— Topics —

Carbohydrate

2024.02.08

Diabetes (Dysglycemia) is Increasing Despite Decreased Carbohydrate Intake

Contents

- Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and energy intake in Japan(1955-2019)

- Background of the increase in dysglycemia in my opinion

<The bottom line>

If you haven't read the following article yet, please click here to read the original article.

A Low-Carb Diet in Japan:Reducing Carbohydrates Alone is Not the Only Crucial Factor

In this article, I will discuss the causes and background of the relationship between carbohydrate (sugar) intake and the risk of developing diabetes, dysglycemia, etc. in my own way. (The issue of obesity is not discussed in this article.)

1. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and energy intake in Japan(1955-2019)

First, based on the National Health and Nutrition Survey conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the daily intake of carbohydrates, fat, and calories among the Japanese are shown below.

・Carbohydrate intake was 411g in postwar 1955, accounting for 78.1% of total energy intake, but it has been declining since then, reaching 280g in 1995 and 248g (52.1% of total energy intake) in 2019.

・As the economy developed in the postwar period, fat intake sharply increased to 50.1g in 1972 but has remained relatively stable around 55g since 1975. Although there was a slight decrease around the year 2000, annual variations after 1975 are not significant.

・Daily energy intake also increased from 2104 kcal in 1955 to 2287 kcal in 1971. However, there has been a decreasing trend since then, reaching 1903 kcal in 2019.

Nevertheless, the number of diabetes patients and those with blood sugar abnormalities continues to rise. The estimated number of diabetes patients (including those strongly suspected of having diabetes [*1]) has been steadily increasing since the survey began in 1997, from 6.9 million to 10 million in 2016.

If pre-diabetics [*2] with abnormal blood sugar are included, the number surpassed 20 million in 2016 (approximately one in six people). (From the 2016 "National Health and Nutrition Survey" in Japan).

[*1] Individuals with an HbA1c level of 6.5% or higher are considered to be "strongly suspected of having diabetes."

[*2] Individuals with an HbA1c level of 6.0% or higher but less than 6.5% are determined to have a "latent diabetes.”

2. Background of the increase in dysglycemia in my opinion

As evident from the above data, the increase in diabetes patients and individuals with blood sugar abnormalities in Japan cannot be solely explained by carbohydrate or caloric intake.

According to Dr. Yamada, the advocate of the low-carb diet, Japanese people have a weaker ability to secrete insulin than Westerners, and many people can have abnormal blood sugar level even if they are not overweight, but other factors I consider are as follows.

(1) Decline in physical activity

As many experts have pointed out, the increase in diabetes patients and those with blood sugar abnormalities is thought to be partially attributed to a decline in physical activity due to the widespread use of PCs, smartphones, video games, etc. (As for obesity, my theory is that decreased physical activity is not directly related to weight gain or obesity.)

(2) Statistical issues

■The National Health and Nutrition Survey selects about 6,000 households by stratified random sampling from designated unit areas. However, in the 2019 survey, it was reported that cooperative households amounted to 2,836, with 5,900 individuals. Since participation is voluntary, there is a tendency for less cooperation among groups such as men, young people, and singles[1].

■There may be a large gap between the upper and lower limits hidden in the averages. While some people follow an ideally balanced diet, others exhibit poor eating habits. In terms of carbohydrate intake, while some people eat fewer carbs due to dieting, people at high risk of lifestyle-related diseases may be consuming excessive amounts of carbs or have an unbalanced diet that leans toward instant foods, fast foods,etc.

(3) Meal frequency, timing, and more

Not only the quantity and quality of meals but also the frequency, timing, and order of consumption can impact absorption.

Skipping breakfast and having only two meals a day, even with the same amount of carbs at lunch, is said to increase absorption rates, causing a rapid rise in blood sugar levels after lunch.

In contrast, if you consume foods rich in dietary fiber,etc. at breakfast, it can have an impact on the post-lunch and subsequent meal (second meal) blood sugar elevation. This is known as the "second meal effect," as introduced by Dr. Jenkins from the University of Toronto, in 1982.

(4)Dietary balance

■Maintaining a balanced diet is important. Combining carbohydrates with other food groups such as meat, fish, oils, dairy products, and vegetables (fiber) will prolong gastric retention and moderate sugar absorption. This combination may help in controlling the rapid spike in blood sugar levels even with the same amount of carbohydrates. The tendency of many people to reduce fat intake in order to avoid gaining weight may lead to an increase in individuals with abnormal blood glucose levels as well as obesity.

■Since the 1970s, the rise of nationwide fast-food chains and franchise outlets in the food industry has increased opportunities for quick, convenient meals (such as beef bowls, curry, ramen, and hamburgers). These meals often lack vegetables and consist mainly of carbohydrates, potentially leading to a higher risk of blood sugar spikes.

In addition, many Japanese like to eat carbohydrates. Many set menus combine different types of carbohydrates (rice and wheat products), such as ramen noodles and fried rice.

Even if the amount of carbohydrates is small, combinations such as a rice ball and a snack bread (or instant noodles) can easily raise blood glucose levels.

(5) Quality of carbohydrates

■According to statistics from the Ministry of Agriculture in Japan, the per capita annual consumption of rice peaked at 118 kg in 1962 and has since been on a declining trend. By 2020, the consumption had decreased to less than half, reaching 50.8 kg. In addition, examining trends in annual expenditures per household, the amount spent on bread has exceeded the amount spent on rice since 2014.

While the consumption of rice has sharply decreased in recent years, it's crucial to note that there has likely been an increase in the intake of other carbohydrates that raise blood sugar levels, such as bread, sweets, candies, and soft drinks. Thus, relying solely on data related to “carbohydrate intake” may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the situation. (Reference: Japan Low-Carbohydrate Diet Study Group)

■In this context, the glycemic index (GI), which is quantified by blood glucose level and duration after ingesting a food containing 50 g of carbohydrate, is useful.

In addition, there is another indicator called Glycemic Load (GL), which is calculated by multiplying the percentage of carbohydrates in the target food by the GI value.

From the perspective of suppressing a rapid increase in postprandial blood sugar levels, it is important to focus on foods with a low GI/GL value(*3).

While foods such as white bread, refined rice, boiled potatoes, waffles, and french fries,etc are considered to have high GI values, it is worth noting that, foods like unpolished rice, wholegrain bread, beans, and nuts,etc. have low GI values.

(*3) It is said that foods that cause a rapid surge in blood sugar levels, like sugar, but quickly drop, cannot be adequately represented by the GI value.

■It is known that some starches in food, referred to as “resistant starch,” reach the large intestine without being digested. For instance, some starches found in rice, potatoes, and pasta, after being heated and gelatinized, undergo a structural change when cooled, with a portion turning into resistant starch.

Until around the 1970’s to 1980’s when insulated jars were not as common as they are today, it's likely that many people consumed even more resistant starch from "cooled rice" than they do now.

■In the late 1990’s, the National Cancer Center in Japan conducted a five-year follow-up study to investigate the association between carbohydrate intake and the incidence of typeⅡdiabetes. The study targeted approximately 65,000 men and women aged 45 to 75 with no history of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or cancer.

According to the findings, in women, there was a higher incidence of diabetes among those with higher intake of simple carbohydrates (sugar, fructose, etc.) and starches[2].

(6)Evolution of cooking, processed foods, etc

■In recent years, advancements in cooking techniques and the proliferation of processed foods have led to a softening of all types of food, including meat, fish, and vegetables, making them melt in the mouth. In my opinion, such foods, being quickly digested with reduced gastric retention time, may potentially accelerate the absorption of carbohydrates.

■Additionally, many processed foods and sweets often utilize artificial sweeteners. While these sweeteners themselves do not raise blood sugar levels, some experts suggest that their habitual use may impact glycometabolism through changes in taste preferences and alterations in gut microbiota [3][4].

The bottom line

(1) In Japan, since the 1955 statistics, carbohydrate intake has consistently decreased. Caloric intake has also been decreasing over the past fifty years. At least in Japan, the recent increase in diabetes patients and those with blood sugar abnormalities is not solely attributed to carbohydrate or caloric intake.

(2) When it comes to carbohydrates, the way blood sugar levels rise varies. The rapid westernization of the Japanese diet since around 1970 has resulted in a drop in rice consumption in Japan to less than half of its peak level in 1962. Instead, it is thought that the intake of processed wheat products (such as bread, noodles, and snacks) and sugar (sweets and soft drinks), which easily raise blood glucose levels, has increased.

Rice is a grain, and therefore the digestive process should be relatively slower compared to flour-based products, etc. However, even the same type of rice can raise blood glucose levels differently depending on the degree of milling, the cooking method, and the cooling method.

(3) I believe that how blood glucose levels rise is also heavily influenced by dietary balance, the frequency and timing of meals, order of intake, and other dietary habits.

For instance, I suspect that a diet that leans towards easily digestible carbohydrates, frequent intake of sugar, and eating habits such as skipping breakfast or fast eating can increase the frequency of insulin secretion, cause sharp fluctuations in blood sugar levels, and place a burden on the pancreas, even if the carbohydrate intake is not that high.

(4) In order to lower the risk of glucose abnormalities, isn't it important to be aware of not only the carbohydrate content of foods, but also how blood sugar levels rise, such as indicated by the Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL)?

Reducing the intake of high-GI foods and sugars, and opting for low-GI foods (whole grains, protein-rich foods like meat and fish, nuts, dairy), oils, and non-starchy vegetables, is crucial to reduce overall dietary blood sugar elevation.

It's also known that eating regularly three times a day, starting with vegetables, and consuming cooled rice (resistant starch) can contribute to a gentler increase in blood sugar levels throughout the day.

(5) My personal opinion is that a traditional, well-balanced Japanese diet, with rice as the staple, is less likely to increase the risk of obesity and blood sugar abnormalities. Despite the fact that Japan is blessed with seasonal vegetables, seafood, and traditional fermented foods, I feel that in recent years more and more people are eating high GI carbohydrates, meat products, and instant foods, etc.

(For a comprehensive understanding of the effects of low-carb diets, including their impact on obesity causes, please refer to the following article.)

[Related article] A Low-Carb Diet in Japan:Reducing Carbohydrates Alone is Not the Only Crucial Factor

<References>

[1] Japan Society For The Study Of Obesity. Guidelines for the Management of Obesity Disease 2022. Life Science Publishing Co, Dec.2022, Page28.

[2] Kanehara R et al. Association between sugar and starch intakes and type 2 diabetes risk in middle-aged adults in a prospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022 May;76(5):746-755. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-01005-1. Epub 2021 Sep 20. PMID: 34545214.

[3] Pepino MY, Bourne C. Non-nutritive sweeteners, energy balance, and glucose homeostasis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Jul;14(4):391-5. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283468e7e. PMID: 21505330; PMCID: PMC3319034.

[4] Suez, J., Korem, T., Zeevi, D. et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 514, 181–186 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13793

2024.02.07

A Low-Carb Diet in Japan:Reducing Carbohydrates Alone Is Not the Only Crucial Factor

Contents

<Introduction>

- What’s Locabo?

- Summary of the effects of “Locabo"

- The increasing prevalence of diabetes in Japan

- Is controlling insulin the key to weight loss?

- The widespread issue of unbalanced and low-quality diets in Japan

<The bottom line>

<Introduction>

In Japan, since around 2015, the low-carb diet-we call "Locabo" based on the English term "a low-carb"-has been catching on among many people. Japan is traditionally a rice-eating culture, but after World War II, more and more people preferred bread and noodles, and with increasingly westernized diets, many feel that we are gaining weight as well.

This time, I’d like to introduce the Locabo diet in Japan, which is believed to be effective not only for losing weight but also for lowering abnormal blood sugar levels and other lifestyle diseases.

<My stance: I will approach the issues of obesity and blood sugar abnormalities separately.>

Generally, experts advocating for carbohydrate restriction seem to believe that the cause of obesity lies not in excessive caloric intake but in carbohydrates (sugars) that elevate blood sugar levels and stimulate insulin (*1) secretion (the carbohydrate-insulin model).

Additionally, it is believed that prolonged insulin resistance or decreased insulin secretion capacity, can lead to abnormal glucose metabolism, ultimately resulting in the development of lifestyle-related diseases such as diabetes.

In other words, both obesity and symptoms like blood sugar abnormalities are thought to be part of a series of events centered around insulin. However, I believe that obesity is caused by different mechanisms related to carbohydrates, so I would like to explain them separately.

(*1) Insulin is a hormone that lowers the level of glucose in the blood. It's released into the blood by the pancreas when the glucose level goes up. Insulin helps glucose enter the body's cells, where it can be used for energy or stored for future use.

1.What’s Locabo?

"In Japan, the phrase “carbohydrate restriction diet” has been generally used, but the word “restriction” has a somewhat negative image. Therefore, we had to use some different words. We came up with the new word “Locabo” after the English phrase “low-carb” and then it spread throughout Japan.

Locabo is not strict but rather a loose carbohydrate restriction. By definition, the diet tries to keep the carbohydrate intake amount per day to around seventy to one hundred and thirty grams in total, by taking twenty to forty grams per meal, three times a day and also a dessert or sweets up to ten grams.

The difference from a strict carbohydrate restriction is that by eating at least seventy grams of carbohydrates, it avoids an extremely low-carbohydrate condition that results in “Ketosis.”

Also, a strict carbohydrate restriction diet makes food choices very limited, but Locabo has a variety of foods you can enjoy. As long as you keep adjusting carbohydrate intake, you can eat a variety of foods such as meat, fish, cheese, and vegetable dishes without thinking about calories."

[References: Satoru Yamada. The truth of carbohydrate restriction. Gentosha books, Nov. 2015, Page 114]

2. Summary of the effects of “Locabo"

The leading advocate for promoting low-carb diets in Japan is Dr. Satoru Yamada, and summarizing his thoughts, we get the following points:

(1) When blood sugar levels rise due to meals, insulin is secreted from the pancreas. Excessive insulin secretion may potentially lead to weight gain. Japanese individuals have a weaker ability to secrete insulin compared to Westerners, and many people experience blood sugar abnormalities even if they are not overweight. More than half of those who develop typeⅡdiabetes have a BMI less than twenty-five.

(2) The higher the frequency of insulin secretion and the higher the upper limit of blood sugar levels, the greater the burden on the pancreas. Over time, this burden can lead to impaired insulin secretion and the onset of diabetes. Additionally, sharp fluctuations in blood sugar levels may potentially contribute to aging, cell cancerization, cognitive disorders (Alzheimer's), and an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases.

(3) The only factor that raises blood sugar levels is carbohydrates. By adopting a low-carb diet, it is possible to moderate the increase in blood sugar levels.

Nutrients such as proteins, fats, and dietary fiber, aside from carbohydrates, have the ability to suppress a rapid rise in blood sugar.

In other words, fried rice can control the rapid increase in blood sugar more effectively than white rice.

(4) The belief that reducing fat intake is essential for health has been unquestionably accepted in Japan for a long time. However, various data from the twenty-first century has revealed that even if one reduces fat consumption, it may not lead to improvements in blood lipid levels or prevent heart disease and obesity.

While trans fats should be avoided, there is no need to unnecessarily restrict other types of fats. As for the intake of animal fat (saturated fat), such as those found in meat, studies indicate that, when limited to the Japanese population, there is no association with the incidence of myocardial infarction or stroke (data from 2013).

(5) Even with reduced carbohydrate intake, the brain can utilize ketones (produced from fatty acids) as an energy source. In cases of extreme carbohydrate restriction, an accumulation of ketones in the body can lead to a shift in blood acidity, potentially causing a condition known as ketoacidosis. Given the associated risks, it is advisable not to engage in extreme carbohydrate restriction.

(6) Very few individuals can sustain strict caloric limits or a low-fat diet over the long term. A more lenient approach to carbohydrate restriction is easier to adhere to since it doesn't require constant caloric monitoring, and it often yields more favorable results compared to other dietary approaches. It is important to broaden the options for individuals, exploring which dietary approach suits them best.

3.The increasing prevalence of diabetes in Japan

According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey, per capita daily intake of carbohydrates has been consistently decreasing for over sixty years. The daily intake of energy, too, increased until the early 1970’s, but has been on a declining trend since then.

Nevertheless, in recent years, the number of diabetics and latent diabetics with abnormal blood sugar levels continues to rise.

For more detailed data on this trend and other factors I can think of other than carbohydrate intake, please refer to the following article.

【Related article】Diabetes is Increasing Despite Decreased Carbohydrate Intake

4. Is controlling insulin the key to weight loss?

In terms of controlling blood sugar levels, I believe a moderately low-carb diet can be effective. However, what about the issue of obesity?

According to Gary Taubes, the author of "Why We Get Fat," the debate over whether "overeating calories" or "carbohydrates" are the cause of weight gain has been ongoing since the early 1800’s. The reason behind this is that with a low-carb diet, individuals were able to lose weight without worrying about the quantity of other calorie sources such as meat and fats.

This contradicted the calorie theory and faced strong opposition from experts who staunchly believed in it and considered fats harmful to the heart[1], but now it is said that recent intervention studies have demonstrated the significant weight loss effects of a low-carb diet[2], solidifying its position in the field.

Experts who advocate for a low-carb diet seem to believe in the carbohydrate-insulin model, suggesting that carbohydrates cause weight gain by raising blood sugar levels and promoting insulin secretion. According to this model, it is deemed acceptable to consume proteins and fats that do not stimulate insulin secretion, as long as carbohydrates are reduced, in order to compensate for calories. However, I find this explanation to be insufficient.

What I would like to add is as follows: a diet leaning towards easily digestible refined carbohydrates and proteins (processed foods) is rapidly digested. As such a diet continues, you feel hungrier, and intestinal starvation is likely to occer.

The characteristics of carbohydrates (dilution effect, push-out effect) further accelerate the occurrence of intestinal starvation.

(In other words, what is related to intestinal starvation are complex carbohydrates such as starch, rice, and flour, not simple carbohydrates like sugar.)

[Related article]

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates

Therefore, as a countermeasure, we must do the opposite in order to lose weight; not only to reduce carbohydrates to a certain extent but also to increase the intake of foods that take longer to digest (proteins, fats, dairy products, etc.) and foods rich in fiber, so that undigested food will remain abundant in the intestines. (In this regard, the concept of glycemic index [GI] and glycemic load [GL] is very important.)

While advising to consume unlimited amounts of meat and animal fats (saturated fatty acids) doesn't seem accurate, I believe it is important to combine a variety of foods-low-GI carbohydrates, plant-based proteins such as legumes and nuts, unsaturated fatty acids found in fish and plant oils, dairy products, and fibrous vegetables, etc.-to enhance the feeling of fullness.

As a result, the diet may end up resembling a lenient low-carb diet, but my stance is that carbohydrates are not a direct cause of obesity but rather an indirect factor that can induce intestinal starvation. Therefore, I have reservations about strict carbohydrate restrictions such as the ketogenic diet.

Additionally, even if insulin is considered to promote fat storage, I do not believe it is the fundamental cause of obesity.

Some people who advocate a low-carb diet say, "As long as you adjust your insulin secretion, you can eat anything without worrying about calories, even fatty foods, cheese, and meat. And since that's how you lost weight, it was the carbohydrates, not the caloric intake, that was the reason." I don’t think this explanation is correct.

5. The widespread issue of unbalanced and low-quality diets in Japan

In recent years, as the global rise in obesity becomes a significant concern, I believe that for those who tend to gain weight, easily digestible refined carbohydrates are undeniably central factors contributing to weight gain.

However, not everyone gains weight because they eat carbohydrates; factors such as the type of carbohydrates (those with a high GI value), unbalanced diets, and irregular eating habits (such as skipping breakfast or late-night meals) are also associated with the issue.

For instance, focusing solely on caloric and/or carbohydrate "intake," might make it seem like skipping breakfast or opting for simple meals like cup noodles, "snack bread and rice balls," or fast food for lunch is a reasonable choice. It may even appear that not eating vegetables could be somewhat helpful in reducing a few carbs or calories.

However, repeatedly consuming a “low-quality diet” low in fiber and nutrients, rich in carbohydrates, and experiencing recurrent hunger, could potentially increase the risk of developing diabetes and blood sugar abnormalities as well as obesity, don't you think?

While I cannot provide data, to the best of my knowledge, there has been a significant decline in the "quality of meals" among temporary laborers in factories and workplaces, and low-income individuals in Japan in recent years.

When trying to cut down on food expenses, carbohydrates are the cheapest source of calories available, offering a temporary sense of satisfaction.

The bottom line

(1) and (2) are summarized from the contents of "Diabetes is Increasing Despite Decreased Carbohydrate Intake."

(1) The number of diabetes patients in Japan has been steadily increasing since the estimated count began in 1997, rising from 6.9 million to reach 10 million in 2016. Including pre-diabetics with blood sugar abnormalities, the total exceeds 20 million in 2016 (approximately one in six people). Compared to Western populations, Japanese people have a weaker ability to secrete insulin, and over half of those who develop typeⅡdiabetes have a BMI lower than 25.

(2) In Japan, there has been a decreasing trend in caloric and carbohydrate intake for over fifty years. At least in the context of Japan, the rise in obesity, diabetes, and blood sugar abnormalities cannot be solely explained by the amount of caloric and carbohydrate intake alone. Factors such as high glycemic index (GI) foods, sugars, unbalanced diets, and irregular lifestyles including not eating breakfast, may be related to this increase.

(3) Focusing solely on caloric and/or carbohydrate intake might make it seem reasonable to skip breakfast, opt for quick and easy meals like instant noodles or fast food for lunch, and even consider eliminating vegetables.

However, a low-quality diet skewed towards easily digestible carbohydrates and repeated bouts of hunger, may not only increase the risk of developing health issues such as blood sugar abnormalities but also contribute to obesity.

(4) My stance is that the recent increase in (A) the risk of obesity and (B) the prevalence of blood sugar abnormalities is due to the different properties of carbohydrates.

As for (B), the major influence is how a diet containing carbohydrates raises blood glucose levels and its relationship with insulin. In contrast, (A) is associated with easily digestible carbohydrates diluting the food (nutrients) consumed and, under certain conditions, leading to intestinal starvation.

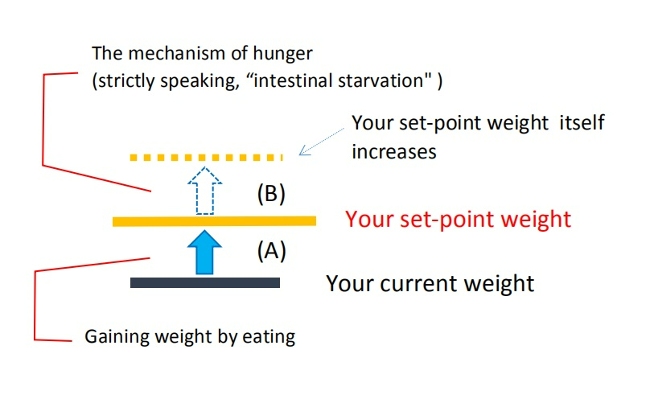

In short, in my theoretical framework, the fundamental issue with obesity is that one’s 'set-point' for body weight goes up through intestinal starvation, and carbohydrates indirectly affect that.

(5) Reducing carbohydrate intake is not the only important factor in decreasing the risk of obesity and blood sugar abnormalities. It is also important to consume low-GI grains, incorporate foods from other food groups (such as meat, fish, vegetables, nuts, dairy, seaweed, etc.) in the diet, and maintain a regular eating schedule (e.g. three meals a day).

All of these practices contribute to slowing down digestion, moderating the speed of absorption, and helping to keep blood glucose levels stable. The concepts of "second meal effect" and "resistant starch" are also important in this regard.

In terms of weight loss, it is crucial to have undigested food consistently remaining in the intestines by consuming more foods that take longer to digest (e.g. proteins, fats) and more fibrous foods.

This approach helps reduce the sensation of hunger, leading to a gradual decrease in absorption rates. Therefore, controlling hunger is, in fact, the key for achieving successful weight loss, in my opinion.

(6) I believe that simple carbohydrates like sugar are significantly related to blood sugar abnormalities. However, the cause of inducing intestinal starvation lies in complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides) such as starch and wheat flour, and not in simple sugars.

<References>

[1] Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor books, 2011, Pages 159-160.

[2] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone books, 2016, Page 100.

2022.12.18

The Atkins Diet: What Were the Long-Term Effects of Weight Loss?

-

Contents

-

- What is the Atkins diet?

- Comparative study of various diets in weight loss

- What were the long-term results of the Atkins diet?

- Why was obesity rare among rice-eating Asians?

- Is the Atkins also ineffective for weight loss?

<The bottom line>

1. What is the Atkins diet?

The Atkins diet is a type of low-carbohydrate diet proposed by cardiologist Robert Atkins that restricts the amount of carbohydrates for energy and instead uses "fat" as an energy source. It is characterized by limiting carbohydrates to twenty to twenty-five grams per day for the first two weeks and then gradually increasing.

According to Dr. Fung, the author of “The Obesity Code,” Dr. Atkins weighed nearly one-hundred kilograms in 1963, and when he began working as a cardiologist in New York City, he needed to lose weight.

However, he couldn’t lose weight successfully on a conventional calorie-restricted diet, so he tried the low-carb diet based on the medical literature, which worked well as advertised, and he recommended it to his patients.

In 1972, he published "Dr. Atkins' Diet Revolution," which quickly became a bestseller.

At the time, it was said that the American Medical Association still considered high fat in the diet to be a cause of heart disease and stroke, and the "low-carb diet," which allowed people to eat as much meat and fat as they wanted, was not accepted.

Despite this, the low-carb diet’s popularity, rekindled in the 1990’s, led to a trend in the Atkins diet. In 2004, twenty-six million Americans said they were on some kind of low-carb diet .

New studies started appearing around 2005, comparing the Atkins diet to other diets that were once considered the standard, and what were the results[1]?

Let's take a look. I would like to express my thoughts on this at the end of this article.

2. Comparative study of various diets in weight loss

"In 2007, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a more detailed study: Four different popular weight plans were compared in a head-to-head trial.

One clear winner emerged-the Atkins diet. The other three diets (Ornish, which has very low fat; the Zone, which balances protein, carbohydrates and fat in a 30:40:20 ratio; and a standard low-fat diet) were fairly similar with regard to weight loss.

However, in comparing the Atkins to the Ornish, it became clear that not only was weight loss better, but so was the entire metabolic profile. Blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugars all improved to a greater extent on Dr. Atkins's diet.

In 2008, the DIRECT (Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial) study reaffirmed once again the superior short-term weight reduction of the Atkins diet. Done in Israel, it compared the Mediterranean, the low-fat and the Atkins diets.

While the Mediterranean diet held its own against the powerful, fat-reducing Atkins diet, the low-fat AHA standard was left choking in the dust–sad, tired and unloved, except by academic physicians."

(Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Pages 100-3.)

3. What were the long-term results of the Atkins diet?

"Longer-term studies of the Atkins diet failed to confirm the much hoped-for benefits.

Dr. Gary Foster from Temple University published two-year results showing that both the low-fat and the Atkins groups had lost but then regained weight at virtually the same rate. (*snip*)

A systematic review of all the dietary trials showed that much of the benefits of a low-carbohydrate approach evaporated after one year.

Greater compliance was supposed to be one of the main benefits of the Atkins approach, since there was no need for calorie counting.

However, following the severe food restrictions of Atkins proved no easier for dieters than conventional calorie counting.

Compliance was equally low in both groups, with upwards of 40 percent abandoning the diet within one year.

In hindsight, this outcome was somewhat predictable. The Atkins diet severely restricted highly indulgent foods such as cakes, cookies, ice cream and other desserts.

These foods are clearly fattening, no matter what diet you believe in. We continue to eat them simply because they are indulgent. (*snip*)The Atkins diet does not allow for this simple fact, and that doomed it to failure.

The first-hand experience of many people confirmed that the Atkins diet was not a lasting one. Millions of people abandoned the Atkins approach, and the New Diet Revolution faded into just another dietary fad. (The company Dr. Atkins founded in 1989 went bankrupt.)

But why? What happened?

One of the founding principles of the low-carbohydrate approach is that dietary carbohydrates increase blood sugars the most. High blood sugars lead to high insulin. High insulin is the key driver of obesity. Those facts seem reasonable enough. What was wrong?"

(Fung J. The Obesity Code. Pages 100-3.)

4. Why was obesity rare among rice-eating Asians?

Experts who advocate low-carbohydrate diets seem to think that carbohydrates cause weight gain because they eventually stimulate insulin secretion.

However, Dr. Fung mentioned that the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis is incomplete. Various problems are cited, but he raised the "paradox of the Asian rice eater" and the "diet of Kitava Island, in Papua New Guinea" as notable examples.

Most Asians have been eating a diet based on refined rice as their staple food for at least the last five decades; a study conducted in the late 1990’s found that carbohydrate intake in China and Japan was similar to or rather, higher than in the U.K. and the U.S.

Nevertheless, until recently, obesity was not a significant problem in both countries.

Also, according to a study conducted by Dr. Staffan Lindeberg in 1989 on the diet of the Kitava islanders, even though they were getting sixty-nine percent of their calories from carbohydrates such as yams, sweet potatoes and cassava, etc., their insulin levels were low and few people were obese[2].

Since Dr. Fung just mentioned the paradox of the Asian rice eater, I would like to mention this.

I am Japanese and was born in 1970, and I think that I should know how our diet has changed in the last five decades, and as a result, how obesity has increased in our society.

(This is explained in more detail in the following blog.)

[Related article] Why Does the Body Perceive That It Is More Starved than in the Past?

In short, I believe that carbohydrates are a contributing cause, but not the quantity itself.

Japan was basically an agrarian society, and rice cultivation has always been important. Until at least 40-50 years ago, I believe most Japanese people had eaten a lot of rice as it is called the staple food, but at the same time, they also ate a lot of fibrous vegetable dishes using roots or stems of plants, fermented soybean product called “natto,” and fish and meat dishes. Rice cakes called “mochi” and Japanese sweets as well.

At least in my family, my father was strict about family members eating meals three times a day at a regular time, every day.

I think the recent increase in the obesity rate in Japan can be explained due to a combination of many factors, including easily digestible carbohydrates such as bread and noodles, unbalanced diets with few vegetables, eating out, instant foods, and irregular life rhythms such as skipping breakfast or late dinners.

What I have seen in my experience is that many young women who go on a diet and then come off, some of them further increase their maximum weight.

(Irregular lifestyle)

I believe that the "three factors plus one" of my intestinal starvation theory can explain how the various factors intertwine, and how weight gain occurs. It's not just the amount of carbs eaten that matter.

5. Is the Atkins also ineffective for weight loss?

The "Do calories make people fat, or carbs?" concept is said to be a debate that has been going on since the 1800’s[3], and I think both are true in some ways, but neither is perfect.

If you reduce the amount of any energy source beyond what your body needs, it’s obvious that you will lose weight in the short term. However, if you go back to your original diet, in the long run, you will also regain the weight you had lost, as various studies have confirmed, and as most people who have been on a diet have probably realized.

The reason for this is that the human body inherently has a homeostatic mechanism that drives it to return to its set point weight. So, the point is that in order to avoid rebounding, you must lower your set-point weight itself.

(For more details, please refer to the article below.)

[Related article] There Are Two Steps to Lose Weight the Right Way

In terms of this rebound in the Atkins diet in section three, I don't think it necessarily means that low-carb diets, including Atkins, are ineffective. I’m positive that it’s the one of the correct ways to lose weight.

However, if we focus too much on blood sugar and insulin levels, we lose sight of another important point.

What I mean is that the key to a low-carb diet, I believe, is not just reducing carbohydrate intake but also increasing foods that are less digestible and take longer to digest, such as fiber-rich foods, meat, fats, and dairy products.

When plenty of undigested food remains in the gastrointestinal tract, it helps to sustain a feeling of fullness and reduces hunger. In the long run, I think this approach can lower absorption rates. In particular, I believe fats and oils in the diet should not be reduced, but rather should be consumed regularly at every meal and even when having snacks.

Considering all of the above, I think that dieticians do not need to ban sweets such as chocolate, candy, ice cream, etc. so strictly. What’s most important is to make the diet sustainable without overburdening yourself, even allowing occasional indulgences in sweets.

The bottom line

(1) In the early 2000’s, the Atkins diet became a huge trend in the U.S., inspired by the low-carb diet that was rekindled in the 1990’s. In the short term, the Atkins method not only helped people lose weight, but it also significantly improved blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose levels.

(2) However, in long-term studies, the subjects rebounded, as seen with low-fat diets. After one year from the end of the study, all the benefits of Atkins diets were gone.

Dr. Fung considered the "carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis" an incomplete theory. Carbohydrate intake itself was not the problem.

(3) My thoughts. If there is no change in your set-point for body weight, rebound can occur if you eat as you used to. In order to lose weight correctly, your set-point weight itself needs to be lowered.

(4) The key to a low-carb diet is not just controlling the amount of insulin released. It’s also important to reduce refined carbohydrates while increasing the intake of fiber-rich foods and those that take longer to digest.

When plenty of undigested food remains in the gastrointestinal tract, it helps sustain a feeling of fullness and alleviates hunger. Over time, I believe this approach can lead to a decrease in absorption rates.

<Reference>

[1] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Greystone Books, 2016, Pages 96-99.

[2] Jason Fung. The Obesity Code. Pages 103-105.

[3] Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 148-162.

2021.10.15

The Combination of Undernutrition and Obesity Among the Poor Can be Possible

Contents

- The case of undernutrition and obesity

- What should we do?

- Being underweight and being overweight can coexist: My thoughts

Most of the parts of this article are citations from a book, but at the end of this article, I will explain how it is related to my experience.

[Related article] → Wealthy Ones Get Fat? Poor Ones Get Fat?

1. The case of undernutrition and obesity

"This combination of obesity and malnutrition or undernutrition (not enough calories) existing in the same populations is something that authorities today talk about as though it were a new phenomenon, but it's not. Here we have malnutrition or undernutrition coexisting with obesity in the same population eighty years ago.

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books. 2011. Page 24.)

(In the mid-1930s, New York City)

In 1934, a young German pediatrician named Hilde Bruch moved to America, settled in New York city, and was 'startled,' as she later wrote, by the number of fat children she saw—'really fat ones, not only in clinics, but on the streets and subways, and in schools. '(*snip*)

But this was New York City in the mid-1930s. This was two decades before the first Kentucky Fried Chicken and McDonald's franchises, when fast food as we know it today was born. This was half a century before supersizing and high-fructose corn syrup.

More to the point, 1934 was the depths of the Great Depression, an era of soup kitchens, bread lines, and unprecedented unemployment.

One in every four workers in the United States was unemployed. Six out of every ten Americans were living in poverty. In New York City, where Bruch and her fellow immigrants were astonished by the adiposity of the local children, one in four children were said to be malnourished. How could this be?(*snip*)

It was hard to avoid, Bruch said, the simple fact that these children had, after all, spent their entire lives trying to eat in moderation and so control their weight, or at least thinking about eating less than they did, and yet they remained obese."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 3, 4.)

(The case of a native American tribe, the Sioux, in 1930's)

"Two researchers from the University of Chicago studied Native American tribe, the Sioux living on the South Dakota Crow Creek Reservation. These Sioux lived in shacks 'unfit for occupancy,' often four to eight family members per room. Fifteen families, with thirty-two children among them, lived “chiefly on bread and coffee.” This was poverty almost beyond our imagination today.

Yet their obesity rates were not much different from what we have today in the midst of our epidemic: 40 percent of the adult women on the reservation, more than a quarter of the men, and 10 percent of the children, according to the University of Chicago report, 'would be termed distinctly fat.'

But the researchers noted another pertinent fact about these Sioux: one-fifth of the adult women, a quarter of the men, and a quarter of the children were 'extremely thin.'

The diets on the reservation, much of which, once again, came from government rations, were deficient in calories, as well as protein and essential vitamins and minerals. The impact of these dietary deficiencies was hard to miss: 'Although no counts were taken, even a casual observer could not fail to note the great prevalence of decayed teeth, of bow legs, and of sore eyes and blindness among these families.'"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 23-4.)

(In the slums of São Paulo, Brazil)

"This is from a 2005 New England Journal of Medicine article, ''A Nutrition Paradox-Underweight and Obesity in Developing Countries,' written by Benjamin Caballero, head of the Center for Human Nutrition at Johns Hopkins University.

Caballero describes his visit to a clinic in the slums of São Paulo, Brazil.

The waiting room, he writes, was 'full of mothers with thin, stunted young children, exhibiting the typical signs of chronic undernutrition.

Their appearance, sadly, would surprise few who visit poor urban areas in the developing world. What might come as a surprise is that many of the mothers holding those undernourished infants were themselves overweight.'(*snip*)

If we believe that these mothers were overweight because they ate too much, and we know the children are thin and stunted because they're not getting enough food, then we're assuming that the mothers were consuming superfluous calories that they could have given to their children to allow them to thrive.

In other words, the mothers are willing to starve their children so that they themselves can overeat. This goes against everything we know about maternal behavior. (*snip*)

Caballero then describes the difficulty that he believed this phenomenon presents: ''The coexistence of underweight and overweight poses a challenge to public health programs, since the aims of programs to reduce undernutrition are obviously in conflict with those for obesity prevention.'

Put simply, if we want to prevent obesity, we have to get people to eat less, but if we want to prevent undernutrition, we have to make more food available. What do we do?"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 30-1.)

2. What should we do?

"In the early 1970s, nutritionists and research-minded physicians would discuss the observations of high levels of obesity in these poor populations, and they would occasionally do so with an open mind as to the cause. (*snip*)

Here's Rolf Richards, the British-turned-Jamaican diabetes specialist, discussing the evidence and the quandary of obesity and poverty in 1974, and doing so without any preconceptions: "It is difficult to explain the high frequency of obesity seen in a relatively impecunious [very poor] society such as exists in the West Indies, when compared to the standard of living enjoyed in the more developed countries.

Malnutrition and subnutrition are common disorders in the first two years of life in these areas, and account for almost 25 per cent of all admissions to pediatric wards in Jamaica. Subnutrition continues in early childhood to the early teens. Obesity begins to manifest itself in the female population from the 25th year of life and reaches enormous proportions from 30 onwards.'

When Richards says 'subnutrition,' he means there wasn't enough food. From birth through the early teens, West Indian children were exceptionally thin, and their growth was stunted. They needed more food, not just more nutritious food. Then obesity manifested itself, particularly among women, and exploded in these individuals as they reached maturity.

This is the combination we saw among the Sioux in 1928 and later in Chile— malnutrition and/or undernutrition or subnutrition coexisting in the same population with obesity, often even in the same families. (*snip*)

Referring to obesity as a 'form of malnutrition' comes with no moral judgments attached, no belief system, no veiled insinuations of gluttony and sloth. It merely says that something is wrong with the food supply and it might behoove us to find out what.(*snip*)

Again, the coexistence of underweight and overweight in the same populations and even in the same families doesn't pose a challenge to public-health programs; it poses a challenge to our beliefs about the cause of obesity and overweight."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 29-32.)

3. Being underweight and being overweight can coexist: My thoughts

<About undernutrition and overweight>

First, I would like to explain, based on my experience, that the coexistence of undernutrition and obesity are not contradictory messages.

I repeat that when I was very thin, under forty kilograms, at first, I was eating high-calorie foods such as deep-fried foods or sweet, but I couldn’t gain weight. And then, I realized that I could gain weight by digesting all the foods in my whole intestines and inducing intestinal starvation.

The easiest way to induce intestinal starvation was to eat digestible refined carbohydrates (rice, white bread, noodles, starches, etc.) and a little easy-to-digest protein (and not to eat other foods), but since it lacked energy and essential nutrients for my body, I felt dizzy from the undernutrition.

If I ate eggs, vegetables, beans, or fish, or drank milk to add more essential nutrients, though the nutritional profile was better, I couldn’t gain any weight. For me, it was because I couldn’t digest them well.

IIn short, a higher ratio of digestible refined carbohydrates in the meals and eating fewer fibrous vegetables, fat, and other indigestible foods are more likely to induce intestinal starvation and cause one’s set-point weight to increase.

It’s probably certain that a deficiency of vitamins and/or minerals can cause illnesses, but being overweight is not contradicting being in a state of undernutrition.

<About the coexistence of being underweight and overweight>

Getting back to what Caballero refered to, even if people eat similar foods in the same group, it may lead to a different result in the body.

Some people who digested all the foods in their whole intestines may have gained weight—which means their set-point weight went up by intestinal starvation— and ended up becoming overweight.

However, those who were not able to digest all the foods in their whole intestines remained underweight. I believe that leaving Just a little bit of undigested food in the intestines makes it hard to induce intestinal starvation. (Being extremely thin can cause poor digestion, so it makes it even harder for them to induce intestinal starvation.) A small difference sometimes makes a big difference in the end result.

To sum up, what happened in the groups in poverty situations is a similar phenomenon that is happening in our modern society.

When someone doesn't eat much and is fat, we tend to assume that they are inactive or have a slow metabolism. And when someone who eats a lot but is thin, we tend to assume that they are active or have a fast metabolism.

Most researchers just try to fit everything into the theory that “fat people eat too much or are physically inactive” for some reason.

However, if we look at these ideas I’ve presented with an open mind, we can say that this is the same phenomenon as the "coexistence of thin and obese" in the same population.

At the risk of repeating myself, being overweight is not necessarily the consequence of overeating.

2019.01.04

The Dilution Effect/ Pushing Out Effect of Carbohydrates: Does This Cause People To Gain Weight?

Contents

- If there were no carbohydrates

- Meals high in indigestible foods are not fattening

- The effect of carbohydrates that make it easier to gain weight

(1) Dilution effect

(2) Pushing out effet

<The bottom line>

When we consider that “eating a lot leads to gaining weight,” I believe you have the image of carbohydrates like bread, rice, and noodles in mind.

This time, I am going to explain the reason why carbohydrates (*1) make it easier for people to gain weight, not because of an increase in calories or of its tendency to raise blood sugar levels, but by other indirect ways.

(*1) Although technically sugar is also a sort of carbohydrate, I use the word carbohydrate here to mean “polysaccharide” such as starches, bread, and rice.

1. If there were no carbohydrates

When my total body weight fell to under forty kilograms, it would have been impossible to have gained weight without the help of carbohydrates. In my case, neither fat nor sugar could have done that … In other words, I would never have gained weight by eating cream-filled cakes or oily pork cutlets and fatty Chinese food. Next, I am going to explain the reason why.

First, not all carbohydrates are the same. Carbohydrates are mainly categorized by their chemical structure into monosaccharides, disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides.

However, substances like cellulose (a polysaccharide), which is treated as dietary fiber, non-digestible oligosaccharides and resistant starch, should be consumed to improve health.

Additionally, while simple carbohydrates like sugar may lead to temporary weight gain or blood sugar-related disorders, I believe they are not a cause of weight gain in the sense that they increase one’s set-point weight.

In terms of increasing the body's set-point weight, I believe the cause of weight gain is the consumption of easily digestible carbohydrates that are high in starch (polysaccharides) and low in dietary fiber, such as refined grains like rice and wheat, and potatoes.

Therefore, foods like brown rice, wholegrain bread, fried rice, and cold rice, while being the same type of carbohydrate, may produce different results.

These are known as low G.I. foods, which don't raise blood sugar levels easily, or resistant starches. In other words, these foods contain many indigestible components or take longer to digest and absorb.

2. Meals high in indigestible foods are not fattening

When you constantly consume foods that are less digestible or slowly digested and absorbed-such as the above-mentioned carbohydrates that don’t raise the blood sugar level, tough meats, fat, fibrous vegetables, seaweed, and dairy product-intestinal starvation is less likely to occur and you are less likely to gain weight, which means the set-point for body weight is unlikely to go up.

I’m simply saying that it is hard to gain weight if a lean person eats them properly every day.

Although a person who is already overweight may not lose weight by eating some less digestible foods, I consider that it may be possible to lose weight depending on how you eat them, since these foods are always discussed in dieting techniques.

3. The effect of carbohydrates that make it easier for people to gain weight

On the contrary, digestible refined carbohydrates that are high in starch (rice, rice porridge, white bread, potatoes, etc.) and processed starches extracted from plants promote overall digestion. By eating them together with digestible proteins, they make it easier to induce intestinal starvation.

Those are two effects that I can think of so far.

(1) Dilution effect

If you proportionally increase digestible carbohydrates (rice, noodles, bread, etc.) in the meal, the percentage of side dishes such as fat, meat, fish, and vegetables will be relatively smaller. The density of a spoonful of oil will be lower if you eat more bread or rice portions with soup (water).

When you eat some meat together with a slice of bread and soup, the density of the meat will be lower.

In other words, easily digestible carbohydrates and water are added and mixed in the stomach, and then the diluted nutrients are sent to the intestines. So, it will be easier to get hungry and induce intestinal starvation.

For example, let’s say you eat a hamburger and a potato, plus another piece of bread and tea. If we mix all of these in a blender, it will be something like meat diluted with starch and water.

In contrast, if we remove the bread and add mixed beans-mayonnaise salad… the dilution effect of carbohydrates will be less, and fiber and fat will be added.

On a caloric basis, mixed beans-mayonnaise salad is, e.g. 100kcal. However, adding it to the meal doesn’t have the same meaning as adding another piece of bread. This is why calorie intake basis thinking may go wrong.

Moreover, as seen in low-carb diets, what would happen if you decrease the intake of carbohydrates in the meal and instead increase proteins such as meat and fish, fat, and vegetables, etc.?

In this case, the opposite effect of the dilution effect occurs: dense nutrients are delivered to the intestines, which slows digestion and undigested food always remains in the gastrointestinal tract.

(2) Pushing out effect

"Balloon effect"

Starch-rich carbohydrates, when consumed with water, cause stomach bloating (I’ll call this the “balloon effect” of the stomach). And, if we eat carbs together with digestible side dishes such as stew (onion, potatoes, low-fat chicken, etc.), its holding time in the gut will be shorter since it’s easy to digest, and the food will be pushed out of the stomach fairly soon. Also, our intestines start to move actively and smoothly.

I had the problem with my stomach and intestines and often suffered from constipation or diarrhea.

But, when I ate Japanese soba noodles(*2) and small rice bowl dishes (chicken and egg over rice), it promoted regular bowel movements and relieved my symptoms several times.

(*2) If you don't know much about soba, it may be easier to imagine ramen noodles without oil.

On the other hand, you may think that eating fatty foods or deep-fried foods give us stamina. It actually means that those foods fill us up better than carbs do, and its energy could be sustained during sports such as a marathon or a soccer match.

That is to say, undigested foods stay longer in our stomach and intestines, so it’s more difficult to induce intestinal starvation.

The bottom line

(1) Simply put, incorporating fibrous foods and slow-digesting foods in your diet makes you less likely to gain weight compared to other meals with the same caloric content.

On the other hand, combining easily digestible foods (such as refined carbohydrates, proteins, and ultra-processed foods) in your diet makes you more likely to gain weight.

(2) Carbohydrates are generally classified into monosaccharides, disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides, depending on their chemical structure.

Substances like cellulose (polysaccharides) which are considered dietary fiber, non-digestible oligosaccharides, and resistant starch, would not cause weight gain and should be consumed to promote health.

I also believe that simple carbohydrates like sugar may cause an increace in blood sugar levels and temporary weight gain, but they are not a cause of weight gain in the sense that they increase one’s set-point weight.

(3) In terms of increasing the body's set-point weight, I believe the foods that may cause obesity are easily digestible carbohydrates (polysaccharides) high in starch, such as white rice, white bread, noodles, and potatoes.

These foods expand with water in the stomach (balloon effect) and may have a "dilution effect" or "push-out effect" in the digestive process, which might lead to intestinal starvation.

(4) Obesity among poverty-stricken people worldwide can be understood as the influence of cheap refined carbohydrates and unbalanced diets (lack of vegetables, etc.). Considering them, it may be easier to imagine that they are not gaining weight due to taking too many calories or sugar, but rather from consuming cheap carbohydrates as mentioned above.

[Related article] Wealthy People Get Fat? Poor People Get Fat?

2018.10.21

Do Carbohydrates Make Us Fat or Do Too Many Calories?: The Debate Since the 1800's

Contents

- Low carbohydrates go way back

- The reason why doctors couldn’t accept carbohydrate restriction

- Carbohydrates and fat have opposite properties. My thoughts

<The bottom line >

First, as many of you know, even carbohydrates contain four kcal of energy per gram. So, some readers may think, "After all, isn't being overweight ultimately caused by too many calories?"

But if you think, "too many calories are the cause," you should try to reduce the total amount of calories in your overall diet, mostly focusing on fat/oil intake, which has nine kcal per gram.

On the other hand, the argument that “too many carbohydrates cause weight gain” allows you to eat any amount of meat and fatty/oily foods as long as you cut back on carbs.

In this article, I will look back on the historical argument of whether carbohydrates or calories are the cause of weight gain, and at the end of this article, I would like to share my thoughts.

1.Low carbohydrates go way back

In Japan, a low-carb diet was trendy around 2015, but when we look around the world, this way was repeatedly conducted since the 1800’s. Please note that there are many quoted parts. I needed to share this information with you to explain my theory.

"Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin was born in 1755. (*snip*) His passion, though, was always food and drink, or what he called the “pleasures of the table.” He began writing down his thoughts on the subject in the 1790s; Brillat-Savarin published them in a book, The Physiology of Taste, in December 1825. (*snip*)

“Tell me what you eat,” Brillat-Savarin memorably wrote, “and I shall tell you what you are." (*snip*)

Over the course of thirty years, he wrote, he had held more than five hundred conversations with dinner companions who were “threatened or afflicted with obesity,” one “fat man” after another, declaring their devotion to bread, rice, pasta, and potatoes. This led Brillat-Savarin to conclude that the roots of obesity were obvious.

The first was a natural predisposition to fatten. “Some people,” he wrote, “in whom the digestive forces manufacture, all things being equal, a greater supply of fat are, as it were, destined to be obese.”

The second was “the starches and flours which man uses as the base of his daily nourishment,” and he added that “starch produces this effect more quickly and surely when it is used with sugar."

This , of course, made the cure obvious as well, ...(*snip*) (Brillat-Savarin wrote) ...”It can be deduced, as an exact consequence, that a more or less rigid abstinence from everything that is starchy or floury will lead to the lessening of weight.” (*snip*)

What Brillat-Savarin wrote in 1825 has been repeated and reinvented numerous times since. Up through the 1960s, it was the conventional wisdom, what our parents or our grandparents instinctively believed to be true."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 148-149.)

(*snip*)

"By the time, a French physician and retired military surgeon named Jean-Francois Dancel had come to the same conclusions as his countryman Brillat-Savarin. Dancel presented his thoughts on obesity in 1844 to the French Academy of Sciences and then published a book, Obesity, or Excessive Corpulence: The Various Causes and the Rational Means of a Cure.

Dancel claimed that he could cure obesity “without a single exception” if he could induce his patients to live “chiefly upon meat," and partake “only of a small quantity of other food."

Dancel argued that physicians of his era believed obesity to be incurable because the diets they prescribed to cure it were precisely those that happened to cause it. (*snip*)

“All food which is not flesh ―all food rich in carbon and hydrogen [i.e., carbohydrates] ―must have a tendency to produce fat,” wrote Dancel. (*snip*)

Dancel also noted that carnivorous animals are never fat, whereas herbivores, living exclusively on plants, often are."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 151-2.)

"Until the early years of the twentieth century, physicians typically considered obesity a disease, and a virtually incurable one, against which, as with cancer, it was reasonable to try anything. Inducing patients to eat less and/or exercise more was just one of many treatments that might be considered. (*snip*)

<1950's>

The effects of a carbohydrate-restricted diets were then confirmed in the 1950s by Margaret Ohlson, head of the nutrition department at Michigan State University, and by her student Charlotte Young.

When overweight students were put on conventional semi-starvation diets, Ohlson reported, they lost little weight and “reported a lack of ‘pep’ throughout... [and] they were discouraged because they were always conscious of being hungry.”

When they ate only a few hundred carbohydrate calories a day but plenty of protein and fat, they lost an average of three pounds per week and “reported a feeling of well-being and satisfaction. Hunger between meals was not a problem.”

The reports continued into the 1970s. (*snip*)

The diets were prescribed for obese adults and children, for men and women, and the result were invariably the same. The dieters lost weight with little effort and felt little or no hunger while doing so."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 151, 157-8.)

2.The reason why doctors couldn’t accept carbohydrate restriction

As you can see, by cutting back on carbohydrates and eating more of other foods such as meat and greasy food, the problem of being overweight seems to be solved...but this is where the "calorie principle" comes into play.

"By the 1960s, obesity had come to be perceived as an eating disorder. (*snip*)

Adiposity 101 was discussed in the physiology, endocrinology, and biochemistry journals, but rarely crossed over into the medical journals or the literature on obesity itself.

When it did, as in a lengthy article in The Journal of the American Medical Association in 1963, it was ignored. Few doctors were willing to accept a cure for obesity predicated on the notion that fat people can eat large portions of any food, let alone as much as they want. This simply ran contrary to what had now come to be accepted as the obvious reason why fat people get fat to begin with, that they eat too much.

But there was another problem as well. Health officials had come to believe that dietary fat causes heart disease, and that carbohydrates are what these authorities would come to call “heart-healthy."(*snip*)

After all, if dietary fat causes heart attacks, then a diet that replaces carbohydrates with more fatty foods threatens to kill us, even if it slims us down in the process. As a result, doctors and nutritionists started attacking carbohydrate-restricted diets."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 159-60.)

(*snip*)(In 1965)

"The Times article, 'New Diet Decried by Nutritionists: Dangers Are Seen in Low Carbohydrate Intake,' quoted Harvard's Jean Mayer as claiming that to prescribe carbohydrate-restricted diets to the public was 'the equivalent of mass murder.' (*snip*)

Well, first, as the Times explained, 'It is a medical fact that no dieter can lose weight unless he cuts down on excess calories, either by taking in fewer of them, or by burning them up.' We now know that this is not a medical fact, but the nutritionists didn't in 1965, and most of them still don't.

Second, because these diets restrict carbohydrates, they compensate by allowing more fat. It's the high-fat nature of the diets, the Times explained, that prompted Mayer to make the mass murder accusation."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page 161.)

3. Carbohydrates and fat have opposite properties. My thoughts

I ‘d like to talk about this controversy.

Several studies have shown that how we combine the three macronutrients (protein, fat, and carbohydrates) in the diet produces different results in body fat accumulation. It is thought that even the same one calorie has different energy used for digestion and absorption, different hormones to stimulate, and different pathways of how the calorie is metabolized in the body.

Of course I think these studies are great, but the point I'd like to add based on my theory is that "carbohydrates and fat are close to having opposite properties in their digestive processes."

First, refined carbohydrates are more easily digested than meats and fats, and the "dilution effect" or "push-out effect" they have makes our digestion go even faster and makes us feel hungrier.

If we eat an unbalanced diet that lacks vegetables, fat, and dairy products,etc., we are ultimately more prone to inducing intestinal starvation.

In contrast, fats and meats are less digestible. The time required for digestion depends on the quantity and type of food consumed, how we prepare food, or individual differences in digestive ability, but it is generally estimated to be 3-4 hours for proteins and 6-8 hours for fats.

In particular, when fat enters the duodenum, cholecystokinin, a hormone that promotes fat digestion and absorption, is secreted.

However, it is said that these hormones also inhibit the function of the stomach and slow down the gastric emptying process, which can cause stomach upset or bloating.

Plus, a diet low in carbohydrates and high in protein and fat sends dense nutrients to the digestive system, which slows overall digestion. As a result, I believe that it suppresses hunger and in turn, causes the absorption rate to decrease.

That is to say, depending on how we structure our diets, there may be a weight-loss effect even with increased caloric intake (for those who can digest protein and fat quickly, the weight-loss effect may be less pronounced) .

The bottom line

(1) From the early 1800’s through the 1960’s, several studies had shown that overweight people could lose weight without difficulty by replacing some carbohydrates in their diet with a lot of meat and fat. By that time, however, obesity was understood as an eating disorder, and this diet method was discussed only in physiology, endocrinology, etc.

(2) From the 1960’s to the late 1970’s, few physicians accepted the idea that fat people could lose weight by eating lots of meat and fat, because it obviously violated the "calorie principle.”

(3) In addition, health experts came to believe that fat in the diet caused heart disease and that carbohydrates were "heart-healthy." As a result, doctors and nutritionists began attacking low-carb diets.

(4) My thoughts: Both sides have a point, but the caloric intake does not determine everything. Different combinations of foods, even with the same calories, have different effects on weight management. In particular, carbohydrates and fat are close to having opposite properties in their digestive processes.

2017.12.10

Wealthy People Get Fat? Poor People Get Fat?

-

Contents

-

- Wealth is said to be the cause of obesity....

- The case of poverty and obesity

- Why were they fat?

- Though we have become wealthy, how is the quality of our food? My thoughts

I would like to share with you an interesting story based on profound research that is also relevant to my theory. I will conclude this post with my thoughts.

【Related article】The Combination of Thin and Overweight in the Same Poor Group Is Not Contradictory

1. Some believe that wealth is said to be the cause of obesity...

"Ever since researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) broke the news in the mid-1990s that the epidemic was upon us, authorities have blamed it on overeating and sedentary behavior and blamed those two factors on the relative wealth of modern societies.

■'Improved prosperity' caused the epidemic, aided and abetted by the food and entertainment industries, as the New York University nutritionist Marion Nestle explained in the journal Science in 2003.

'They turn people with expendable income into consumers of aggressively marketed foods that are high in energy but low in nutritional value, and of cars, television sets, and computers that promote sedentary behavior. Gaining weight is good for business.'

■The Yale University psychologist Kelly Brownell coined the term 'toxic environment' to describe the same notion.

Just as the residents of Love Canal or Chernobyl lived in toxic environments that encouraged cancer growth, the rest of us, Brownell says, live in a toxic environment 'that encourages overeating and physical inactivity.'

'Cheeseburgers and French fries, drive-in windows and supersizes, soft drinks and candy, potato chips and cheese curls, once unusual, are as much our background as tree, grass, and clouds. Computers, video games, and televisions keep children inside and inactive,' he says.(*snip*)

▽The World Health Organization (WHO) uses the identical logic to explain the obesity epidemic worldwide, blaming it on rising incomes, urbanization, 'shifts toward less physically demanding work...moves toward less physical activity...and more passive leisure pursuits.'

Obesity researchers now use a quasi-scientific term to describe exactly this condition: they refer to the 'obesigenic' environment in which we now live, meaning an environment that is prone to turning lean people into fat ones."

(Gary Taubes. Why We Get Fat. New York: Anchor Books, 2011, Pages 17-8.)

In Japan as well, this idea is widely accepted, and most experts on television explain that overeating and physical inactivity are the causes of obesity.

2. The case of poverty and obesity

However, what we have to consider here is that obesity is spreading in the poor layers of society, too.

"One piece of evidence that needs to be considered in this context, however, is the well-documented fact that being fat is associated with poverty, not prosperity-certainly in women, and often in men. The poorer we are, the fatter we're likely to be. (*snip*)

In the early 1970s, nutritionists and research-minded physicians would discuss the observations of high levels of obesity in these poor populations, and they would occasionally do so with an open mind as to the cause.(*snip*)

This was a time when obesity was still considered a problem of 'malnutrition' rather than 'overnutrition,' as it is today."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 18, 29.)

"Between 1901 and 1905, two anthropologists independently studied the Pima (Native American tribe in Arizona), and both commented on how fat they were, particularly the women.

Through the 1850s, the Pima had been extraordinarily successful hunters and farmers. By the 1870s, the Pima, however, were living through what they called the 'years of famine.' (*snip*)

When two anthropologists (Russell and Hrdlička) appeared, in the first years of the twentieth century, the tribe was still raising what crops it could but was now relying on government rations for day-to-day sustenance.

What makes this observation so remarkable is that the Pima, at the time, had just gone from being among the most affluent Native American tribes to among the poorest.

Whatever made the Pima fat, prosperity and rising incomes had nothing to do with it; rather, the opposite seemed to be the case. (*snip*)

(A quarter-century after Russell and Hrdlička visited Pima)

Two researchers from the University of Chicago studied another Native American tribe, the Sioux living on the South Dakota Crow Creek Reservation.

These Sioux lived in shacks 'unfit for occupancy,' often four to eight family members per room. Many had no plumbing and no running water. Forty percent of the children lived in homes without any kind of toilets. Fifteen families, with thirty-two children among them, lived "chiefly on bread and coffee.' This was poverty almost beyond our imagination today.

Yet their obesity rates were not much different from what we have today in the midst of our epidemic : 40 percent of the adult women on the reservation, more than a quarter of the men, and 10 percent of the children, according to the University of Chicago report, 'would be termed distinctly fat.'"

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Pages 20-24.)

1950-1980’s

This combination of obesity and undernutrition existing in the same populations have been found and reported from around the world, including the West Indies, South Africa, Chile, Ghana, and Jamaica.

3. Why were they fat?

<About the case of Manhattanites, in the early 1960's>

"This was first reported in a survey of New Yorkers-midtown Manhattanites-in the early 1960s: obese women were six times more likely to be poor than rich; obese men, twice as likely. (*snip*)

Can it be possible that the obesity epidemic is caused by prosperity, so the richer we get, the fatter we get, and that obesity associates with poverty, so the poorer we are, the more likely we are to be fat?

It's not impossible. Maybe poor people don't have the peer pressure that rich people do to remain thin. Believe it or not, this has been one of the accepted explanations for this apparent paradox.

Another commonly accepted explanation for the association between obesity and poverty is that fatter women marry down in social class and so collect at the bottom rungs of the ladder; thinner women marry up.

A third is that poor people don't have the leisure time to exercise that rich people do; they don't have the money to join health clubs, and they live in neighborhoods without parks and sidewalks, so their kids don't have the opportunities to exercise and walk.

These explanations may be true, but they stretch the imagination, and the contradiction gets still more glaring the deeper we delve."

(Taubes. Why We Get Fat. Page18-19)

<About the case of the Pima (Native American tribe in Arizona >

"So why were they fat? Years of starvation are supposed to take weight off, not put it on or leave it on, as the case may be. And if the government rations were simply excessive, making the famines a thing of the past, then why would the Pima get fat on the abundant rations and not on the abundant food they'd had prior to the famines?

Hrdlička also thought that their physical inactivity was the cause of obesity because they were sedentary in comparison with what they used to be. This is what Hrdlička called 'the change from their past active life to the present state of not a little indolence.' But then he couldn't explain why the women were typically the fat ones, even though the women did virtually all the hard labor in the villages—harvesting the crops, grinding the grain, even carrying the heavy burdens.

▽Perhaps the answer lies in the type of food being consumed, a question of quality rather than quantity.

This is what Russell was suggesting when he wrote that 'certain articles of their food appear to be markedly flesh producing.'