Topics

10/10/2022

Does Obesity Run in the Family or Is It Due to the Living Environment?

Contents

- What was the relationship of weight between adoptees and adoptive parents?

- What was the weight of the twins raised apart?

- What do we consider a change in environment?: My thoughts

- Will the shape of your body from childhood continue?

<The bottom line>

Is obesity inherited from parents?

Let us recall our classmates in elementary school. To some extent, we can imagine, if not one hundred percent, that if the parents are thin, their children are often thin, and if the parents are fat, their children are often fat.

The question here is whether this is due to genetics or due to the living environment. Here is one such study I’d like to introduce.

1. What was the relationship of weight between adoptees and adoptive parents?

"Obese children often have obese siblings. Obese children become obese adults. Obese adults go on to have obese children. Childhood obesity is associated with a 200 percent to 400 percent increased risk of adult obesity. This is an undeniable fact. (*snip*)

Families share genetic characteristics that may lead to obesity. However, obesity has become rampant only since the 1970s. Our genes could not have changed within such a short time. Genetics can explain much of the inter-individual risk of obesity, but not why entire populations become obese.

Nonetheless, families live in the same environment, eat similar foods at similar times and have similar attitudes. Families often share cars, live in the same physical space and will be exposed to the same chemicals that may cause obesity–so-called chemical obesogens. For these reasons, many consider the current environment the major cause of obesity.

Conventional calorie-based theories of obesity place the blame squarely on this “toxic" environment that encourages eating and discourages physical exertion. Dietary and lifestyle habits have changed considerably since the 1970s (e.g. car, television, computer, fast food, high-calorie food, sugar, etc.).

Therefore, most modern theories of obesity discount the importance of genetic factors, believing instead that consumption of excess calories leads to obesity. Eating and moving are voluntary behaviors, after all, with little genetic input.

So-exactly how much of a role does genetics play in human obesity?"

(Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Page 21-2.)

"The classic method for determining the relative impact of genetic versus environmental factors is to study adoptive families, thereby removing genetics from the equation.(*snip*)

Dr. Albert J. Stunkard performed some of the classic genetic studies of obesity. Data about biological parents is often incomplete, confidential and not easily accessible by researchers. Fortunately, Denmark has maintained a relatively complete registry of adoptions, with information on both sets of parents.

Studying a sample of 540 Danish adult adoptees, Dr. Stunkard compared them to both their adoptive and biological parents.

If environmental factors were most important, then adoptees should resemble their adoptive parents. If genetic factors were most important, the adoptees should resemble their biological parents.

No relationship whatsoever was discovered between the weight of the adoptive parents and the adoptees.(*snip*)

Comparing adoptees to their biological parents yielded a considerably different result. Here there was a strong, consistent correlation between their weights.

The biological parents had very little or nothing to do with raising these children, or teaching them nutritional values or attitudes toward exercise. Yet the tendency toward obesity followed them like ducklings. When you took a child away from obese parents and placed them into a "thin" household, the child still became obese.(*snip*)

This finding was a considerable shock. Standard calorie-based theories blame environmental factors and human behaviors for obesity. Environmental cues such as dietary habits, fast food, junk food, candy intake, lack of exercise, number of cars, and lack of playgrounds and organized sports are believed crucial in the development of obesity. But they play virtually no role."

(Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 22-3.)

2. What was the weight of the twins raised apart?

"Studying identical twins raised apart is another classic strategy to distinguish environmental and genetic factors. Identical twins share identical genetic material, and fraternal twins share 25 percent of their genes.

In 1991, Dr. Stunkard examined sets of fraternal and identical twins in both conditions of being reared apart and reared together. Comparison of their weights would determine the effect of the different environments.

The results sent a shockwave through the obesity-research community. Approximately 70 percent of the variance in obesity is familial.(*snip*)

However, it is immediately clear that inheritance cannot be the sole factor leading to the obesity epidemic.

The incidence of obesity has been relatively stable through the decades. Most of the obesity epidemic materialized within a single generation. Our genes have not changed in that time span.

How can we explain this seeming contradiction?"

(Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 23-4.)

3. What do we consider a change in environment? : My thoughts

I think this is a very interesting study because it compared data from biological parents and adoptive parents.

However, can we assert from the results of this one alone that the influence of genetics was much greater and environmental factors were much less significant?

I believe, as Doctor Fung mentions, the rapid increase in obesity in recent years (since about 1970) has much to do with changes in our living environment (what we eat, irregular lifestyle,etc.),not the genes.

Even those who were slim in their youth may gain five or ten kilos in a short period of time at a certain age, triggered by something (living alone, marriage, parenting, stress from work, etc.). Some people put on weight every time they try dieting to lose weight.

In other words, many of us, in our hearts, have probably noticed that changes in eating habits or our living environment can change our body shape.

■What is the "change in environment" that causes a change in weight here?

The study considers a child living with adoptive parents or twins raised separately to be a "change in living environment," but I think there is a problem with this study.

If a family can afford to take in a child as adoptive parents, don't they have some money to spare and feed their adoptee a somewhat balanced diet three times a day?

Although what they eat and caloric intake may differ from family to family, those changes are not necessarily "environmental changes" that cause changes in weight. Just because the adoptive parents are thin does not mean that adoptees will become thin even if they eat the same diet.

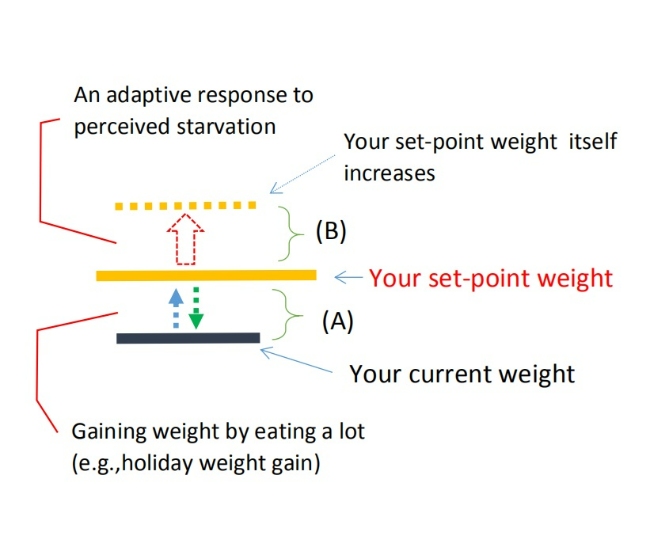

On the contrary, I believe that a fundamental increase in weight and body shape occurs when one’s set-point weight itself goes up, which is induced by intestinal starvation.

And since at least three (+one) factors are required to induce intestinal starvation, living with adoptive parents alone does not necessarily alter one’s set-point weight.

[Related article]

In Japan over the past few decades, our traditional eating habits have been declining. Instead, Westernized eating and diverse work styles have become more prevalent.

Amid these changes, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced when unbalanced diets (high in easily digestible carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, and with a lack of vegetables, etc.) combines with irregular lifestyle habits (skipping breakfast, eating late at night, etc.).

This is what I would like to call the "environmental factors and human behaviors" for the recent obesity epidemic, and while genetic factors are, of course, undeniable, I believe that environmental factors are quite significant.

4. Will the shape of your body from childhood continue?

One thing to note here is that the body shape in childhood (say, around three to five years old) tends to continue into adulthood.

When I think back to my classmates in first and second grade, the girls and boys who were fat (although they were not big eaters) often have a similar body shape even decades later.

From my theory, that means that their set-point weight has not changed, and in this study, if there are no environmental factors that cause changes in their set-point for body weight, then wouldn't the body shape from childhood basically continue?

But, I’m simply wondering what the childhood body shape is due to? Whether it is genetic factors or the way food is prepared during childhood-including weaning-is a question that remains unanswered.

The bottom line

(1) In a study regarding adoptive families and examining how genetic and environmental factors influence being overweight, no correlation was found between the weight of adoptive parents and that of their adoptees. On the other hand, when the adoptees were compared to their biological parents, there was a consistent correlation between the weight of both.

A study of twins raised separately also concluded that "genetic influences are far more significant.”

(2) Many researchers had previously blamed "environmental factors and individual behavior” for the recent obesity epidemic, but this study concluded that genetics had far more impact than environmental factors.

However, I find this study problematic. The fact of children living with adoptive parents or twins raised separately is not necessarily an environmental factor that causes changes in weight.

(3) Of course, I do not think we can ignore the genetic factor, but I believe that the recent obesity epidemic is caused by a combination of what we eat-westernized diets, refined carbohydrates, processed foods, etc.-plus lifestyle changes.

A major change in weight and body shape occurs when one’s set-point weight goes up, which is induced by intestinal starvation.

(4) If there is no significant change in one's set-point weight, I think the body shape from childhood is expected to continue. However, I 'm uncertain what determines childhood body shape, whether it is heredity or the way food is prepared during childhood, including weaning.

09/24/2022

Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

Contents

- How has our Japanese diet changed over the past fifty years?

- The Pima tribe who gained weight under rations, not prosperity

- The newer the diet in history, the less fit the body is

<End note>

1.How has our Japanese diet changed over the past fifty years?

I was born in 1970, about fifty years ago. That was when twenty-five years had passed since the end of the World WarⅡ, and Japan was in the midst of its rapid economic growth.

In retrospect, I feel that the food scene was quite different from what it is today. My parents were farmers in the country side of Osaka, growing rice and mushrooms. We also had about twenty chickens to get fresh eggs.

On the dining table in the morning, there was usually rice, miso soup, pickles, traditional stewed vegetables, and half-dried fish. I remember the family eating together.

Of course, we sometimes ate bread, but my father did physical labor, so rice was an essential part of breakfast.

(Typical Japanese breakfast we used to have)

■The 1970s, when the dining scene changed dramatically

I think it was after 1970 that our dining landscape slowly changed. I had not been taken to restaurants much when I was a kid, but fast food restaurants and other restaurant chains opened one after another in all corners of Japan, and many people began to eat Western food.

McDonald's (since 1971), Kentucky Fried Chicken (since 1970) and family restaurants called Skylark (since 1970) were the most famous among them. In 1974, the first convenience stores (called Seven-Eleven) opened in Tokyo, followed by a rapid increase throughout the country. Instant foods such as cup noodles and frozen foods also increased rapidly, reflecting busy social conditions.

Even in the 1970s, school lunches already had bread as their side dish rather than rice (apparently at the behest of GHQ, which ruled after the war), and those of us who had grown accustomed to such a diet began to prefer bread, noodles, and other wheat-based foods even as adults.

Along with this, we liked to eat meat and (ultra-) processed foods rather than fish with bones.

We began to prefer soft foods to fibrous and hard foods, and the traditional vegetable stews that had been commonly eaten became less and less common.

Our lifestyles also changed dramatically. More and more people began to work at desks rather than at physical jobs. Nighttime lifestyles became the norm, and more people didn't even eat breakfast.

It was probably around this time that obesity began to increase in Japan. Nowadays, it is not unusual to see women over one hundred-kilograms on the streets.

(Percentage of adults with a BMI of 25 or higher: In both men and women, it has been increasing since 1980

One might think that increased caloric intake was the cause of being overweight.

However, on a caloric basis, the average daily caloric intake of the population in 1970 was twenty-two-hundred kcal, yet in 2010 it had decreased to eighteen-hundred-fifty kcal. [1]

To explain this in my theory, the modern diet is often low in fiber and tends to favor easily digestible refined carbohydrates, processed meat and fish products, and fast food, etc., which can, in turn, induce a state of intestinal starvation based on how we combine the foods.

In particular, with changes in eating habits, such as having only two meals a day (skipping breakfast or lunch), light lunches, or late dinners, as well as dietary restrictions due to dieting, many people experience long periods of hunger, making intestinal starvation more likely to occur.

2. The Pima tribe who gained weight under rations, not prosperity

As an example of how obesity has increased as old traditional eating habits have declined and became westernized, I would like to cite a Native American tribe known as the Pima, although the situation is slightly different.

This is the second time I quote from Mr. Taubes' "Why We Get Fat," but this part is very important and may be the key to solving the problems of obesity, diabetes, and other diseases.

"Consider a Native American tribe in Arizona known as the Pima. Today the Pima may have the highest incidence of obesity and diabetes in the United States. Their plight is often evoked as an example of what happens when a traditional culture runs afoul of the toxic environment of modern America. (*snip*)

Between 1901 and 1905, two anthropologists(Russell and Hrdlička) independently studied the Pima, and both commented on how fat they were, particularly the women. (*snip)

Through the 1850s, the Pima had been extraordinarily successful hunters and farmers.

By the 1870s, the Pima were living through what they called the “years of famine.”(*snip*) The tribe was still raising what crops it could but was now relying on government rations for day-to-day sustenance.(*snip*)

What makes this observation so remarkable is that the Pima, at the time, had just gone from being among the most affluent Native American tribes to among the poorest.

Whatever made the Pima fat, prosperity and rising incomes had nothing to do with it; rather, the opposite seemed to be the case.

And if the government rations were simply excessive, making the famines a thing of the past, then why would the Pima get fat on the abundant rations and not on the abundant food they'd had prior to the famines? Perhaps the answer lies in the type of food being consumed, a question of quality rather than quantity.(*snip*)

So maybe the culprit was the type of food. The Pima were already eating everything “that enters into the dietary of the white man,” as Hrdlička said. This might have been key.

The Pima diet in 1900 had characteristics very similar to the diets many of us are eating a century later, but not in quantity, in quality."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 19-23.)

[Related article] Wealthy Ones Get Fat? Poor Ones Get Fat?

In terms of food, I believe that Japanese people in 1970 were eating a lot of different kinds of food than today. There were no convenience stores, and the diet was based on mom's home cooking, with a variety of seasonal vegetables and fish.

In contrast, the modern diet is based on easily digestible carbohydrates and processed meat products, and the variety of food ingredients we eat seems to have decreased dramatically.

Many people are normally worried about gaining weight and are dieting, and then they occasionally splurge and eat high-calorie food as a reward. The situation is different, but if we focus on the inside of the intestines, I can say that it is the same as what happened to the Pima population.

3. The newer the diet in history, the less fit the body is

"The idea is that the longer a particular type of food has been part of the human diet, the more beneficial and less harmful it probably is— the better adapted we become to that food.

And if some food is new to human diets, or new in large quantities, it's likely that we haven't yet had time to adapt, and so it's doing us harm. (*snip*)

The obvious question is, what are the “conditions to which presumably we are genetically adapted”? As it turns out, what Donaldson assumed in 1919 is still the conventional wisdom today: our genes were effectively shaped by the two and a half million years during which our ancestors lived as hunters and gatherers prior to the introduction of agriculture twelve thousand years ago."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 163-4.)

I believe what the author tried to get across was that the modern diet of allowing large amounts of carbohydrates is not genetically compatible with our bodies, and that eating meat and its fat may be more compatible and less harmful to us on a genetic level.

I will quote this passage above to explain my intestinal starvation mechanism.

Suppose (and it makes more sense) that God created a genetic blueprint for people to "store body fat" in case they could not find food.

If the state of "no food" (starvation) was recognized when all food was digested in the entire intestinal tract, then during the hunting-and-gathering age and farming age when people ate wild boar meat, nuts, vegetables with tough cell walls, and unrefined grains, etc., their intestines would not have been in a state of complete starvation even if they couldn’t eat anything for a whole day (because of the long intestines).

In contrast, a modern diet high in quickly digested foods —such as refined wheat and rice, starches, processed meat and fish products, and fast food—can, depending on the combination, lead to a state of intestinal starvation in as little as half a day.

I believe it is the entire intestines (or it may be the small intestine only) that makes all the decisions, and it goes to show that inside the gut, many of us are starving more today than in the past.

End note

People sometimes say, "Japanese food culture is healthy by world standards," but I believe this to be a relic of the past until around the year 2000 at the latest. Now, I feel that traditional Japanese food culture is dying in the average household.

Children who grew up eating fast food are now in their fifties and sixties, and their children are now in their thirties. Thus, in about fifty to sixty years (about two generations), the opportunity to eat traditional foods will have faded away, and the food culture will change greatly.

And, with the shift in diet, it seems like that diseases such as diabetes, kidney disease, heart disease, cancer, and stroke, which were once not as common, are on the rise, just as they are in the Western countries.

References:

[1]Yasuo Kagawa(香川靖雄) , Clock Gene Diet (時計遺伝子ダイエット), 2012, Page 15.

06/12/2022

Can Thermodynamics Explain Why We Gain Weight?

-

Contents

-

- What does the first law of thermodynamics tell us?

- The human body is a mass of chemical reactions

- Calories eaten is not the same as calories the body takes in. My thoughts

<The bottom line>

First, please refer to the following article.

The Calorie Principle and Weight Gain; The Causality Has Been Obscure

According to Gary Taubes, the author of Why We Get Fat (2010), in the early 1900’s, Carl von Noorden, a German diabetes specialist, first argued that we get fat because we take in more calories than we expend.

This view has persisted to the present day, leading many experts to firmly believe that excessive caloric intake and/or lack of exercise are the primary causes of weight gain[1]. This time, I would like to share the “law of thermodynamics,” which was said to be the basis for that theory. Mainly quoted from the book, it is so interesting that I think it is worth reading.

1. What does the first law of thermodynamics tell us?

"There are three laws of thermodynamics, but the one that the experts believe is determining why we get fat is the first one.

This is also known as the law of energy conservation: all it says is that energy is neither created nor destroyed but can only change from one form to another.

Blow up a stick of dynamite, for instance, and the potential energy contained in the chemical bonds of the nitroglycerin is transformed into heat and the kinetic energy of the explosion.

Because all mass-our fat tissue, our muscles, our bones, our organs, a planet or star, Oprah Winfrey-is composed of energy, another way to say this is that we can't make something out of nothing or nothing out of something.

This is so simple that the problem with how the experts interpret the law begins to become obvious.

All the first law says is that if something gets more or less massive, then more energy or less energy has to enter it than leave it.

It says nothing about why this happens. It says nothing about cause and effect. It doesn't tell us why anything happens; it only tells us what has to happen if that thing does happen. A logician would say that it contains no causal information.(*snip*)

Imagine that, instead of talking about why we get fat, we're talking about why a room gets crowded.

Now the energy we're discussing is contained in entire people rather than just their fat tissue.

Ten people contain so much energy, eleven people contain more, and so on. So what we want to know is why this room is crowded and so overstuffed with energy- that is, people.

If you asked me this question, and I said, Well, because more people entered the room than left it, you'd probably think I was being a wise guy or an idiot. Of course more people entered than left, you'd say. That's obvious. But why? And, in fact, saying that a room gets crowded because more people are entering than leaving it is redundant-saying the same thing in two different ways-and so meaningless.

Now, borrowing the logic of the conventional wisdom of obesity, I want to clarify this point. So I say, Listen, those rooms that have more people enter them than leave them will become more crowded. There's no getting around the laws of thermodynamics. You'd still say, Yes, but so what? Or at least I hope you would, because I still haven't given you any causal information.

This is what happens when thermodynamics is used to conclude that overeating makes us fat. (*snip*)

The National Institutes of Health says on its website, “Obesity occurs when a person consumes more calories from food than he or she burns.”

By using the word “occurs,” the NIH experts are not actually saying that overeating is the cause, only a necessary condition.

They're being technically correct, but now it's up to us to say, Okay, so what? Aren't you going to tell us why obesity occurs, rather than tell us what else happens when it does occur?”

(Gary Taubes. 2011. Why We Get Fat. Pages 73-5.)

2. The human body is a mass of chemical reactions

"The first law states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed. In other words, energy can be converted from one form to another, but the total amount of energy in the universe remains constant. How might this law apply to weight management?

Suppose someone has stable weight over time. The first law dictates that, in theory, the number of calories consumed by this individual in the form of food is equal to the calories the individual expends during metabolism and activity. In other words, 'calories in = calories out’.(*snip*)

However, the first law of thermodynamics actually refers to what are known as ‘closed systems' -ones that can exchange heat and energy with their surroundings, but not matter. Is this true for human beings?

Actually, no: the human body does indeed exchange matter with its surroundings, principally in the form of the food (matter in) and as waste products such as urine and faeces (matter out).

Also, technically speaking, the first law refers to systems in which chemical reactions do not take place.

But the human body is essentially a mass of chemical reactions. So, here again, the first law of thermodynamics cannot apply where weight management is concerned."

(Jone Briffa. 2013. Escape the Diet Trap. Pages 63-4. )

3. Calories eaten is not the same as calories the body takes in. My thoughts

Two authors have made excellent points about the relationship between thermodynamics and weight management. Based on those thoughts, I would also like to mention two points about the relationship between thermodynamics and my theory.

(1)What constitutes "caloric intake"

I also believe that if a person has a stable weight over many years, then the “energy entering the body” and the “energy used within the body” must be balanced.

The issue, however, lies in determining at what point we have "taken in" energy.

If we consider “caloric intake” as calories from food at the point it enters our mouths, then it’s not surprising that for some people, this doesn’t equal the energy expended. This is because, as Dr. Briffa pointed out, our bodies are not "closed systems."

If we consider energy actually absorbed from the gut to be "calories consumed," as gut microbiologists believe the gastrointestinal tract is outside the body, then it should be considered more of a "closed system."

Of course, it’s impossible to calculate each person’s absorption efficiency. Therefore, we currently determine the calorie content of individual foods based on the Atwater coefficient, summing these values to estimate daily caloric intake.

However, we should keep in mind that these are only estimates or approximations. I believe that the actual amount of nutrients and energy absorbed varies with factors such as cooking methods, food digestibility, combination of foods, exercise intensity, and hunger levels,etc.

While von Noorden’s claim that “we get fat because we consume more calories than we expend” is true in a sense, it’s unclear exactly when we can consider energy as being “consumed” by the body.

(2) When energy intake increases

Based on my intestinal starvation mechanism concept, even if a person who has maintained the same weight over the years, significantly reduces their usual caloric intake (e.g. about two thousand kcal daily) and the intake of carbohydrates, but meets the "three factors + one" criteria that cause intestinal starvation, they will gain weight (this means that the set-point weight itself has risen due to an increase in absorption ability).

[Related article] →Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

Of course, weight gain occurs when you return to your original diet afterward. In this case, since absorption efficiency itself has increased compared to before, both body fat and lean tissue contribute to the weight gain.

In short, even though you are eating the same amount of food (calories) as before, you are taking in more energy and nutrients into your body than before, which means you are getting bigger/fatter. In the words of Taubes, "a room crowded with ten people now has eleven people," and in this case, it is “intestinal starvation” that has caused it.

The bottom line

(1)The basis for experts believing that “we gain weight because we consume more calories than we burn” is the law of energy conservation (the first law of thermodynamics).

(2)Since the human body is a mass of chemical reactions and not a "closed system," it does not make sense to compare the total calories actually eaten with the calories expended. In this case, the "first law of thermodynamics" does not hold.

(3)If we base it on the calories actually absorbed in the intestines, it should be closer to a "closed system" and be balanced with the calories expended through one’s basal metabolism and activity,etc.

(4)When intestinal starvation is induced, weight gain can occur even if you are consuming the same amount of calories as before, suggesting an increase in the set-point weight.

In this case, the absorption ability has increased, meaning that more energy and nutrients are taken into the body, so weight gain involves not only body fat but also an increase in lean tissue.

05/22/2022

The Calorie Principle and Weight Gain; The Causality Has Been Obscure

Contents

- The birth of the "calories-in/calories-out" theory

- Obesity is still on the rise

- Carl von Noorden's book

In Japan, most people believe that “taking in too many calories and lack of exercise are the causes of being overweight,” which I believe is largely due to statements made by experts, nutritionists, etc. on television.

When I launched this website in 2014, I wanted to argue against that in my website, but I couldn’t find any academic papers and other resources that showed the "causal relationship between caloric intake and becoming obese."

However, around a year after I started blogging, I came across this great book: “Why We Get Fat” written by Gary Taubes. It is surprising that it was published in Japanese in 2013.

After all, this is the only book I can rely on. In explaining what I want to say, I first needed to let you know that, "the direct cause of being overweight is not determined by overeating.”

1. The birth of the "calories-in/calories-out" theory

"Ever since the early 1900s, when the German diabetes specialist Carl von Noorden first argued that we get fat because we take in more calories than we expend, experts and non-experts alike have insisted that the laws of thermodynamics somehow dictate this to be true.

Arguing to the contrary, that we might actually get fatter for reasons other than the twin sins of overeating and sedentary behavior, or that we might lose fat without consciously eating less and/or exercising more, has invariably been treated as quackery- "emotional and groundless," as the Columbia University physician John Taggart insisted in the 1950s in his introduction to a symposium on obesity. “We have implicit faith in the validity of the first law of thermodynamics," he added.

Such faith is not misplaced. But that does not mean that the laws of thermodynamics have anything more to say about getting fat than any other law of physics.

Newton's laws of motion, Einstein's relativity, the electrostatic laws, quantum mechanics -they all describe properties of the universe we no longer question.

But they don't tell us why we get fat. They say nothing about it, and this is true of the laws of thermodynamics as well.

It is astounding how much bad science-and so bad advice, and a growing obesity problem-has been the result of the experts' failure to understand this one simple fact. The very notion that we get fat because we consume more calories than we expend would not exist without the misapplied belief that the laws of thermodynamics make it true."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 72-3.)

(*snip*)

"In 1934, a German pediatrician named Hilde Bruch moved to America, settled in New York city. She was “startled,” as she later wrote, by the number of fat children she saw-”really fat one, not only in the clinics, but also on the streets, subways, and in schools.” This was two decades before the first McDonald's franchises was born, and more to the point, 1934 was in the depths of the Great Depression.

Bruch put in effort in the treatment of obese children. It was hard to avoid, she said, the simple fact that these children had, after all, spent their entire lives trying to eat in moderation and control their weight as directed, and yet they remained obese.

The physicians of Bruch's era weren't thoughtless, and the doctors of today are not, either.

They merely have a flawed belief system-a paradigm-that stipulates that the reason we get fat is clear and incontrovertible, as is the cure.

We get fat, our physicians tell us, because we eat too much and/or move too little, and so the cure is to do the opposite. (*snip*)

▽“The fundamental cause of obesity and overweight," as the World Health Organization says, “is an energy imbalance between calories consumed on one hand, and calories expended on the other hand."

We get fat when we take in more energy than we expend (a positive energy balance, in the scientific terminology), and we get lean when we expend more than we take in (a negative energy balance).

Food is energy, and we measure that energy in the form of calories. So, if we take in more calories than we expend, we get fatter. If we take in fewer calories, we get leaner.

This way of thinking about our weight is so compelling and so pervasive that it is virtually impossible nowadays not to believe it. Even if we have plenty of evidence to the contrary-no matter how much of our lives we've spent consciously trying to eat less and exercise more without success— it's more likely that we'll question our own judgment and our own willpower than we will this notion that our adiposity is determined by how many calories we consume and expend."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 3-6.)

2. Obesity is still on the rise

"Consider the obesity epidemic. Here we are as a population getting fatter and fatter.

Fifty years ago, one in every eight or nine Americans would have been officially considered obese, and today it's one in every three. Two in three are now considered overweight, which means they’re carrying around more weight than the public-health authorities deem to be healthy.

Throughout the decades of this obesity epidemic, the calories-in/calories-out, energy-balance notion has held sway, and so the health officials assume that either we're not paying attention to what they've been telling us -eat less and exercise more-or we just can't help ourselves.

Malcolm Gladwell discussed this paradox in The New Yorker in 1998.

“We have been told that we must not take in more calories than we burn, that we cannot lose weight if we don't exercise consistently," he wrote. “That few of us are able to actually follow this advice is either our fault or the fault of the advice. Medical orthodoxy, naturally, tends toward the former position. Diet books tend toward the latter. Given how often the medical orthodoxy has been wrong in the past, that position is not, on its face, irrational. It's worth finding out whether it is true.”

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 7-8.)

(Gary Taubes’s thoughts on the relationship between thermodynamics and weight gain)

"Obesity is not a disorder of energy balance or calories-in/ calories-out or overeating, and thermodynamics has nothing to do with it. If we can't understand this, we'll keep falling back into the conventional thinking about why we get fat, and that's precisely the trap, the century-old quagmire, that we're trying to avoid."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 73.)

3. Carl von Noorden's book

Japanese television programs still continue to show doctors and nutritionists confidently saying, "The cause of weight gain is, of course, overeating or lack of exercise,”which I find disgusting. However, I hope you can see how flimsy and baseless these theories are.

By the way, I obtained Carl von Noorden's book (archive), which is shown at the beginning of the quotation. You can read it at the following link:

10/15/2021

The Combination of Undernutrition and Obesity Among the Poor Can be Possible

Contents

- The case of undernutrition and obesity

- What should we do?

- Being underweight and being overweight can coexist: My thoughts

Most of the parts of this article are citations from a book, but at the end of this article, I will explain how it is related to my experience.

[Related article] → Wealthy Ones Get Fat? Poor Ones Get Fat?

1. The case of undernutrition and obesity

"This combination of obesity and malnutrition or undernutrition (not enough calories) existing in the same populations is something that authorities today talk about as though it were a new phenomenon, but it's not. Here we have malnutrition or undernutrition coexisting with obesity in the same population eighty years ago.

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books. 2011. Page 24.)

(In the mid-1930s, New York City)

In 1934, a young German pediatrician named Hilde Bruch moved to America, settled in New York city, and was 'startled,' as she later wrote, by the number of fat children she saw—'really fat ones, not only in clinics, but on the streets and subways, and in schools. '(*snip*)

But this was New York City in the mid-1930s. This was two decades before the first Kentucky Fried Chicken and McDonald's franchises, when fast food as we know it today was born. This was half a century before supersizing and high-fructose corn syrup.

More to the point, 1934 was the depths of the Great Depression, an era of soup kitchens, bread lines, and unprecedented unemployment.

One in every four workers in the United States was unemployed. Six out of every ten Americans were living in poverty. In New York City, where Bruch and her fellow immigrants were astonished by the adiposity of the local children, one in four children were said to be malnourished. How could this be?(*snip*)

It was hard to avoid, Bruch said, the simple fact that these children had, after all, spent their entire lives trying to eat in moderation and so control their weight, or at least thinking about eating less than they did, and yet they remained obese."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 3, 4.)

(The case of a native American tribe, the Sioux, in 1930's)

"Two researchers from the University of Chicago studied Native American tribe, the Sioux living on the South Dakota Crow Creek Reservation. These Sioux lived in shacks 'unfit for occupancy,' often four to eight family members per room. Fifteen families, with thirty-two children among them, lived “chiefly on bread and coffee.” This was poverty almost beyond our imagination today.

Yet their obesity rates were not much different from what we have today in the midst of our epidemic: 40 percent of the adult women on the reservation, more than a quarter of the men, and 10 percent of the children, according to the University of Chicago report, 'would be termed distinctly fat.'

But the researchers noted another pertinent fact about these Sioux: one-fifth of the adult women, a quarter of the men, and a quarter of the children were 'extremely thin.'

The diets on the reservation, much of which, once again, came from government rations, were deficient in calories, as well as protein and essential vitamins and minerals. The impact of these dietary deficiencies was hard to miss: 'Although no counts were taken, even a casual observer could not fail to note the great prevalence of decayed teeth, of bow legs, and of sore eyes and blindness among these families.'"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 23-4.)

(In the slums of São Paulo, Brazil)

"This is from a 2005 New England Journal of Medicine article, ''A Nutrition Paradox-Underweight and Obesity in Developing Countries,' written by Benjamin Caballero, head of the Center for Human Nutrition at Johns Hopkins University.

Caballero describes his visit to a clinic in the slums of São Paulo, Brazil.

The waiting room, he writes, was 'full of mothers with thin, stunted young children, exhibiting the typical signs of chronic undernutrition.

Their appearance, sadly, would surprise few who visit poor urban areas in the developing world. What might come as a surprise is that many of the mothers holding those undernourished infants were themselves overweight.'(*snip*)

If we believe that these mothers were overweight because they ate too much, and we know the children are thin and stunted because they're not getting enough food, then we're assuming that the mothers were consuming superfluous calories that they could have given to their children to allow them to thrive.

In other words, the mothers are willing to starve their children so that they themselves can overeat. This goes against everything we know about maternal behavior. (*snip*)

Caballero then describes the difficulty that he believed this phenomenon presents: ''The coexistence of underweight and overweight poses a challenge to public health programs, since the aims of programs to reduce undernutrition are obviously in conflict with those for obesity prevention.'

Put simply, if we want to prevent obesity, we have to get people to eat less, but if we want to prevent undernutrition, we have to make more food available. What do we do?"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 30-1.)

2. What should we do?

"In the early 1970s, nutritionists and research-minded physicians would discuss the observations of high levels of obesity in these poor populations, and they would occasionally do so with an open mind as to the cause. (*snip*)

Here's Rolf Richards, the British-turned-Jamaican diabetes specialist, discussing the evidence and the quandary of obesity and poverty in 1974, and doing so without any preconceptions: "It is difficult to explain the high frequency of obesity seen in a relatively impecunious [very poor] society such as exists in the West Indies, when compared to the standard of living enjoyed in the more developed countries.

Malnutrition and subnutrition are common disorders in the first two years of life in these areas, and account for almost 25 per cent of all admissions to pediatric wards in Jamaica. Subnutrition continues in early childhood to the early teens. Obesity begins to manifest itself in the female population from the 25th year of life and reaches enormous proportions from 30 onwards.'

When Richards says 'subnutrition,' he means there wasn't enough food. From birth through the early teens, West Indian children were exceptionally thin, and their growth was stunted. They needed more food, not just more nutritious food. Then obesity manifested itself, particularly among women, and exploded in these individuals as they reached maturity.

This is the combination we saw among the Sioux in 1928 and later in Chile— malnutrition and/or undernutrition or subnutrition coexisting in the same population with obesity, often even in the same families. (*snip*)

Referring to obesity as a 'form of malnutrition' comes with no moral judgments attached, no belief system, no veiled insinuations of gluttony and sloth. It merely says that something is wrong with the food supply and it might behoove us to find out what.(*snip*)

Again, the coexistence of underweight and overweight in the same populations and even in the same families doesn't pose a challenge to public-health programs; it poses a challenge to our beliefs about the cause of obesity and overweight."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 29-32.)

3. Being underweight and being overweight can coexist: My thoughts

<About undernutrition and overweight>

First, I would like to explain, based on my experience, that the coexistence of undernutrition and obesity are not contradictory messages.

I repeat that when I was very thin, under forty kilograms, at first, I was eating high-calorie foods such as deep-fried foods or sweet, but I couldn’t gain weight. And then, I realized that I could gain weight by digesting all the foods in my whole intestines and inducing intestinal starvation.

The easiest way to induce intestinal starvation was to eat digestible refined carbohydrates (rice, white bread, noodles, starches, etc.) and a little easy-to-digest protein (and not to eat other foods), but since it lacked energy and essential nutrients for my body, I felt dizzy from the undernutrition.

If I ate eggs, vegetables, beans, or fish, or drank milk to add more essential nutrients, though the nutritional profile was better, I couldn’t gain any weight. For me, it was because I couldn’t digest them well.

IIn short, a higher ratio of digestible refined carbohydrates in the meals and eating fewer fibrous vegetables, fat, and other indigestible foods are more likely to induce intestinal starvation and cause one’s set-point weight to increase.

It’s probably certain that a deficiency of vitamins and/or minerals can cause illnesses, but being overweight is not contradicting being in a state of undernutrition.

<About the coexistence of being underweight and overweight>

Getting back to what Caballero refered to, even if people eat similar foods in the same group, it may lead to a different result in the body.

Some people who digested all the foods in their whole intestines may have gained weight—which means their set-point weight went up by intestinal starvation— and ended up becoming overweight.

However, those who were not able to digest all the foods in their whole intestines remained underweight. I believe that leaving Just a little bit of undigested food in the intestines makes it hard to induce intestinal starvation. (Being extremely thin can cause poor digestion, so it makes it even harder for them to induce intestinal starvation.) A small difference sometimes makes a big difference in the end result.

To sum up, what happened in the groups in poverty situations is a similar phenomenon that is happening in our modern society.

When someone doesn't eat much and is fat, we tend to assume that they are inactive or have a slow metabolism. And when someone who eats a lot but is thin, we tend to assume that they are active or have a fast metabolism.

Most researchers just try to fit everything into the theory that “fat people eat too much or are physically inactive” for some reason.

However, if we look at these ideas I’ve presented with an open mind, we can say that this is the same phenomenon as the "coexistence of thin and obese" in the same population.

At the risk of repeating myself, being overweight is not necessarily the consequence of overeating.