Topics

06/20/2024

The Overfeeding Experiment Suggests That "Overeating" Is Not the Cause of Obesity

Contents

- Can overfeeding experiments make people obese?

- Subsequent overfeeding experiments

- Can metabolism explain this weight regain?

- Difference between obesity and overfeeding experiments: My thoughts

1. Can overfeeding experiments make people obese?

According to George A. Bray (as of 2020, an emeritus professor at Pennington Biomedical Research Center), until the 1960’s, obesity was viewed as a "lack of will power," and many people thought, and some said "if only these patients would push themselves away from the table, they would not have this problem."

With this view of obesity, he reflects that the turning point for obesity being accepted as a bona fide area of academic interest were the studies on overfeeding. Overfeeding studies began to provide valuable insights into the biology of obesity. For Doctor Bray, who was a postdoctoral fellow at the New England Medical Center Hospital in Boston at the time, the excitement that was generated when the Vermont overfeeding studies were first presented in 1968 was unforgettable[1].

This was the case with the overfeeding experiments conducted by Doctor Ethan Sims in the late 1960’s. Until then, it was commonly believed that, "overeating obviously leads to obesity," so few such experiments had been conducted.

According to Dr. Jason Fung, the author of “The Obesity Code,” Dr. Sims recruited lean students at the nearby University of Vermont and encouraged them to eat a lot to gain weight. However, despite what both he and the students had expected, the students did not become obese.

Suspecting that the students might have been increasing their exercise, Dr. Sims changed course. He then recruited convicts at the Vermont State Prison as subjects. Physical activity was strictly controlled, and attendants were present at every meal to ensure the calories-4000 per day-were eaten.

Although the prisoners’ weight initially rose, it then stabilized. While some prisoners gained more than twenty percent of their original body weight, the extent of weight gain varied significantly among them[2] .

Over two hundred days on this overfeeding regimen, twenty inmates gained an average of twenty to twenty-five pounds. (About 10 kg.) However, once the experiment ended and their caloric intake returned to normal, the men had difficulty maintaining the weight gain, and most shed all the weight they had gained relatively easily. The exceptions were two inmates who struggled to lose that weight[3].

At the time, Dr. Bray was allowed to participate as a co-researcher in Dr. Sims' experiment to examine the metabolic changes occurring in adipose tissue during the weight gain that followed overfeeding.

Later, in 1972, he conducted his own overeating experiment, using himself as a guinea pig. Initially, he tried to double what he usually ate at each meal, but he couldn't finish, so he switched to energy-dense foods, such as ice cream.

Over the next ten weeks, he gradually gained ten kilograms, and repeated his tests such as measuring the thermic effect of foods.

But once he stopped stuffing himself, his weight rapidly decreased, returning to his original seventy-five kilograms six weeks later, and he has maintained this weight with no trouble ever since.

Following his self-experiment, the other four volunteers in this study began overeating in the summer of 1972. When the experiment ended, all the volunteers returned to their baseline weight.

Dr.Bray states that this rapid return to normal weight contrasts with the difficulties people with spontaneous obesity have in losing weight, and the even more difficult task of a maintaining a lower weight. Many who develop obesity over years suffer from a different kind of pain than those of us who acutely gain weight by overfeeding. For them, the obesity “slips up” on them and once present, is difficult to reverse.

The history of overfeeding and underfeeding trials and other lines of evidence clearly show that obesity prevention and treatment cannot simply rely on the advice to "eat less and exercise more." [1]

2. Subsequent overfeeding experiments

Alex Leaf (Western States University) and Jose Antonio (Nova Southeastern University) reviewed overfeeding studies conducted up to 2017 that evaluated various combinations of macronutrient overfeeding and its effects on body composition.

They found twenty-five overfeeding studies that reported changes in fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM), in addition to changes in body weight. The study durations ranged from nine to one hundred days, and all but four were conducted in sedentary populations[4]. Notably, the objectives of each study varied, and not all mentioned weight loss following the end of the experiments.

To give a few examples, a study on identical twins was published in 1990.

■Bouchard (Laval University, Canada) et. al. recruited twelve pairs of young adult male identical twins (twenty-four individuals) with no exercise habits. Each participant's energy requirements were measured during a two-week base-line period, and after that, they were overfed by 1000 kcal per day (comprising 15% protein, 35% fat, and 50% carbohydrates), six days per week, for a total of eighty-four days during a one hundred-day period. The men were housed in a closed section of a university dormitory, and were under supervision by staff all day.

The mean weight gain was 8.1 kg, of which 67% was fat mass (FM). However, the weight gain varied widely among participants, ranging from 4.3 to 13.3 kg[5].

Four months after the experiment ended, the twins' average weight was 61.7 kg, which was only 1.3 kg higher than their baseline weight of 60.4 kg, indicating they had almost returned to their original weight[1].

■Conford (University of Michigan) et. al. conducted a study in 2012 involving nine healthy, non-obese adults (seven men and two women). The participants were admitted to the hospital for two weeks, during which time they ate 4000 kcals per day (comprising 15% protein, 35% fat, and 50% carbohydrates). Their energy requirements were determined during a one-week baseline period before the start of the experiment. In addition to three main meals, they had four snacks each day. The average weight gain was 2.1 kg, of which 67 % was fat mass (FM).[6]

The summary of this review indicates that overfeeding healthy, sedentary adults with a diet moderately high in both carbohydrates and fats (35-50% energy intake each) and low in protein (11-15%) primarily results in a gain in fat mass (FM), which accounts for 60-70 % of the weight gain. Additionally, the increase in fat-free mass (FFM) may be due to an increase in body water content rather than skeletal muscle tissue. In contrast, diets with significantly increased protein intake showed favorable changes in body composition, even with increased energy intake[4].

3. Can metabolism explain this weight regain?

Why did the participant’s weight rapidly return to normal over the ensuing weeks when they stopped overeating?

According to Dr. Bray, one of the striking findings in this Vermont study was that to maintain the weight they gained after overfeeding, they required more energy per unit surface area than before weight gain. When Dr. Bray moved to the University of California in 1970, his new lab began operating to explore his hypothesis about why extra energy was required to maintain the increased weight[1].

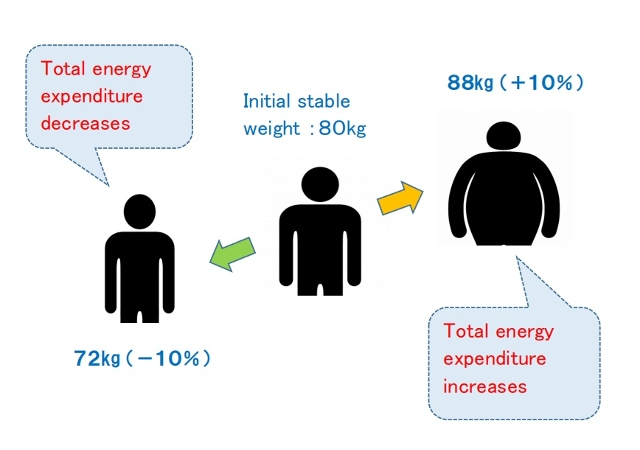

■Leibel (Rockefeller University) et. al. conducted a study in 1995 involving eighteen obese (BMI of 28 or higher) subjects (Group A) and twenty-three subjects who had never been obese (Group B).

They measured changes in energy expenditure under three conditions: at their usual body weight, after losing more than 10 percent of their body weight by underfeeding, and after gaining 10 percent of their body weight by overfeeding.

When maintaining a body weight at a level 10% or more below their initial weight, the total energy expenditure decreased by 8±5 kcal per kilogram per day in Group A and by 6±3 kcal in Group B.

Conversely, when maintaining a body weight at a level 10% above their initial weight, total energy expenditure increased by 8±4 kcal in Group A and by 9±7 kcal in Group B.

The study concluded that maintenance of a reduced weight or elevated body weight is associated with compensatory changes in energy expenditure, which resist maintaining the altered body weight and function to restore the original weight. This suggests that the long-term effectiveness of obesity treatment through caloric reduction may be limited[7].

4. Difference between obesity and overfeeding experiments: My thoughts

As Dr. Bray mentioned, I also believe that weight gain from temporary excessive caloric intake is due to body mechanisms entirely different from those underlying fundamental obesity. If compensatory metabolic mechanisms resist changes in body weight, why do some people continue to gain weight?

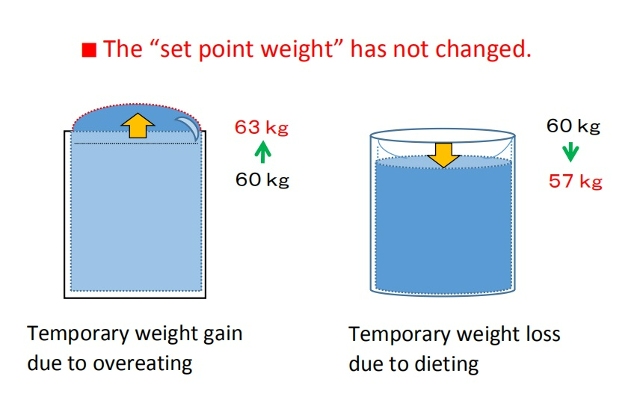

As I have repeatedly mentioned through this blog, the difference between people who are overweight and lean can be explained by the difference in set-point for body weight. (One's set-point weight goes up through intestinal starvation.)

For example, suppose a person who normally weighs a stable sixty kg is temporarily overfed and reaches sixty-three kg.

This can be compared to a glass of water that is usually filled to about 97% now being filled to 100%, and then surface tension causing the water to rise above the rim.

Conversely, maintaining a weight of fifty-six kg by eating less is like the water level temporarily decreasing, causing a dip in the surface of the water.

In both cases, the set-point weight has not changed.

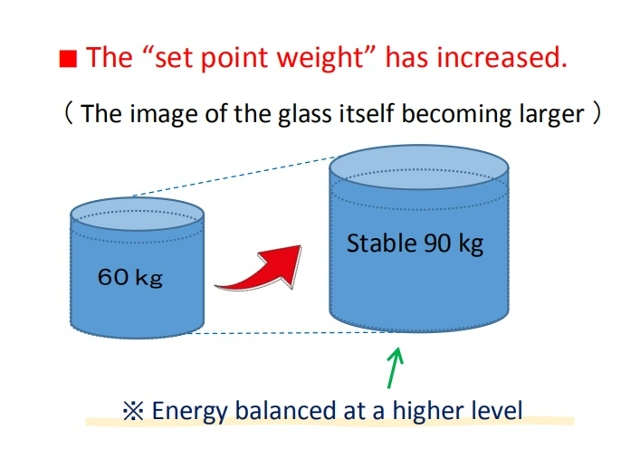

In contrast, if a person who originally weighs sixty kg gradually gains weight over several years, and then maintains a stable weight of ninety kg, this indicates that the set-point weight itself has increased, meaning the glass has grown larger, with energy balancing at a higher level.

Today, we are sometimes said to be living in an "obesogenic environment" that promotes obesity, but that does not necessarily mean consuming high-calorie foods or living sedentary lifestyles. As some researchers have already mentioned, calorie counting is clearly of little significance. Changes in caloric intake only lead to temporary weight gain or loss.

Rader, the "obesogenic environment" in my opinion is related to foods that are overly digestible foods (refined carbohydrates, fast food, processed foods, etc.) and an imbalanced diet (lack of vegetables, etc.). When these factors overlap with some other conditions such as skipping breakfast or eating late dinners, intestinal starvation is more likely to be induced.

Of course, researchers will say that in order to gain weight, more energy must be taken into the body than before. For more on why intestinal starvation leads to greater energy intake and weight gain, please refer to the article below.

[Related article] Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

<References>

[1]Bray GA. The pain of weight gain: self-experimentation with overfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020 Jan 1;111(1):17-20.

[2] Fung J, The Obesity Code, Greystone books, 2016, P114-116.

[3] Jou C. The biology and genetics of obesity--a century of inquiries. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 15;370(20):1874-7.

[4] Leaf A, Antonio J. The Effects of Overfeeding on Body Composition: The Role of Macronutrient Composition. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017 Dec 1;10(8):1275-1296.

[5] Bouchard C et al. The response to long-term overfeeding in identical twins. N Engl J Med. 1990 May 24;322(21):1477-82.

[6] Cornford AS et al. Rapid development of systemic insulin resistance with overeating is not accompanied by robust changes in skeletal muscle glucose and lipid metabolism. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013 May;38(5):512-9.

[7] Leibel RL et al. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995 Mar 9;332(10):621-8.