Topics

03/03/2025

The Rise in Obesity is Closely Linked to the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods

Summary

(1) The NOVA classification system, developed in 2009 by a research group at the University of São Paulo, categorizes foods into four groups based on the degree and purpose of processing rather than type or their nutritional content.

【1】Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

【2】Processed culinary ingredients

【3】Processed foods (PFs)

【4】Ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are formulations made from multiple ingredients and undergo numerous industrial processes. They include sweet or savory snacks, confectioneries, instant foods, processed meat products such as sausages and ham, and most fast foods.

Increased UPF consumption is believed to be linked to rising rates of obesity and diet-related diseases.

(2) UPFs are high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, salt, saturated fats, and trans fats, making them energy-dense. On the other hand, they are poor sources of fiber, protein, and micronutrients.

Additionally, they often contain flavorings, colorings, emulsifiers, preservatives, and other cosmetic additives.

(3) Since the 1980’s, UPF consumption has surged not only in developed countries but also in developing nations. UPFs now account for more than 50% of total daily energy intake on average in the U.S., U.K., and Canada.

(4) Several studies examining the relationship between UPF consumption and obesity have clearly shown that higher UPF intake is associated with an increased risk of obesity. In contrast, greater consumption of natural foods, such as vegetables, has been found to be inversely correlated with obesity.

(5) A U.S. research group found that individuals with high UPF consumption tend to eat fewer natural foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and fish, leading to a significant decline in overall diet quality.

(6) Processed food diets may result in lower diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) compared to whole-food diets, potentially increasing net energy intake. Additionally, UPF diets may lead to overeating because they provide less satiety and make individuals feel hungrier than unprocessed food diets.

<My thought>

(7) Generally, UPFs are considered to promote obesity when consumed in excess due to their high energy density. However, I want to highlight the risk of “ultra-processing” itself. Since UPFs are low in nutrients and fiber, and are easily digested, if a diet is skewed toward refined carbohydrates and UPFs while lacking natural foods like vegetables, it can lead to intestinal starvation, potentially raising the body's set-point weight.

(8) It is not an overstatement to say that the sharp rise in being overweight, obesity, and many lifestyle-related diseases coincided with the rapid industrialization of food processing in the 1970’s and 80’s.

(9) The World Obesity Federation (WOF) warns that without policy changes and effective obesity prevention measures, more than half of the global population will be classified as obese or overweight by 2035. In my opinion, instead of focusing solely on “calories,” policies need to emphasize factors such as the degree of food processing, the number of chews, and the digestibility of food.

【 Full text 】

-

Contents

-

- Food classification by NOVA

- The Issues with Ultra-Processed Foods

- Consumption of UPFs and its association with obesity

- Impact of UPFs on overall diet

(1) Decrease in overall diet quality

(2) Increase in net energy intake

(3)Effects on ad libitum energy intake - Why do UPFs cause weight gain?

- Desired future measures

The endless diet wars among factions in various diets—such as low-carb, ketogenic, paleo, low-fat, and vegan—have caused substantial public confusion and fostered mistrust in nutritional science. However, it is not widely known that diverse diets recommendations often share a common piece of advice: to avoid ultra-processed foods[1].

Empirical evidence has shown that the rising obesity rates closely parallel the increased consumption of ultra-processed foods in many countries.

In this discussion, I’d like to explore the reasons behind this and, finally, mention how it relates to my intestinal starvation theory.

1. Food classification by NOVA

NOVA (not a acronym) is the food classification that categorizes foods based on the degree and purpose of food processing, rather than their nutritional content. It was developed in 2009 by a research group at the University of São Paulo in Brazil[2].

Conventional food classification systems categorize foods and ingredients based on their botanical origin or animal species, and nutrient composition.

As a result, whole grains are often grouped with breakfast cereals or cookies, and fresh chicken or pork are often classified alongside chicken nuggets or sausages.

When considering their their impact on health and disease, conventional food classifications no longer worked well[3].

NOVA classifies foods into four groups based on the nature, extent, and purpose of the industrial processing they undergo.

(1)Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

Fresh fruits and vegetables, and other natural foods (such as grains, milk, fish, and meat) that have undergone processes like removing inedible parts, drying, grinding, pasteurization, chilling, freezing, or vacuum-packaging.

(2)Processed culinary ingredients

Substances derived from Group 1 foods or from nature through processes that include pressing, refining, milling, or drying, such as oils, butter, sugar, and salt. These processed culinary ingredients are typically not consumed on their own.

(3)Processed foods (PFs)

These are typically made by adding Group 2 substances to Group 1 foods. Examples include canned vegetables, fruit in syrup, canned fish, cheese, and freshly made breads.

(4)Ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

These are formulations created by combining many ingredients and undergoing a sequence of industrial processes. Examples include breakfast cereals, soft drinks and fruit juices, sweet or savory snacks, confectioneries, instant foods, reconstituted meat products such as sausages and nuggets, and most fast food items[3,4].

2. The issues with ultra-processed foods

Food processing, in essence, refers to “various operations by which raw foodstuffs are made suitable for consumption, cooking, or storage,” and virtually all foods undergo some form of processing before being eaten. Therefore, processing itself is not inherently bad.

However, ultra-processed foods are not modified foods but formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives through multiple industrial processes, with little to no Group 1 natural foods[3].

These foods are high in refined grains, added sugars, salt, saturated fats, and trans fats, making them energy-dense. On the other hand, they are poor sources of dietary fiber, protein, and micronutrients.

Additionally, flavorings, colorings, emulsifiers, non-sugar sweeteners, and other cosmetic additives are often added to these products to mask undesirable qualities of the final product[5].

Nevertheless, since the 1980s, the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has rapidly increased not only in developed countries but also in developing nations, largely driven by transnational corporations.

UPFs are highly appealing because they are hyper-palatable and addictive, inexpensive, have a long shelf life, and can be consumed anytime, anywhere[3].

The evidence based on the NOVA classification so far suggests that the decline in minimally processed foods and home cooking, alongside the replacement of food supplies with ultra-processed foods, is associated with unhealthy nutritional profiles and an increase in several diet-related diseases[3].

3. Consumption of UPFs and its association with obesity

In studies on adults reporting the proportion of total daily energy intake from UPFs, the highest levels (on average) were reported in the USA (55.1–56.1%), followed by the UK (53–54.3%), Canada (45.1–51.9%), France (29.9–35.9%), Brazil (20–29.6%), Spain (24.4%), and Malaysia (23%)[6].

A cross-sectional study (2005–2014) on American adults, who were found to consume an average of 56.1% of their total energy intake from UPFs, revealed significant differences across quintiles. Those in the highest quintile (Note 1) consumed 84.5% of their total energy intake from UPFs, while those in the lowest quintile accounted for 25.4%[7].

(Note 1: Quintile refers to one of five equal measurements that a set of things can be divided into)

♦A cross-sectional time series study conducted in fifteen Latin American countries revealed that sales of UPFs were associated with changes in body weight in twelve of these countries from 2000 to 2009[8].

A cross-sectional study based on data from Brazil’s 2008–2009 Household Budget Survey found that household availability of UPFs was positively correlated with both the average BMI and obesity prevalence. Those in the highest quartile (Note 2) of household consumption of UPFs were 37% more likely to be obese compared to those in the lowest quartile[9].

(Note 2: Quartile refers to one of four equal measurements that a set of things can be divided into)

♦A study involving 6,143 participants from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008–2016) classified foods recorded in four-day food diary according to the NOVA system. Consumption of UPFs was associated with increases in BMI, waist circumference, and obesity rates in both men and women. For every 10% increase in UPF consumption, the obesity rate increased by 18%.

Higher consumption of UPFs was observed among men, white British individuals, smokers, younger people, and those in lower social class groups[10].

♦A cross-sectional study involving 19,363 adults aged 18 and older from the 2004 Canadian Community Health Survey, found that individuals in the highest quintile of UPF consumption were 32% more likely to be obese compared to those in the lowest quintile. Higher UPF intake was associated with being male, younger age, lower educational attainment, physical inactivity, smoking, and being born in Canada[4].

♦A prospective cohort study conducted since 1999 among graduates of the University of Navarra in Spain tracked 8,451 participants who were not overweight at baseline for about nine years. Those in the highest quartile of UPF consumption had a 26% higher risk of developing overweight or obesity compared to those in the lowest quartile.

Moreover, on average, they consumed more fast food, fried foods, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages, while, in contrast, their vegetable intake was the lowest. A higher consumption of UPFs was associated with lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet[11].

3. Impact of UPFs on overall diet

(1) Decrease in overall diet quality

♦A U.S. research group analyzed data on 5,919 children and 10,064 adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2015-2018) to investigate the relationship between UPF consumption and overall diet quality. Diet quality was assessed using the American Heart Association (AHA) diet score and Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2015 score.

The estimated proportion of children with a poor diet gradually increased from 31.3 % in the lowest quintile of UPF consumption to 71.6 % in the highest quintile. Similarly, among adults, this proportion rose from 18.1 % in the lowest quintile to 59.7 % in the highest quintile.

As UPF intake increased, the consumption of healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, and fish significantly decreased, while the intake of unhealthy foods such as refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, and added sugars increased.

The research group concluded that higher consumption of UPFs was associated with substantially lower diet quality among children and adults. These findings were consistent with previous studies conducted in several countries[12].

♦An Italian research group hypothesized that meal timing could also be linked to food processing and conducted a study to test this. They analyzed data on 8,688 individuals from the Italian Nutrition & Health Survey (INHES), conducted between 2010 and 2013. Subjects were classified as early or late eaters based on the population’s median timing for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Results showed that late eaters (breakfast after 7 AM, lunch after 1 PM, and dinner after 8 PM) were less likely to consume unprocessed or minimally processed foods compared to early eaters, while they consumed more processed foods (PFs) and UPFs. Late eating was also inversely associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet[13].

The Mediterranean diet, which primarily consists of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish, has been shown to be linked to reduced weight gain[14].

(2) Increase in net energy intake

A group of researchers in the U.S. conducted a crossover comparative study to ascertain the net energy intake of two different diets: one consisting of specific processed foods and the other of an isocaloric whole-food (WF) diet. Eighteen subjects consumed two types of sandwiches with the same calorie content but differing in processing levels.

The WF meal consisted of multigrain bread (containing whole sunflower seeds and whole-grain kernels) and cheddar cheese, while the PF meal consisted of white bread and a processed cheese product.

In this study, diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT)(Note 3) after consuming the PF meal was 46.8 % lower than that of the WF meal. The researchers concluded that this difference in DIT led to a 9.7 % increase in net energy-gain for the PF meal[15].

(Note 3) Diet induced thermogenesis (DIT) is the process by which the body increases its energy expenditure for several hours in response to food intake.

Regarding the significant reduction in diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) observed with the PF meal, the researchers provided the following analysis:

Compared to whole foods, PFs are characterized by lower nutrient density (a lower content and diversity of nutrients per calorie), less dietary fiber, and an excess of simple carbohydrates. As a result, PFs are structurally and chemically simpler than whole foods, making them easier to digest[15,16].

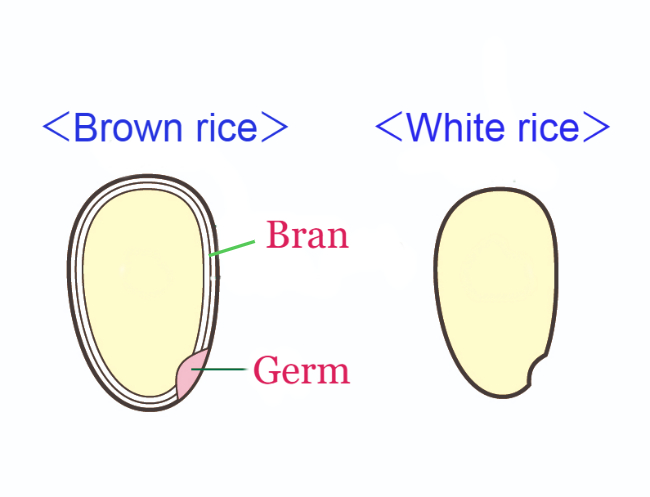

In grain refinement, most of the bran and germ are removed, resulting in the loss of nutrients (such as vitamins, minerals, and proteins), fiber, and phenols they provide.

Consequently, PFs tend to have fewer metabolites, leading to reduced enzyme production and peristalsis (Note 4), easier absorption, and less secondary metabolism—all of which contribute to lower DIT[15, 17].

Additionally, the loss of fiber reduces meal bulk and tends to slow satiety, both of which can lead to an increase in daily caloric intake[15, 18].

(Note 4:the repeated movements made by the muscle walls in the digestive tract tightening and then relaxing)

(3)Effects on ad libitum energy intake

A group of U.S. researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the effects of ultra-processed versus unprocessed diets on ad libitum energy intake in twenty adults with stable body weight. Subjects were randomly assigned to either the ultra-processed or calorie-matched unprocessed diet for two weeks, followed by the alternate diet for another two weeks.

In this experiment, participants were allowed to eat additional food after meals. As a result, they consumed more energy (459±105 kcal /day) during the ultra-processed diet and gained 0.4±0.1 kg of body fat. In contrast, they lost 0.3±0.1 kg of body fat during the unprocessed diet.

Fasting blood tests showed that levels of the appetite-suppressing hormone peptide YY (PYY) increased during the unprocessed diet as compared with both the ultra-processed diet and baseline. Also, levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin decreased during the unprocessed diet compared to baseline. This suggests that participants felt less hungry during the unprocessed diet, whereas the ultra-processed diet provided less satiety, making participants feel hungrier[19].

4. Why do UPFs cause weight gain?

I would like to explain the link between consumption of UPFs and an increase in obesity from the perspective of intestinal starvation.

Since the development of the NOVA classification, various studies have focused on the degree of food processing rather than calorie content, which is noteworthy.

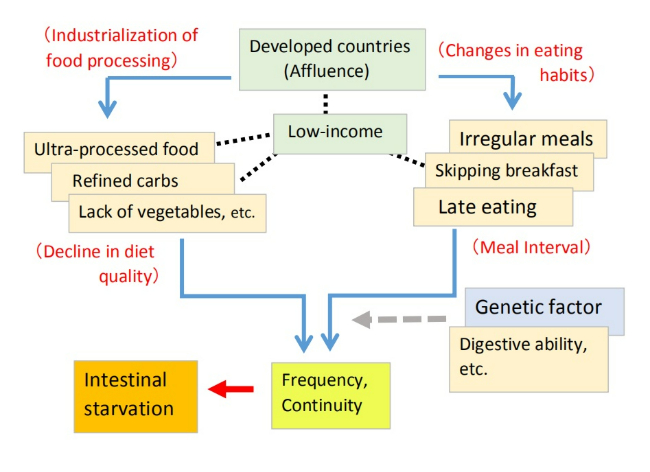

In the past, factors such as refined carbohydrates, fast food, late-night eating, lack of vegetables, wealth, and poverty have been discussed as causes of being overweight. However, how these factors interact had not been clearly proven.

This time, research has shown that increased UPF consumption itself is linked to an overall decline in diet quality, lack of vegetables, late-night eating, and lower-income groups in developed countries.

Through this blog, I have explained that a combination of factors—such as an unbalanced diet leaning toward refined carbohydrates and UPFs, a lack of vegetables, and an irregular lifestyle—can induce intestinal starvation, potentially raising the body's set-point weight.

UPFs are often high in energy density, so they are generally believed to promote obesity when overeaten. However, I believe the biggest issue is the "ultra-processing" itself, as these foods are digested and absorbed more quickly than natural foods.

If the diet is skewed toward refined carbohydrates and UPFs, and the overall diet quality declines, blood sugar levels can fluctuate sharply. Additionally, since these foods leave nothing behind in the intestines after digestion, intestinal starvation can be triggered (Note 5).

The fact that adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the consumption of natural foods like vegetables are inversely correlated with obesity supports my perspective.

In Japan, In my opinion, the consumption of UPFs such as instant foods, cookies, sweet bread, and chocolate confection is not necessarily low. However, one reason Japan’s obesity rate is lower than in Western countries may be its rice-based food culture, and the fact that many Japanese people still follow traditional eating habits.

(Note 5: Foods high in fat, such as ice cream, take longer to digest and may help prevent intestinal starvation.)

5. Desired future measures

The World Obesity Federation (WOF) warns that if policy directions remain unchanged and no effective measures are taken to prevent and treat obesity, more than half of the global population will be classified as overweight or obese by 2035.

I think this suggests that past policies focused solely on "calories in/ calories out" have not been particularly effective.

What we need now is a shift in focus from "calories" to factors such as the degree of food processing, the number of chews, and digestibility in policymaking.

With traditional dietary habits in many parts of the world, minimally processed natural foods were gradually digested in the digestive tract, allowing energy and nutrients to enter the bloodstream over several hours, while indigestible components like fiber helped maintain gut health.

Even if refined carbohydrates—such as white rice or bread—were included, the overall dietary quality likely remained high.

Even when people felt hungry, fiber and other undigested matter remained in the gut. As a result, there was little need to worry about caloric intake.

However, many people today prefer soft foods that require little chewing and have become overly reliant on refined carbohydrates and UPFs. These diets are low in nutrients and fiber, making them easy to digest, allowing the body to absorb large amounts of energy with minimal effort.

Moreover, once all the food is fully digested in the intestines, a signal that “there is no food” might be sent to the brain.

Such dietary habits were likely rare, if not nonexistent, in human history—at least until around 1970. It is not an overstatement to say that the sharp rise in being overweight, obesity, and many lifestyle-related diseases coincided with the rapid industrialization of food processing in the 1970’s and 80’s.

<References>

[1]Katz DL, Meller S. Can we say what diet is best for health? Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:83-103.

[2]Monteiro CA et al. NOVA. The star shines bright. Food classification. Public Health. World Nutr. J. 2016, 7, 28–38.

[3]Monteiro CA et al. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Jan;21(1):5-17.

[4]Nardocci M et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2019 Feb;110(1):4-14.

[5]Fiolet T et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018 Feb 14;360:k322.

[6]Elizabeth L et al. Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 30;12(7):1955.

[7]Juul F et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2018 Jul;120(1):90-100.

[8]Ultra-processed food and drink products in Latin America: trends, impact on obesity, policy implications. Pan American Health Organization, Washington (DC) (2013)

[9]Canella DS et al. Ultra-processed food products and obesity in Brazilian households (2008-2009). PLoS One. 2014 Mar 25;9(3):e92752.

[10]Rauber F et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and indicators of obesity in the United Kingdom population (2008-2016). PLoS One. 2020 May 1;15(5):e0232676.

[11]Mendonça RD et al. Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016 Nov;104(5):1433-1440.

[12]Liu J et al. Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods and Diet Quality Among U.S. Children and Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2022 Feb;62(2):252-264.

[13]Bonaccio M et al. Association between Late-Eating Pattern and Higher Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food among Italian Adults: Findings from the INHES Study. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 20;15(6):1497.

[14]Beunza JJ et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet, long-term weight change, and incident overweight or obesity: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Dec;92(6):1484-93.

[15]Barr SB, Wright JC. Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food Nutr Res. 2010 Jul 2;54.

[16]Fereidoon Shahidi. Nutraceuticals and functional foods: Whole versus processed foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology, Volume 20, Issue 9, 2009, Pages 376-387.

[17]Secor SM. Specific dynamic action: a review of the postprandial metabolic response. J Comp Physiol B. 2009 Jan;179(1):1-56.

[18]Roberts SB. High-glycemic index foods, hunger, and obesity: is there a connection? Nutr Rev. 2000 Jun;58(6):163-9.

[19]Hall KD et al. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab. 2019 Jul 2;30(1):67-77.e3.