’t spend a lot for food. Also, we don’t have enough time to eat, since many of us are so busy at work or with household chores.

We might eat an unbalanced diet leaning toward carbohydrates (and not enough vegetables) such as eating toast and coffee for breakfast, and a burger or a cup of noodles for lunch. We might skip breakfast or lunch.

In addition, those who gain weight easily try to eat a simple light meal or skip a meal, since they ate a lot the day before. The idea of offsetting an over-intake of calories from yesterday, eating less today, is wrong.

That is to say, even if someone is said to be wealthy, with regards to food, there are many things in common with groups that live in poverty with a high rate of obesity. As Mr. Taubes says, what is important now is the “quality” of food rather than the “quantity.”

In an extreme argument, obesity with poverty can be explained by the same mechanism that people who are on a diet end up gaining more weight after they stop dieting, even though they reduced the caloric intake.

"Not all of us get fat when we eat carbohydrates, but for those of us who do get fat, the carbohydrates are to blame; the fewer carbohydrates we eat, the leaner we will be.

(*snip*)

These foods are also, almost invariably, the cheapest calories available. This is the conspicuous explanation for why the poorer we are, the fatter we're likely to be"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 134-5.)