— Topics —

Genetic factors vs environmental factors

2025.03.03

The Rise in Obesity is Closely Linked to the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods

Summary

(1) The NOVA classification system, developed in 2009 by a research group at the University of São Paulo, categorizes foods into four groups based on the degree and purpose of processing rather than type or their nutritional content.

【1】Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

【2】Processed culinary ingredients

【3】Processed foods (PFs)

【4】Ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are formulations made from multiple ingredients and undergo numerous industrial processes. They include sweet or savory snacks, confectioneries, instant foods, processed meat products such as sausages and ham, and most fast foods.

Increased UPF consumption is believed to be linked to rising rates of obesity and diet-related diseases.

(2) UPFs are high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, salt, saturated fats, and trans fats, making them energy-dense. On the other hand, they are poor sources of fiber, protein, and micronutrients.

Additionally, they often contain flavorings, colorings, emulsifiers, preservatives, and other cosmetic additives.

(3) Since the 1980’s, UPF consumption has surged not only in developed countries but also in developing nations. UPFs now account for more than 50% of total daily energy intake on average in the U.S., U.K., and Canada.

(4) Several studies examining the relationship between UPF consumption and obesity have clearly shown that higher UPF intake is associated with an increased risk of obesity. In contrast, greater consumption of natural foods, such as vegetables, has been found to be inversely correlated with obesity.

(5) A U.S. research group found that individuals with high UPF consumption tend to eat fewer natural foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and fish, leading to a significant decline in overall diet quality.

(6) Processed food diets may result in lower diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) compared to whole-food diets, potentially increasing net energy intake. Additionally, UPF diets may lead to overeating because they provide less satiety and make individuals feel hungrier than unprocessed food diets.

<My thought>

(7) Generally, UPFs are considered to promote obesity when consumed in excess due to their high energy density. However, I want to highlight the risk of “ultra-processing” itself. Since UPFs are low in nutrients and fiber, and are easily digested, if a diet is skewed toward refined carbohydrates and UPFs while lacking natural foods like vegetables, it can lead to intestinal starvation, potentially raising the body's set-point weight.

(8) It is not an overstatement to say that the sharp rise in being overweight, obesity, and many lifestyle-related diseases coincided with the rapid industrialization of food processing in the 1970’s and 80’s.

(9) The World Obesity Federation (WOF) warns that without policy changes and effective obesity prevention measures, more than half of the global population will be classified as obese or overweight by 2035. In my opinion, instead of focusing solely on “calories,” policies need to emphasize factors such as the degree of food processing, the number of chews, and the digestibility of food.

【 Full text 】

-

Contents

-

- Food classification by NOVA

- The Issues with Ultra-Processed Foods

- Consumption of UPFs and its association with obesity

- Impact of UPFs on overall diet

(1) Decrease in overall diet quality

(2) Increase in net energy intake

(3)Effects on ad libitum energy intake - Why do UPFs cause weight gain?

- Desired future measures

The endless diet wars among factions in various diets—such as low-carb, ketogenic, paleo, low-fat, and vegan—have caused substantial public confusion and fostered mistrust in nutritional science. However, it is not widely known that diverse diets recommendations often share a common piece of advice: to avoid ultra-processed foods[1].

Empirical evidence has shown that the rising obesity rates closely parallel the increased consumption of ultra-processed foods in many countries.

In this discussion, I’d like to explore the reasons behind this and, finally, mention how it relates to my intestinal starvation theory.

1. Food classification by NOVA

NOVA (not a acronym) is the food classification that categorizes foods based on the degree and purpose of food processing, rather than their nutritional content. It was developed in 2009 by a research group at the University of São Paulo in Brazil[2].

Conventional food classification systems categorize foods and ingredients based on their botanical origin or animal species, and nutrient composition.

As a result, whole grains are often grouped with breakfast cereals or cookies, and fresh chicken or pork are often classified alongside chicken nuggets or sausages.

When considering their their impact on health and disease, conventional food classifications no longer worked well[3].

NOVA classifies foods into four groups based on the nature, extent, and purpose of the industrial processing they undergo.

(1)Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

Fresh fruits and vegetables, and other natural foods (such as grains, milk, fish, and meat) that have undergone processes like removing inedible parts, drying, grinding, pasteurization, chilling, freezing, or vacuum-packaging.

(2)Processed culinary ingredients

Substances derived from Group 1 foods or from nature through processes that include pressing, refining, milling, or drying, such as oils, butter, sugar, and salt. These processed culinary ingredients are typically not consumed on their own.

(3)Processed foods (PFs)

These are typically made by adding Group 2 substances to Group 1 foods. Examples include canned vegetables, fruit in syrup, canned fish, cheese, and freshly made breads.

(4)Ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

These are formulations created by combining many ingredients and undergoing a sequence of industrial processes. Examples include breakfast cereals, soft drinks and fruit juices, sweet or savory snacks, confectioneries, instant foods, reconstituted meat products such as sausages and nuggets, and most fast food items[3,4].

2. The issues with ultra-processed foods

Food processing, in essence, refers to “various operations by which raw foodstuffs are made suitable for consumption, cooking, or storage,” and virtually all foods undergo some form of processing before being eaten. Therefore, processing itself is not inherently bad.

However, ultra-processed foods are not modified foods but formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives through multiple industrial processes, with little to no Group 1 natural foods[3].

These foods are high in refined grains, added sugars, salt, saturated fats, and trans fats, making them energy-dense. On the other hand, they are poor sources of dietary fiber, protein, and micronutrients.

Additionally, flavorings, colorings, emulsifiers, non-sugar sweeteners, and other cosmetic additives are often added to these products to mask undesirable qualities of the final product[5].

Nevertheless, since the 1980s, the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has rapidly increased not only in developed countries but also in developing nations, largely driven by transnational corporations.

UPFs are highly appealing because they are hyper-palatable and addictive, inexpensive, have a long shelf life, and can be consumed anytime, anywhere[3].

The evidence based on the NOVA classification so far suggests that the decline in minimally processed foods and home cooking, alongside the replacement of food supplies with ultra-processed foods, is associated with unhealthy nutritional profiles and an increase in several diet-related diseases[3].

3. Consumption of UPFs and its association with obesity

In studies on adults reporting the proportion of total daily energy intake from UPFs, the highest levels (on average) were reported in the USA (55.1–56.1%), followed by the UK (53–54.3%), Canada (45.1–51.9%), France (29.9–35.9%), Brazil (20–29.6%), Spain (24.4%), and Malaysia (23%)[6].

A cross-sectional study (2005–2014) on American adults, who were found to consume an average of 56.1% of their total energy intake from UPFs, revealed significant differences across quintiles. Those in the highest quintile (Note 1) consumed 84.5% of their total energy intake from UPFs, while those in the lowest quintile accounted for 25.4%[7].

(Note 1: Quintile refers to one of five equal measurements that a set of things can be divided into)

♦A cross-sectional time series study conducted in fifteen Latin American countries revealed that sales of UPFs were associated with changes in body weight in twelve of these countries from 2000 to 2009[8].

A cross-sectional study based on data from Brazil’s 2008–2009 Household Budget Survey found that household availability of UPFs was positively correlated with both the average BMI and obesity prevalence. Those in the highest quartile (Note 2) of household consumption of UPFs were 37% more likely to be obese compared to those in the lowest quartile[9].

(Note 2: Quartile refers to one of four equal measurements that a set of things can be divided into)

♦A study involving 6,143 participants from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008–2016) classified foods recorded in four-day food diary according to the NOVA system. Consumption of UPFs was associated with increases in BMI, waist circumference, and obesity rates in both men and women. For every 10% increase in UPF consumption, the obesity rate increased by 18%.

Higher consumption of UPFs was observed among men, white British individuals, smokers, younger people, and those in lower social class groups[10].

♦A cross-sectional study involving 19,363 adults aged 18 and older from the 2004 Canadian Community Health Survey, found that individuals in the highest quintile of UPF consumption were 32% more likely to be obese compared to those in the lowest quintile. Higher UPF intake was associated with being male, younger age, lower educational attainment, physical inactivity, smoking, and being born in Canada[4].

♦A prospective cohort study conducted since 1999 among graduates of the University of Navarra in Spain tracked 8,451 participants who were not overweight at baseline for about nine years. Those in the highest quartile of UPF consumption had a 26% higher risk of developing overweight or obesity compared to those in the lowest quartile.

Moreover, on average, they consumed more fast food, fried foods, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages, while, in contrast, their vegetable intake was the lowest. A higher consumption of UPFs was associated with lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet[11].

3. Impact of UPFs on overall diet

(1) Decrease in overall diet quality

♦A U.S. research group analyzed data on 5,919 children and 10,064 adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2015-2018) to investigate the relationship between UPF consumption and overall diet quality. Diet quality was assessed using the American Heart Association (AHA) diet score and Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2015 score.

The estimated proportion of children with a poor diet gradually increased from 31.3 % in the lowest quintile of UPF consumption to 71.6 % in the highest quintile. Similarly, among adults, this proportion rose from 18.1 % in the lowest quintile to 59.7 % in the highest quintile.

As UPF intake increased, the consumption of healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, and fish significantly decreased, while the intake of unhealthy foods such as refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, and added sugars increased.

The research group concluded that higher consumption of UPFs was associated with substantially lower diet quality among children and adults. These findings were consistent with previous studies conducted in several countries[12].

♦An Italian research group hypothesized that meal timing could also be linked to food processing and conducted a study to test this. They analyzed data on 8,688 individuals from the Italian Nutrition & Health Survey (INHES), conducted between 2010 and 2013. Subjects were classified as early or late eaters based on the population’s median timing for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Results showed that late eaters (breakfast after 7 AM, lunch after 1 PM, and dinner after 8 PM) were less likely to consume unprocessed or minimally processed foods compared to early eaters, while they consumed more processed foods (PFs) and UPFs. Late eating was also inversely associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet[13].

The Mediterranean diet, which primarily consists of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish, has been shown to be linked to reduced weight gain[14].

(2) Increase in net energy intake

A group of researchers in the U.S. conducted a crossover comparative study to ascertain the net energy intake of two different diets: one consisting of specific processed foods and the other of an isocaloric whole-food (WF) diet. Eighteen subjects consumed two types of sandwiches with the same calorie content but differing in processing levels.

The WF meal consisted of multigrain bread (containing whole sunflower seeds and whole-grain kernels) and cheddar cheese, while the PF meal consisted of white bread and a processed cheese product.

In this study, diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT)(Note 3) after consuming the PF meal was 46.8 % lower than that of the WF meal. The researchers concluded that this difference in DIT led to a 9.7 % increase in net energy-gain for the PF meal[15].

(Note 3) Diet induced thermogenesis (DIT) is the process by which the body increases its energy expenditure for several hours in response to food intake.

Regarding the significant reduction in diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) observed with the PF meal, the researchers provided the following analysis:

Compared to whole foods, PFs are characterized by lower nutrient density (a lower content and diversity of nutrients per calorie), less dietary fiber, and an excess of simple carbohydrates. As a result, PFs are structurally and chemically simpler than whole foods, making them easier to digest[15,16].

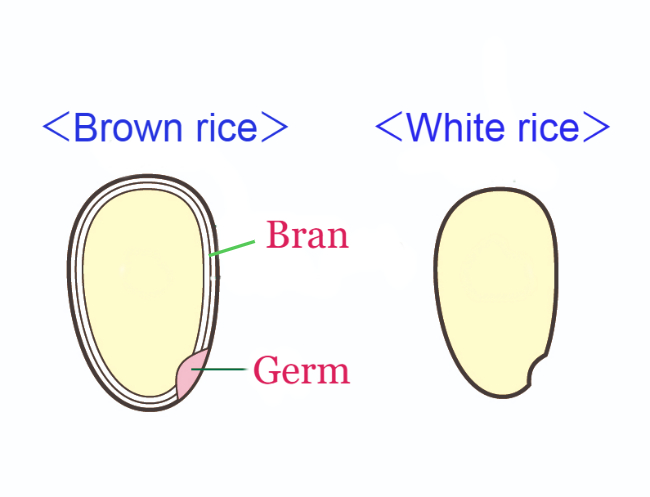

In grain refinement, most of the bran and germ are removed, resulting in the loss of nutrients (such as vitamins, minerals, and proteins), fiber, and phenols they provide.

Consequently, PFs tend to have fewer metabolites, leading to reduced enzyme production and peristalsis (Note 4), easier absorption, and less secondary metabolism—all of which contribute to lower DIT[15, 17].

Additionally, the loss of fiber reduces meal bulk and tends to slow satiety, both of which can lead to an increase in daily caloric intake[15, 18].

(Note 4:the repeated movements made by the muscle walls in the digestive tract tightening and then relaxing)

(3)Effects on ad libitum energy intake

A group of U.S. researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the effects of ultra-processed versus unprocessed diets on ad libitum energy intake in twenty adults with stable body weight. Subjects were randomly assigned to either the ultra-processed or calorie-matched unprocessed diet for two weeks, followed by the alternate diet for another two weeks.

In this experiment, participants were allowed to eat additional food after meals. As a result, they consumed more energy (459±105 kcal /day) during the ultra-processed diet and gained 0.4±0.1 kg of body fat. In contrast, they lost 0.3±0.1 kg of body fat during the unprocessed diet.

Fasting blood tests showed that levels of the appetite-suppressing hormone peptide YY (PYY) increased during the unprocessed diet as compared with both the ultra-processed diet and baseline. Also, levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin decreased during the unprocessed diet compared to baseline. This suggests that participants felt less hungry during the unprocessed diet, whereas the ultra-processed diet provided less satiety, making participants feel hungrier[19].

4. Why do UPFs cause weight gain?

I would like to explain the link between consumption of UPFs and an increase in obesity from the perspective of intestinal starvation.

Since the development of the NOVA classification, various studies have focused on the degree of food processing rather than calorie content, which is noteworthy.

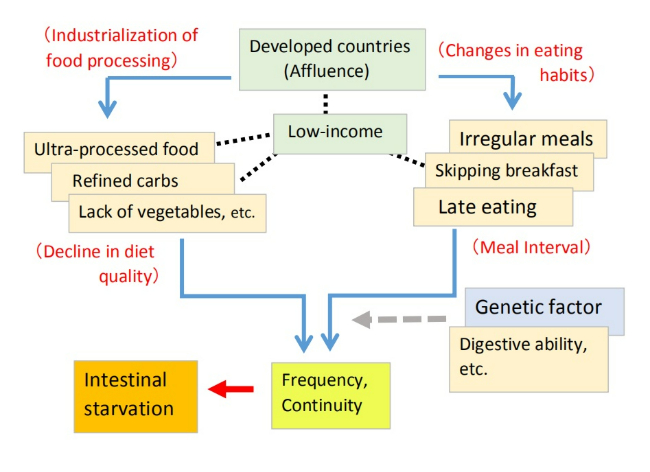

In the past, factors such as refined carbohydrates, fast food, late-night eating, lack of vegetables, wealth, and poverty have been discussed as causes of being overweight. However, how these factors interact had not been clearly proven.

This time, research has shown that increased UPF consumption itself is linked to an overall decline in diet quality, lack of vegetables, late-night eating, and lower-income groups in developed countries.

Through this blog, I have explained that a combination of factors—such as an unbalanced diet leaning toward refined carbohydrates and UPFs, a lack of vegetables, and an irregular lifestyle—can induce intestinal starvation, potentially raising the body's set-point weight.

UPFs are often high in energy density, so they are generally believed to promote obesity when overeaten. However, I believe the biggest issue is the "ultra-processing" itself, as these foods are digested and absorbed more quickly than natural foods.

If the diet is skewed toward refined carbohydrates and UPFs, and the overall diet quality declines, blood sugar levels can fluctuate sharply. Additionally, since these foods leave nothing behind in the intestines after digestion, intestinal starvation can be triggered (Note 5).

The fact that adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the consumption of natural foods like vegetables are inversely correlated with obesity supports my perspective.

In Japan, In my opinion, the consumption of UPFs such as instant foods, cookies, sweet bread, and chocolate confection is not necessarily low. However, one reason Japan’s obesity rate is lower than in Western countries may be its rice-based food culture, and the fact that many Japanese people still follow traditional eating habits.

(Note 5: Foods high in fat, such as ice cream, take longer to digest and may help prevent intestinal starvation.)

5. Desired future measures

The World Obesity Federation (WOF) warns that if policy directions remain unchanged and no effective measures are taken to prevent and treat obesity, more than half of the global population will be classified as overweight or obese by 2035.

I think this suggests that past policies focused solely on "calories in/ calories out" have not been particularly effective.

What we need now is a shift in focus from "calories" to factors such as the degree of food processing, the number of chews, and digestibility in policymaking.

With traditional dietary habits in many parts of the world, minimally processed natural foods were gradually digested in the digestive tract, allowing energy and nutrients to enter the bloodstream over several hours, while indigestible components like fiber helped maintain gut health.

Even if refined carbohydrates—such as white rice or bread—were included, the overall dietary quality likely remained high.

Even when people felt hungry, fiber and other undigested matter remained in the gut. As a result, there was little need to worry about caloric intake.

However, many people today prefer soft foods that require little chewing and have become overly reliant on refined carbohydrates and UPFs. These diets are low in nutrients and fiber, making them easy to digest, allowing the body to absorb large amounts of energy with minimal effort.

Moreover, once all the food is fully digested in the intestines, a signal that “there is no food” might be sent to the brain.

Such dietary habits were likely rare, if not nonexistent, in human history—at least until around 1970. It is not an overstatement to say that the sharp rise in being overweight, obesity, and many lifestyle-related diseases coincided with the rapid industrialization of food processing in the 1970’s and 80’s.

<References>

[1]Katz DL, Meller S. Can we say what diet is best for health? Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:83-103.

[2]Monteiro CA et al. NOVA. The star shines bright. Food classification. Public Health. World Nutr. J. 2016, 7, 28–38.

[3]Monteiro CA et al. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Jan;21(1):5-17.

[4]Nardocci M et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2019 Feb;110(1):4-14.

[5]Fiolet T et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018 Feb 14;360:k322.

[6]Elizabeth L et al. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 30;12(7):1955.

[7]Juul F et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2018 Jul;120(1):90-100.

[8]Ultra-processed food and drink products in Latin America: trends, impact on obesity, policy implications. Pan American Health Organization, Washington (DC) (2013)

[9]Canella DS et al. Ultra-processed food products and obesity in Brazilian households (2008-2009). PLoS One. 2014 Mar 25;9(3):e92752.

[10]Rauber F et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and indicators of obesity in the United Kingdom population (2008-2016). PLoS One. 2020 May 1;15(5):e0232676.

[11]Mendonça RD et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016 Nov;104(5):1433-1440.

[12]Liu J et al. Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods and Diet Quality Among U.S. Children and Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2022 Feb;62(2):252-264.

[13]Bonaccio M et al. Association between Late-Eating Pattern and Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food among Italian Adults: Findings from the INHES Study. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 20;15(6):1497.

[14]Beunza JJ et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet, long-term weight change, and incident overweight or obesity: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Dec;92(6):1484-93.

[15]Barr SB, Wright JC. Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food Nutr Res. 2010 Jul 2;54.

[16]Fereidoon Shahidi. Nutraceuticals and functional foods: Whole versus processed foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology, Volume 20, Issue 9, 2009, Pages 376-387.

[17]Secor SM. Specific dynamic action: a review of the postprandial metabolic response. J Comp Physiol B. 2009 Jan;179(1):1-56.

[18]Roberts SB. High-glycemic index foods, hunger, and obesity: is there a connection? Nutr Rev. 2000 Jun;58(6):163-9.

[19]Hall KD et al. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab. 2019 Jul 2;30(1):67-77.e3.

2024.10.14

The Increasingly Important "Set-Point" Theory of Body Weight: What are the Environmental and Behavioral Factors?

-

Contents

- Advances in understanding “set-point” theory

- Problems with the set-point model

- Environmental and behavioral factors influencing weight set-point

- Why intestinal starvation increases one’s set-point weight

<How to prove my theory>

- Advances in understanding “set-point” theory

As I've explained in previous blog posts, I believe that each person has an individual “set-point” for their weight, and that understanding how this set-point increases is the key to addressing the issue of obesity.

This time, I would like to share my thoughts on recent advances in research regarding the set-point theory of body weight, as well as the environmental and behavioral factors that influence it.

1. Advances in understanding “set-point” theory

<Obesity and weight loss attempts>

♦A fat person who insists that a lean friend has consistently eaten more than the fat person does, may well be telling the truth.(*snip*)

The group of obese patients who are greatly in need of our understanding are those who keep to a calorie intake of perhaps 1000 kcal per day, yet lose less than one kg per week. There is no doubt whatsoever that such people exist, and can be studied in a metabolic ward under conditions where 'cheating' is virtually impossible without being detected. Usually these are middle-aged women who have been perhaps 40 kg overweight, and who have already lost about 20 kg. They are often depressed, hypothermic, and have a low metabolic rate. The nature of this metabolic adaptation to a low calorie diet is not known (as of 1973), but it is a phenomenon which has been known since before 1920. [1](J S Garrow, 1973)

♦For obese individuals, a certain amount of weight loss is possible through a range of treatments, but long-term sustainability of lost weight is much more challenging, and in most cases, the weight is regained [2]. In a meta-analysis of 29 long-term weight loss studies, more than half of the lost weight was regained within two years, and by five years, more than 80% of lost weight was regained [3,4].

In addition, studies of those who are successful at sustained weight loss indicate that the maintenance of a reduced degree of body fatness will probably require close attention to energy intake and expenditure, perhaps for life[5].

<Metabolic values of obese individuals>

♦The hypometabolic thesis had fallen out of favor by 1930, when more accurate calculations of body-surface area indicated that the metabolic rates of obese individuals were normal[6].

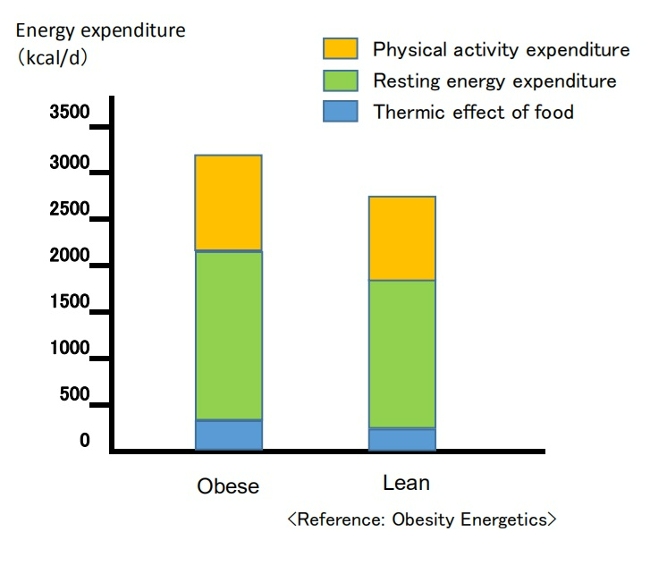

♦Total energy expenditure (TEE) in a day consists of three components: diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT), physical activity energy expenditure (PAEE), and resting energy expenditure (REE). When comparing a model case of men with an average weight of 100 kg and 70 kg, the man weighing 100 kg has a higher TEE[7] .

(Breakdown of energy expenditure in average 100-kg and 70-kg men)

Contrary to popular belief, people with obesity generally have a higher absolute REE compared to leaner subjects.This is because obesity increases both body fat and metabolically active fat-free mass[7,8].

PAEE can be subdivided into "voluntary exercise" and “activities of daily living.” Despite typically engaging in less physical activity, obese individuals often have a daily energy cost for physical activity similar to that of non-obese individuals since PAEE is proportional to body weight [7,9]. Additionally, due to a greater food intake, their DIT also tends to be higher [7].

<Dynamic changes in energy expenditure>

♦Obesity prevention is often erroneously described as a simple bookkeeping matter of balancing caloric intake and expenditure [10].

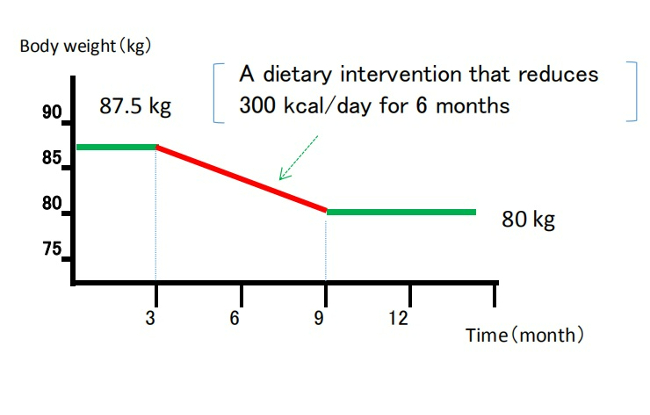

In this model, energy intake and expenditure are considered independent parameters determined solely by behavior. It is assumed that an obese person can steadily lose weight by eating less and/or moving more at a rate of one pound for every 3,500 kcal (or one kg for every 7,200 kcal) of accumulated dietary caloric deficit [7,11]. This view has been referred to as a “static model” of weight-loss, but it has been shown to be physiologically impossible [7,12].

(Static model of weight loss)

(Despite being recognized as overly simplistic, the 3,500 kcal rule continues to appear in scientific literature and has been cited in over 35,000 educational weight-loss websites as of 2013.) [12,13]

♦It is now understood that energy intake and expenditure are interdependent variables, influenced by each other and by homeostatic signals triggered by changes in body weight [7,14].

Attempts to alter energy balance through diet or exercise are countered by physiological adaptations that resist weight loss [7].

<Set-point theory of body weight>

♦In recent years, the influence of homeostatic control has been recognized, and there is growing evidence that the body employs physiological mechanisms to manipulate energy balance and maintain body weight at a genetically and environmentally determined "set-point."[12]

In 1953, Kennedy proposed that body fat storage is regulated [15]. In 1982, nutritional researchers William Bennett and Joel Gurin expanded on Kennedy's concept when they developed the set-point theory [16]. The model has been widely adopted, and strengthened particularly after the discovery of leptin in the 1990’s [7,12].

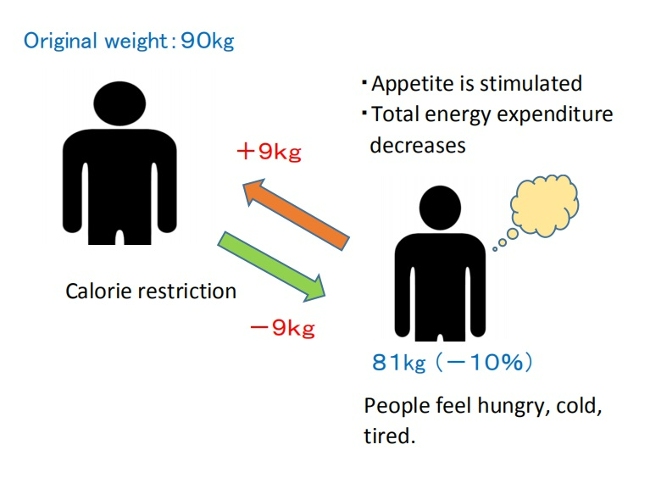

When an individual loses weight, the body significantly reduces energy expenditure to a degree that is often greater than predicted based on changes in body composition or the thermic effect of food. It also causes an increase in appetite through hormonal regulation and alters food preferences through behavioral changes, to drive the body weight back toward its set-point range[7,16].

( Set-point model of weight loss)

♦Weight-loss studies have shown that the magnitude of fat stores in the body is protected by mechanisms mediated by the central nervous system, which adjust energy intake (EI) and expenditure (EE) via signals from adipose tissue, the gastrointestinal tract, and endocrine tissue to maintain homeostasis, and resist weight change (set-point model)[12,17].

♦The body's protective metabolic mechanism that attempts to preserve energy stores during an energy crisis is known as adaptive thermogenesis (AT) or metabolic adaption[7,12].

AT is defined as the underfeeding-associated fall in resting energy expenditure (REE), independent of changes in body composition[12].

♦Maintenance of a 10% or greater reduction in body weight in lean or obese individuals is accompanied by about 20 to 25% decline in 24-hour energy expenditure. This reduction in weight maintenance calories is 10 to 15% lower than what is predicted based solely on alterations (/changes) in fat and lean mass [17,18].

Since obese individuals also display these compensatory metabolic adjustments in response to dietary restriction, obesity may be considered a natural physiological state for some people. Experimental studies on obesity in animals similarly suggest a view of obesity as a condition of body energy regulation at an elevated set-point [19].

♦A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies investigating adaptive thermogenesis (AT) by comparing formerly obese subjects who had lost weight with BMI-matched subjects who were never obese, reported a 3–5 % lower resting energy expenditure (REE) in formerly obese subjects compared to never obese controls[20].

This effect means, for example, that if an obese woman reduced her weight from 100kg to 70kg, she would have to consume fewer calories to remain at 70kg than a woman who had consistently weighed 70kg[6]. Similar results have been confirmed in animal experiments involving obese and normal-weight rats.

This suggests that the frequent claim made by obese people that they eat the same or less than their lean friends but lose no weight, must be given more credence than it is ordinarily accorded[19].

♦On the other hand, as shown in overfeeding experiments on prisoners in Vermont in the 1960’s (Doctor Ethan Sims), weight gain due to temporary overeating also triggers compensatory mechanisms that bring body weight back into a set-point range.

However, some researchers point out that these may be weaker than those protecting weight loss. This asymmetry could be due to the evolutionary advantage of storing fat to survive during periods of caloric restriction, such as prolonged starvation [16,17].

♦In addition, hyperphagia (overeating) has been demonstrated following experimental semi-starvation and short-term underfeeding, which is probably the result of homeostatic signals resulting from the loss of both body fat and lean tissue [7,21].

♦This theory also suggests that a person's set-point for body weight is established early in life and remains relatively stable unless altered by specific conditions. However, the set-point may change throughout one’s life due to factors such as marriage, childbirth, menopause, aging, and disease [16].

On the other hand, the set-point theory remains a theory because all the molecular mechanisms involved in set-point regulation have not been elucidated, and some researchers may consider this theory to be overly simplistic[16].

2. Problems with the set-point model

However, some researchers have pointed out problems with the set-point model of regulation.

If such a powerful biological feedback system regulating the state of our body fat exists, then why do many individuals in most Western countries gain weight throughout majority of their lives? In particular, they argue that this model cannot explain the increasing prevalence of obesity that has been observed in many societies worldwide since the 1970’s[22].

In response, some researchers argue that while metabolic resistance to sustaining a reduced body weight is strong, metabolic resistance to sustained increased adiposity may not be physiologically long-lasting. The steadily increasing prevalence of obesity in humans also suggests that the state of body fat is facilitated more vigorously than losing weight[17,23].

Animal studies in mice demonstrated increased energy expenditure and increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) tone during the first 3-4 weeks of consuming a high-fat diet, while these changes were no longer evident after a few months of high-fat diet consumption[17,24].

Another animal study in mice reported that long-term consumption of palatable, high-energy diets such as potato chips, cheese crackers, cookies, etc., caused irreversible weight gain, suggesting an increase in the set-point weight[19,25]. This effect is believed to be due to the increases in the number of fat cell[19,26].

■These explanations may sound reasonable at first, but in my opinion, this is no longer a "set-point" and it fails to explain why the body stubbornly shows metabolic resistance to maintaining weight loss, even at a higher set-point weight.

When applied to humans, not everyone who frequently consumes high-calorie foods becomes obese. This brings up several contradictions, such as:

(1)Why is obesity more prevalent among the lower-income groups in Western societies[22,27] and relatively wealthier groups in developing societies?[28];

(2)The coexistence of undernutrition and obesity in poor populations, observed globally since the 1950’s[29];

(3) Why do some people gain weight after environmental changes such as entering college, getting married, having children, or moving from Asia to Western countries?[22]

As I have mentioned repeatedly in this blog, I believe that an increase in set-point for body weight is due to inducing intestinal starvation, and that I can explain all these contradictions.

In the following section, I will explain that more specifically.

3. Environmental and behavioral factors influencing weight set-point

In 2012, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) designated obesity as a chronic disease. One of the rationale for that designation is that, like other chronic diseases, the pathophysiology of obesity is complex, involving interactions of genetic, biological, environmental, and behavioral factors[30].

Some researchers interested in the body weight set-point theory argue that understanding how genes and the environment interact to regulate the set-point is essential to determining whether obesity, as a chronic disease, can be cured. However, they struggle to explain the many significant environmental and social influences[22].

■ I also believe that the set-point of body weight changes due to the interaction between (1) genetic and biological factors, and (2) environmental and behavioral factors, but this time, I will mainly discuss (2) in this article.

When considering changes in living environment since the 1970’s, most researchers blame the rise in obesity on the increased availability of high-calorie foods and a decrease in physical activity as society became more affluent. In other words, they believe that a positive energy balance is necessary for weight gain.

However, paradoxically, the fact that the increasing prevalence of obesity coincides with an increase in weight-loss attempts[31] suggests that our understanding of energy balance may be flawed[12].

As suggested by overfeeding experiments, “temporary weight gain from overeating” and “irreversible weight gain occurring over many years ” are different. In my view, obesity as a chronic disease arises rather from signals of negative energy balance or "food scarcity" in the body, as in the cases where people gain more weight than before after starvation or dieting.

[Related article]

The Overfeeding Study Suggests That "Overeating" Is Not the Cause of Obesity

■Despite its impact on our bodies due to changes in our living environments since the 1970’s, "intestinal starvation" remains unrecognized.

Intestinal starvation refers to a state where everything consumed is fully digested throughout the entire intestinal tract, and it can occur in today's affluent developed countries, developing countries, or even among the poor. When there is little or no fiber and everything has been digested, our bodies perceive it as having "no food."

【Related Article】

The Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past

Perhaps in many parts of the world before 1970, even if people went a whole day without eating until their next meal, there were likely still undigested substances like fiber and tough plant cell walls left in their intestines. However, in today’s society, with its abundance of easily digestible, refined carbohydrates, processed foods, and fast food, intestinal starvation can occur in as little as eight to ten hours, depending on eating habits.

Intestinal starvation is more likely to occur with frequent consumption of easily digestible refined carbohydrates (bread, noodles, rice, etc.), industrially processed meat or fish products, fast food, and snacks, etc., combined with a lack of vegetables and long periods of prolonged hunger (such as skipping breakfast, late-night meals, or irregular eating habits).

【Related Article】

■In the animal experiments on rats described in section 2 above, it was reported that consuming a "high-energy diet" for 90 days led to irreversible weight gain, suggesting an increase in the set-point. However, the "fattening” diet used in this experiment (Rolls et al., 1980) primarily consisted of highly palatable items like potato chips, cheese crackers, and cookies sold in supermarkets. Those foods contained 47.5% industrially processed refined carbohydrates (fat: 42%, protein: 10.5%) on an energy basis[25]. Moreover, rats only eat when they’re hungry, and they are capable of eating the same food repeatedly.

In contrast, the “chow” fed to the control rats may have been made from ingredients like ground wheat, ground corn, soybean meal, and fish meal, etc. In other words, just as our diets from over fifty years ago, it likely contained a high amount of indigestible components, such as fiber and tough plant cell walls.

Therefore, I question the conclusion that highly palatable "high-energy diets" alone caused the irreversible weight gain.

4. Why intestinal starvation increases one’s set-point weight

Below, I will explain the mechanism by which the set- point for body weight increases due to the induction of intestinal starvation. While some of it involves speculation, it is based on events that have happened to me several times. You may not believe it, but at least for me, it is 100% accurate.

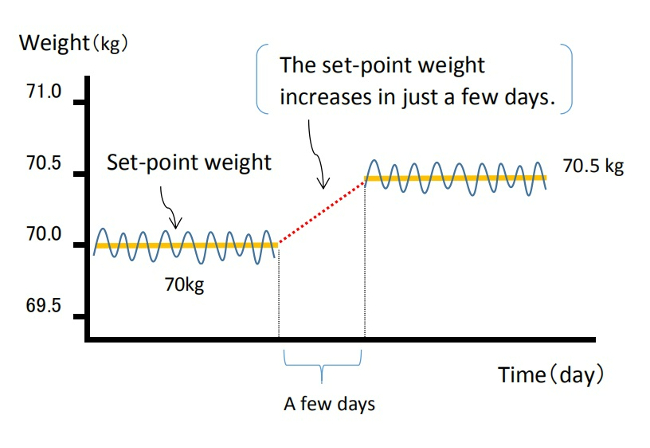

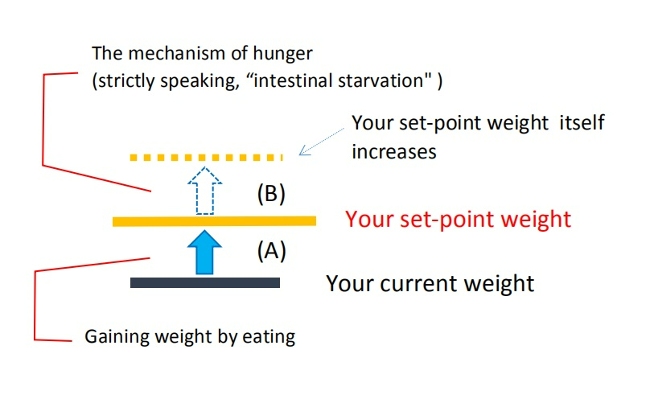

■Let's assume there is a man who has maintained a weight of 70 kg for many years. Even though his weight may fluctuate slightly during busy periods or after overeating, his weight revolves around 70 kg, so his set-point would be considered 70 kg.

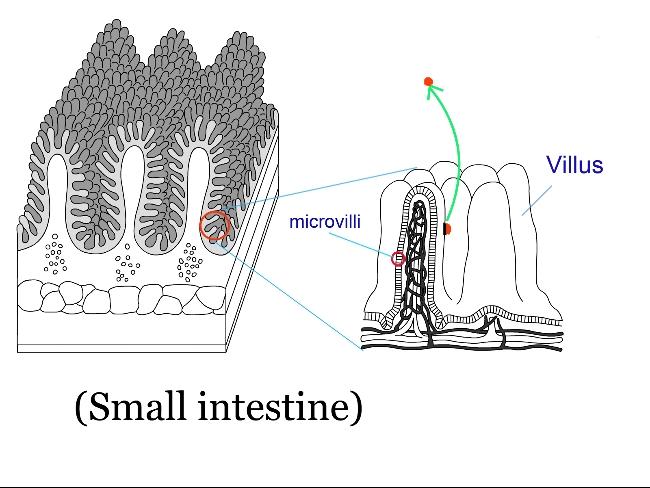

When intestinal starvation occurs, a signal that 'there is no food' is transmitted from the intestines (or small intestine) to the brain.

As a result, the body tries to absorb more nutrients, causing microscopic substances attached to the villi (or microvilli) in the small intestine to detach (Figure 1), thereby increasing the surface area for absorption and raising the absolute absorption ability.

In other words, I believe that weight gain, at least to some extent, involves not only an increase in body fat but also lean tissue such as muscle.

(Fig. 1 )

(Normally, a few undigested fiber or fats may remain, but when all food is perfectly digested, 5 to 10 kg of weight gain over a short period is possible.)

As a result, I believe the weight balancing point (the set-point) increases and reaches equilibrium within just a few days (Figure 2).

Weight gain does not occur from the gradual accumulation of excess calories each day, but rather in one sudden jump, possibly 0.3kg or 0.5g.

When dieting, the set-point can unknowingly rise, so you may gain a few pounds more than before once the diet ends.

(Fig. 2 )

Once the body’s balance point rises, it becomes harder to lose weight because the overall absorption ability has increased. As mentioned in reference in section 1 , I agree with the idea that obesity is a “state of energy regulation at a higher set-point,” and is "a natural physiological condition" for obese individuals.

For more details, please refer to the article below.

【Related Article】

Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

<How to prove my theory>

It may be difficult to determine the exact cause when someone gains a few kg in a year, meaning their highest weight ever. However, I believe that, even with reduced calorie and carbohydrate intake from the meals I provide, it is possible to significantly increase a person's weight (by around 5 to 10 kg) within a few months, setting a new high set-point weight. By observing the data before and after, I think it is possible to investigate what changes have occurred inside the body.

<References>

[1]Garrow JS. Diet and obesity. Proc R Soc Med. 1973 Jul;66(7):642-4. PMID: 4741395; PMCID: PMC1645095.

[2]Wu T, Gao X, Chen M, van Dam RM. Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009;10(3):313–323.

[3] Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Jan;102(1):183-197.

[4]Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001 Nov;74(5):579-84.

[5]Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323-41.

[6]Jou C. The biology and genetics of obesity--a century of inquiries. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 15;370(20):1874-7.

[7]Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition. Gastroenterology. 2017 May;152(7):1718-1727.e3.

[8]Nelson KM, Weinsier RL, Long CL, et al. Prediction of resting energy expenditure from fat-free mass and fat mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:848–856.

[9]Westerterp KR. Physical activity, food intake, and body weight regulation: insights from doubly labeled water studies. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:148–154.

[10] Levine DI. The curious history of the calorie in U.S. policy: a tradition of unfulfilled promises. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:125–129.

[11] Hall KD, Chow CC. Why is the 3500 kcal per pound weight loss rule wrong? Int J Obes (Lond). 2013 Dec;37(12):1614.

[12] Egan AM, Collins AL. Dynamic changes in energy expenditure in response to underfeeding: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2022 May;81(2):199-212. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121003669. Epub 2021 Oct 4. PMID: 35103583.

[13]Thomas DM, Martin CK, Lettieri S et al. (2013) Can a weight loss of one pound a week be achieved with a 3500-kcal deficit? Commentary on a commonly accepted rule. In Int J Obes 37, 1611–1613.)

[14]Hall KD, Heymsfield SB, Kemnitz JW et al. Energy balance and its components: implications for body weight regulation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Apr;95(4):989-94.

[15]KENNEDY GC. The role of depot fat in the hypothalamic control of food intake in the rat. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1953 Jan 15;140(901):578-96.

[16] Ganipisetti VM, Bollimunta P. Obesity and Set-Point Theory. 2023 Apr 25. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 37276312.

[17] Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010 Oct;34 Suppl 1(0 1):S47-55.

[18] Leibel R, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Eng J Med. 1995;332:621–28.

[19] Richard E. Keesey, Matt D. Hirvonen, Body Weight Set-Points: Determination and Adjustment, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 127, Issue 9, 1997, Pages 1875S-1883S, ISSN 0022-3166.

[20]Astrup A, Gøtzsche PC, van de Werken K, et al. Meta-analysis of resting metabolic rate in formerly obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Jun;69(6):1117-22.

[21] Dulloo AG, Jacquet J, Girardier L. Poststarvation hyperphagia and body fat overshooting in humans: a role for feedback signals from lean and fat tissues. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:717–723.

[22]Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. Set points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity. Dis Model Mech. 2011 Nov;4(6):733-45.

[23] Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, et al. Is the energy homeostasis system inherently biased toward weight gain? Diabetes. 2003 Feb;52(2):232-8.

[24] Corbett SW, Stern JS, Keesey RE. Energy expenditure in rats with diet-induced obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986 Aug;44(2):173-80.

[25] Rolls B.J., Rowe E.A., Turner R.C. Persistent obesity in rats following a period of consumption of a mixed high energy diet. J Physiol. 1980 Jan;298:415-27.

[26]Faust I.M., Johnson P.R., Stern J.S., Hirsch J. Diet-induced adipocyte number increase in adult rats: a new model of obesity. Am. J. Physiol., 235 (1978), pp. E279-E286

[27] Dykes J et al. Socioeconomic gradient in body size and obesity among women: the role of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger in the Whitehall II study. International Journal of Obesity 2004 Feb,:262-68.

[28] Poskitt EM. Countries in transition: underweight to obesity non-stop? Ann Trop Paediatr. 2009 Mar;29(1):1-11.

[29] Gary Taubes. 2011. Why we get fat. New York: Anchor Books, Pages 31-40.

[30]Garvey WT. Is Obesity or Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease Curable: The Set Point Theory, the Environment, and Second-Generation Medications. Endocr Pract. 2022 Feb;28(2):214-222.

[31]Montani JP, Schutz Y, Dulloo AG. Dieting and weight cycling as risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases: who is really at risk? Obes Rev. 2015 Feb;16 Suppl 1:7-18.

2022.10.10

Does Obesity Run in the Family or Is It Due to the Living Environment?

Contents

- What was the relationship of weight between adoptees and adoptive parents?

- What was the weight of the twins raised apart?

- What do we consider a change in environment?: My thoughts

- Will the shape of your body from childhood continue?

<The bottom line>

Is obesity inherited from parents?

Let us recall our classmates in elementary school. To some extent, we can imagine, if not one hundred percent, that if the parents are thin, their children are often thin, and if the parents are fat, their children are often fat.

The question here is whether this is due to genetics or due to the living environment. Here is one such study I’d like to introduce.

1. What was the relationship of weight between adoptees and adoptive parents?

"Obese children often have obese siblings. Obese children become obese adults. Obese adults go on to have obese children. Childhood obesity is associated with a 200 percent to 400 percent increased risk of adult obesity. This is an undeniable fact. (*snip*)

Families share genetic characteristics that may lead to obesity. However, obesity has become rampant only since the 1970s. Our genes could not have changed within such a short time. Genetics can explain much of the inter-individual risk of obesity, but not why entire populations become obese.

Nonetheless, families live in the same environment, eat similar foods at similar times and have similar attitudes. Families often share cars, live in the same physical space and will be exposed to the same chemicals that may cause obesity–so-called chemical obesogens. For these reasons, many consider the current environment the major cause of obesity.

Conventional calorie-based theories of obesity place the blame squarely on this “toxic" environment that encourages eating and discourages physical exertion. Dietary and lifestyle habits have changed considerably since the 1970s (e.g. car, television, computer, fast food, high-calorie food, sugar, etc.).

Therefore, most modern theories of obesity discount the importance of genetic factors, believing instead that consumption of excess calories leads to obesity. Eating and moving are voluntary behaviors, after all, with little genetic input.

So-exactly how much of a role does genetics play in human obesity?"

(Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Page 21-2.)

"The classic method for determining the relative impact of genetic versus environmental factors is to study adoptive families, thereby removing genetics from the equation.(*snip*)

Dr. Albert J. Stunkard performed some of the classic genetic studies of obesity. Data about biological parents is often incomplete, confidential and not easily accessible by researchers. Fortunately, Denmark has maintained a relatively complete registry of adoptions, with information on both sets of parents.

Studying a sample of 540 Danish adult adoptees, Dr. Stunkard compared them to both their adoptive and biological parents.

If environmental factors were most important, then adoptees should resemble their adoptive parents. If genetic factors were most important, the adoptees should resemble their biological parents.

No relationship whatsoever was discovered between the weight of the adoptive parents and the adoptees.(*snip*)

Comparing adoptees to their biological parents yielded a considerably different result. Here there was a strong, consistent correlation between their weights.

The biological parents had very little or nothing to do with raising these children, or teaching them nutritional values or attitudes toward exercise. Yet the tendency toward obesity followed them like ducklings. When you took a child away from obese parents and placed them into a "thin" household, the child still became obese.(*snip*)

This finding was a considerable shock. Standard calorie-based theories blame environmental factors and human behaviors for obesity. Environmental cues such as dietary habits, fast food, junk food, candy intake, lack of exercise, number of cars, and lack of playgrounds and organized sports are believed crucial in the development of obesity. But they play virtually no role."

(Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 22-3.)

2. What was the weight of the twins raised apart?

"Studying identical twins raised apart is another classic strategy to distinguish environmental and genetic factors. Identical twins share identical genetic material, and fraternal twins share 25 percent of their genes.

In 1991, Dr. Stunkard examined sets of fraternal and identical twins in both conditions of being reared apart and reared together. Comparison of their weights would determine the effect of the different environments.

The results sent a shockwave through the obesity-research community. Approximately 70 percent of the variance in obesity is familial.(*snip*)

However, it is immediately clear that inheritance cannot be the sole factor leading to the obesity epidemic.

The incidence of obesity has been relatively stable through the decades. Most of the obesity epidemic materialized within a single generation. Our genes have not changed in that time span.

How can we explain this seeming contradiction?"

(Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 23-4.)

3. What do we consider a change in environment? : My thoughts

I think this is a very interesting study because it compared data from biological parents and adoptive parents.

However, can we assert from the results of this one alone that the influence of genetics was much greater and environmental factors were much less significant?

I believe, as Doctor Fung mentions, the rapid increase in obesity in recent years (since about 1970) has much to do with changes in our living environment (what we eat, irregular lifestyle,etc.),not the genes.

Even those who were slim in their youth may gain five or ten kilos in a short period of time at a certain age, triggered by something (living alone, marriage, parenting, stress from work, etc.). Some people put on weight every time they try dieting to lose weight.

In other words, many of us, in our hearts, have probably noticed that changes in eating habits or our living environment can change our body shape.

■What is the "change in environment" that causes a change in weight here?

The study considers a child living with adoptive parents or twins raised separately to be a "change in living environment," but I think there is a problem with this study.

If a family can afford to take in a child as adoptive parents, don't they have some money to spare and feed their adoptee a somewhat balanced diet three times a day?

Although what they eat and caloric intake may differ from family to family, those changes are not necessarily "environmental changes" that cause changes in weight. Just because the adoptive parents are thin does not mean that adoptees will become thin even if they eat the same diet.

On the contrary, I believe that a fundamental increase in weight and body shape occurs when one’s set-point weight itself goes up, which is induced by intestinal starvation.

And since at least three (+one) factors are required to induce intestinal starvation, living with adoptive parents alone does not necessarily alter one’s set-point weight.

[Related article]

In Japan over the past few decades, our traditional eating habits have been declining. Instead, Westernized eating and diverse work styles have become more prevalent.

Amid these changes, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced when unbalanced diets (high in easily digestible carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, and with a lack of vegetables, etc.) combines with irregular lifestyle habits (skipping breakfast, eating late at night, etc.).

This is what I would like to call the "environmental factors and human behaviors" for the recent obesity epidemic, and while genetic factors are, of course, undeniable, I believe that environmental factors are quite significant.

4. Will the shape of your body from childhood continue?

One thing to note here is that the body shape in childhood (say, around three to five years old) tends to continue into adulthood.

When I think back to my classmates in first and second grade, the girls and boys who were fat (although they were not big eaters) often have a similar body shape even decades later.

From my theory, that means that their set-point weight has not changed, and in this study, if there are no environmental factors that cause changes in their set-point for body weight, then wouldn't the body shape from childhood basically continue?

But, I’m simply wondering what the childhood body shape is due to? Whether it is genetic factors or the way food is prepared during childhood-including weaning-is a question that remains unanswered.

The bottom line

(1) In a study regarding adoptive families and examining how genetic and environmental factors influence being overweight, no correlation was found between the weight of adoptive parents and that of their adoptees. On the other hand, when the adoptees were compared to their biological parents, there was a consistent correlation between the weight of both.

A study of twins raised separately also concluded that "genetic influences are far more significant.”

(2) Many researchers had previously blamed "environmental factors and individual behavior” for the recent obesity epidemic, but this study concluded that genetics had far more impact than environmental factors.

However, I find this study problematic. The fact of children living with adoptive parents or twins raised separately is not necessarily an environmental factor that causes changes in weight.

(3) Of course, I do not think we can ignore the genetic factor, but I believe that the recent obesity epidemic is caused by a combination of what we eat-westernized diets, refined carbohydrates, processed foods, etc.-plus lifestyle changes.

A major change in weight and body shape occurs when one’s set-point weight goes up, which is induced by intestinal starvation.

(4) If there is no significant change in one's set-point weight, I think the body shape from childhood is expected to continue. However, I 'm uncertain what determines childhood body shape, whether it is heredity or the way food is prepared during childhood, including weaning.

2022.09.24

Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

Contents

- How has our Japanese diet changed over the past fifty years?

- The Pima tribe who gained weight under rations, not prosperity

- The newer the diet in history, the less fit the body is

<End note>

1.How has our Japanese diet changed over the past fifty years?

I was born in 1970, about fifty years ago. That was when twenty-five years had passed since the end of the World WarⅡ, and Japan was in the midst of its rapid economic growth.

In retrospect, I feel that the food scene was quite different from what it is today. My parents were farmers in the country side of Osaka, growing rice and mushrooms. We also had about twenty chickens to get fresh eggs.

On the dining table in the morning, there was usually rice, miso soup, pickles, traditional stewed vegetables, and half-dried fish. I remember the family eating together.

Of course, we sometimes ate bread, but my father did physical labor, so rice was an essential part of breakfast.

(Typical Japanese breakfast we used to have)

■The 1970s, when the dining scene changed dramatically

I think it was after 1970 that our dining landscape slowly changed. I had not been taken to restaurants much when I was a kid, but fast food restaurants and other restaurant chains opened one after another in all corners of Japan, and many people began to eat Western food.

McDonald's (since 1971), Kentucky Fried Chicken (since 1970) and family restaurants called Skylark (since 1970) were the most famous among them. In 1974, the first convenience stores (called Seven-Eleven) opened in Tokyo, followed by a rapid increase throughout the country. Instant foods such as cup noodles and frozen foods also increased rapidly, reflecting busy social conditions.

Even in the 1970s, school lunches already had bread as their side dish rather than rice (apparently at the behest of GHQ, which ruled after the war), and those of us who had grown accustomed to such a diet began to prefer bread, noodles, and other wheat-based foods even as adults.

Along with this, we liked to eat meat and (ultra-) processed foods rather than fish with bones.

We began to prefer soft foods to fibrous and hard foods, and the traditional vegetable stews that had been commonly eaten became less and less common.

Our lifestyles also changed dramatically. More and more people began to work at desks rather than at physical jobs. Nighttime lifestyles became the norm, and more people didn't even eat breakfast.

It was probably around this time that obesity began to increase in Japan. Nowadays, it is not unusual to see women over one hundred-kilograms on the streets.

(Percentage of adults with a BMI of 25 or higher: In both men and women, it has been increasing since 1980

One might think that increased caloric intake was the cause of being overweight.

However, on a caloric basis, the average daily caloric intake of the population in 1970 was twenty-two-hundred kcal, yet in 2010 it had decreased to eighteen-hundred-fifty kcal. [1]

To explain this in my theory, the modern diet is often low in fiber and tends to favor easily digestible refined carbohydrates, processed meat and fish products, and fast food, etc., which can, in turn, induce a state of intestinal starvation based on how we combine the foods.

In particular, with changes in eating habits, such as having only two meals a day (skipping breakfast or lunch), light lunches, or late dinners, as well as dietary restrictions due to dieting, many people experience long periods of hunger, making intestinal starvation more likely to occur.

2. The Pima tribe who gained weight under rations, not prosperity

As an example of how obesity has increased as old traditional eating habits have declined and became westernized, I would like to cite a Native American tribe known as the Pima, although the situation is slightly different.

This is the second time I quote from Mr. Taubes' "Why We Get Fat," but this part is very important and may be the key to solving the problems of obesity, diabetes, and other diseases.

"Consider a Native American tribe in Arizona known as the Pima. Today the Pima may have the highest incidence of obesity and diabetes in the United States. Their plight is often evoked as an example of what happens when a traditional culture runs afoul of the toxic environment of modern America. (*snip*)

Between 1901 and 1905, two anthropologists(Russell and Hrdlička) independently studied the Pima, and both commented on how fat they were, particularly the women. (*snip)

Through the 1850s, the Pima had been extraordinarily successful hunters and farmers.

By the 1870s, the Pima were living through what they called the “years of famine.”(*snip*) The tribe was still raising what crops it could but was now relying on government rations for day-to-day sustenance.(*snip*)

What makes this observation so remarkable is that the Pima, at the time, had just gone from being among the most affluent Native American tribes to among the poorest.

Whatever made the Pima fat, prosperity and rising incomes had nothing to do with it; rather, the opposite seemed to be the case.

And if the government rations were simply excessive, making the famines a thing of the past, then why would the Pima get fat on the abundant rations and not on the abundant food they'd had prior to the famines? Perhaps the answer lies in the type of food being consumed, a question of quality rather than quantity.(*snip*)

So maybe the culprit was the type of food. The Pima were already eating everything “that enters into the dietary of the white man,” as Hrdlička said. This might have been key.

The Pima diet in 1900 had characteristics very similar to the diets many of us are eating a century later, but not in quantity, in quality."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 19-23.)

[Related article] Wealthy Ones Get Fat? Poor Ones Get Fat?

In terms of food, I believe that Japanese people in 1970 were eating a lot of different kinds of food than today. There were no convenience stores, and the diet was based on mom's home cooking, with a variety of seasonal vegetables and fish.

In contrast, the modern diet is based on easily digestible carbohydrates and processed meat products, and the variety of food ingredients we eat seems to have decreased dramatically.

Many people are normally worried about gaining weight and are dieting, and then they occasionally splurge and eat high-calorie food as a reward. The situation is different, but if we focus on the inside of the intestines, I can say that it is the same as what happened to the Pima population.

3. The newer the diet in history, the less fit the body is

"The idea is that the longer a particular type of food has been part of the human diet, the more beneficial and less harmful it probably is— the better adapted we become to that food.

And if some food is new to human diets, or new in large quantities, it's likely that we haven't yet had time to adapt, and so it's doing us harm. (*snip*)

The obvious question is, what are the “conditions to which presumably we are genetically adapted”? As it turns out, what Donaldson assumed in 1919 is still the conventional wisdom today: our genes were effectively shaped by the two and a half million years during which our ancestors lived as hunters and gatherers prior to the introduction of agriculture twelve thousand years ago."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 163-4.)

I believe what the author tried to get across was that the modern diet of allowing large amounts of carbohydrates is not genetically compatible with our bodies, and that eating meat and its fat may be more compatible and less harmful to us on a genetic level.

I will quote this passage above to explain my intestinal starvation mechanism.

Suppose (and it makes more sense) that God created a genetic blueprint for people to "store body fat" in case they could not find food.

If the state of "no food" (starvation) was recognized when all food was digested in the entire intestinal tract, then during the hunting-and-gathering age and farming age when people ate wild boar meat, nuts, vegetables with tough cell walls, and unrefined grains, etc., their intestines would not have been in a state of complete starvation even if they couldn’t eat anything for a whole day (because of the long intestines).

In contrast, a modern diet high in quickly digested foods —such as refined wheat and rice, starches, processed meat and fish products, and fast food—can, depending on the combination, lead to a state of intestinal starvation in as little as half a day.

I believe it is the entire intestines (or it may be the small intestine only) that makes all the decisions, and it goes to show that inside the gut, many of us are starving more today than in the past.

References:

[1]Yasuo Kagawa(香川靖雄) , Clock Gene Diet (時計遺伝子ダイエット), 2012, Page 15.

End note

People sometimes say, "Japanese food culture is healthy by world standards," but I believe this to be a relic of the past until around the year 2000 at the latest. Now, I feel that traditional Japanese food culture is dying in the average household.

Children who grew up eating fast food are now in their fifties and sixties, and their children are now in their thirties. Thus, in about fifty to sixty years (about two generations), the opportunity to eat traditional foods will have faded away, and the food culture will change greatly.

And, with the shift in diet, it seems like that diseases such as diabetes, kidney disease, heart disease, cancer, and stroke, which were once not as common, are on the rise, just as they are in the Western countries.

2019.06.22

Obesity as a Multifactorial Disease: "Confounding Factors" in Environmental Influences

-

Contents

-

- "Overeating causes obesity" is too simplistic

- Can environmental and behavioral factors be identified?

- Intestinal starvation can be considered a “confounding factor”

<The bottom line>

1. "Overeating causes obesity" is too simplistic

Reuters and the market research firm Ipsos conducted an online poll in the United States in 2012 with 1,143 adults. The poll found that 61% of American adults believed that "personal choices about eating and exercise" were responsible for the obesity epidemic[1,2]. Many Americans still hold the belief that people who become obese lack willpower, overeat, and don't exercise enough[2].

Similarly, in Japan, even news anchors and experts frequently make statements like, "It's only natural to gain weight if you overeat and don’t exercise." This suggests that many Japanese people likely hold the same belief.

However, scientific research indicates that "personal choices" may not account for all cases of obesity[2].

Classical genetic studies based on adoption studies, family studies, twin studies, etc., indicate that about 50–70% of the variance (heritability estimates) in BMI is genetic (Those estimates vary depending on the study design and assessment methods) [3].

(Note: In the following article, I explain that raising children in different home environments does not necessarily constitute “environmental changes” that alter their set-point weight.)

[Related article]

Does Obesity Run in the Family or Is It Due to the Living Environment?

Even today, the heritability of obesity is estimated at 40% to 70%[4].

Some researchers point out that numerous different genes have been found to be involved in food selection, food intake, absorption, metabolism, and energy expenditure including physical activity. When considering interactions between gene-by-gene or gene(s)-by-environment(s), the complexity of the mechanisms underlying weight regulation becomes even greater[3].

In a 1998 report published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), experts at the time described obesity as a complex, multifactorial chronic disease that develops from an interaction between genotype and the environment (Taubes G. 2010. Why we get fat. Page 76).

In 2012, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) also designated obesity as a chronic disease.

This designation was based on two key points : first, like other chronic diseases, the pathophysiology of obesity is complex, involving interactions among genes, biological factors, the environment, and behavior; second, obesity meets the three criteria that constitute a disease as defined by the American Medical Association[5].

2. Can environmental and behavioral factors be identified?

Assuming that human genes as a whole are unlikely to undergo significant changes over a short span of 50 or 100 years, I believe that the global rise in obesity since the 1970’s is largely attributable to environmental and behavioral factors. I would like to explore this in greater detail.

I will quote an interesting description that is relevant to my blog.

“What causes weight gain? Contending theories abound:

・Calories ・Food reward・Food addiction

・Sugar・Sleep deprivation ・Stress

・Refined carbohydrates・Wheat

・Low fiber intake・All carbohydrates

・Genetics・Dietary fat ・Red meat

・Poverty ・All meat・Wealth

・Dairy products・Gut microbiome

・Snacking・Childhood obesity

The various theories fight among themselves, as if they are all mutually exclusive and there is only one true cause of obesity. For example, recent trials that compare a low-calorie to a low-carbohydrate diet assume that if one is correct, the other is not. Most obesity research is conducted in this manner.

This approach is wrong, since these theories all contain some element of truth."

(Jason Fung. 2016. The Obesity Code. Page 70.)

"THE MULTIFACTORIAL NATURE of obesity is the crucial missing link. There is no one single cause of obesity. (*snip*)

What we need is a frame work, a structure, a coherent theory to understand how all its factors fit together. Too often, our current model of obesity assumes that there is only one single true cause, and that all others are pretenders to the throne. Endless debates ensue.

Too many calories cause obesity. No, too many carbohydrates. No,

too much saturated fat. No, too much red meat. No,

too much processed foods. No, too much high fat dairy. No,

too much wheat. No, too much sugar. No,

too much highly palatable foods. No, too much eating out. No

It goes on and on. They are all partially correct. (*snip*)

All diets (e.g., calorie restriction, low-fat, paleo, vegan) work because they all address a different aspect of the disease. But none of them work for very long, because none of them address the totality of the disease.

Without understanding the multifactorial nature of obesity-which is critical -we are doomed to an endless cycle of blame."

(Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 216-217.)

I think the author provides a keen insight into the multifactorial nature of obesity. We must first understand that being overweight is not as simple as "it happens because we overeat," but arises from a complex interplay of various factors.

However, what I want to emphasize is that, based on my intestinal starvation idea, these complex environmental and behavioral factors can be consolidated to some extent, which means that while those factors often blamed as causes of obesity appear intertwined and hard to explain, if we focus on the unseen workings of the intestines, the underlying causes will become much clearer.

3. Intestinal starvation can be considered a “confounding factor”

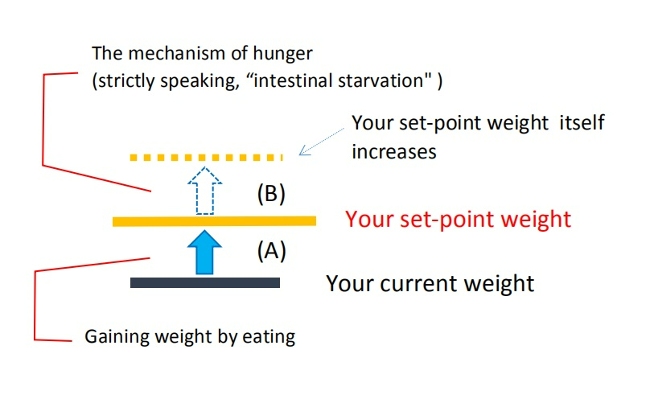

As I’ve already explained, please understand that the phrase “gaining weight” has two meanings.

【related article】

Two Meanings to the Phrase "Gaining Weight"

The mechanism that many people refer to as “get fat by eating a lot” is in the range of (A) in the graph below.

Moreover, I think that most of the Intervention studies on obesity so far have only been comparative studies that involve reducing the intake of calories, regulating the amount of carbs or fat, or increasing exercise, etc. The experiment they are doing is also in the range of (A).

Of course, everyone will lose some weight if they reduce their caloric intake and incorporate exercise, although individual differences may vary.

However, that is not the fundamental way to deal with being overweight, as Dr. Fung mentioned, so regaining weight (the rebound effect) is inevitable if you eat as before.

▽In contrast, when (B) the 'set-point' for body weight goes up by intestinal starvation, there are various interrelated factors.

For instance, it is said that the following affects weight gain:

・Skipping breakfast ・Late dinner ・How many meals you eat

・Refined carbohydrates ・Processed food

・Lack of fiber intake ・Unbalanced diets

These are some of factors that are related to part (B) of the graph.

The important thing here is that each of these factors seems to be linked to weight gain, but there is no causality between each factor and outcome. Rather, they are related to inducing intestinal starvation, and intestinal starvation has a causal relationship with obesity (In this case, some may say intestinal starvation can be the “confounding factor”).

As I’ve already explained in another article, a combination of some of these factors below (from category 1 to 4 of the table) happening simultaneously or overlapping, can cause intestinal starvation, and the occurrence of intestinal starvation may be pinpointed in the unseen workings of the entire intestinal track (or it may be the small intestine only).

[Related article]

Three (+one) Factors to Accelerate “Intestinal Starvation”

The bottom line

(1)Our understanding of how and why obesity occurs is still incomplete. There is a growing societal acceptance of the idea that obesity, like other chronic diseases, has a pathophysiology that is complex and involves interactions among genes, biological factors, environment, and behavior.

(2)Many factors often blamed for causing weight gain—such as refined carbohydrates, processed foods, fats, or skipping breakfast—are discussed only in isolation.

Researchers may be well-versed in their specific areas of research—such as resistant starch, the benefits of eating breakfast, the effects of low-carb diets, hormones, or gut microbiota—but each theory does not necessarily grasp obesity as a whole and often end up being treated in isolation.

What we need now is a framework that shows how each theory is intertwined, and I’d like to believe my theory can contribute to that understanding.

(3)The root cause of being overweight, I believe, lies in the higher set-point weight, which is caused by intestinal starvation. In my opinion, intestinal starvation is a "confounding factor" because it is closely linked to “what we eat” and eating habits (e.g., skipping breakfast, late-night meals, or meal frequency) and also directly influences weight gain (the outcome).

In other words, by focusing on the unseen internal activity of the gut, I believe we can better identify the causes of weight gain.

<References>

[1]Begley S. America's hatred of fat hurts obesity fight. Reuters. May 11, 2012.

[2]Jou C. The biology and genetics of obesity--a century of inquiries. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 15;370(20):1874-7.

[3]Speakman JR, Levitsky DA, Allison DB, et al. Set points, settling points and some alternative models: theoretical options to understand how genes and environments combine to regulate body adiposity. Dis Model Mech. 2011 Nov;4(6):733-45.

[4]McPherson R. Genetic contributors to obesity. Can J Cardiol. 2007 Aug;23 Suppl A(Suppl A):23A-27A.

[5]Garvey WT. Is Obesity or Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease Curable: The Set Point Theory, the Environment, and Second-Generation Medications. Endocr Pract. 2022 Feb;28(2):214-222.