Topics

08/14/2019

Gaining Weight by Intestinal Starvation; What Does It Mean?

Contents

- Hunger in Africa and hunger in the modern era

- Why do we gain weight during periods of starvation?

- What happens when one’s set-point weight is elevated?

Let me explain something about the core of this blog.

Perhaps for most of you it is hard to believe me, but I’ll just write the facts as they are, as I experienced them. I did not write this from my imagination, but based it on my own analysis of what actually happened to me.

When I got into college, my total body weight fell down to the thirty-kilo range, so I knew exactly why I gained almost five kilos so rapidly in a few days, even though I didn’t eat much.

1. Hunger in Africa and hunger in the modern era

The idea of storing fat in the body as a reserve against starvation is something every researcher considers at one time or another.

However, it is said that this theory is an idea that has been rejected by researchers throughout history. This is because many overweight people often eat more, and many African refugees are thin and malnourished.

One might say, “If starvation makes us fat, then African refugees would be obese.”

However, please understand that this is a true state of starvation (malnutrition) in which the people can’t eat even if they want to, and I’m stating that it is different from what I call “intestinal starvation.”

African refugees do not have access to digestible food, and malnutrition even diminishes their ability to digest food and nutrients.

In contrast, many of us in developed countries are more likely to eat westernized foods made from wheat, meat, eggs, etc., which provide good nutrition and are easier to digest. Therefore, if we focus on the inner workings of our intestines, we are more prone to inducing intestinal starvation.

The reality is that being overweight has become a problem even among the poor populations in the world. What is common in these cases is not the excessive intake of calories or sugars, but rather a diet that is low in nutritional value and unbalanced, often due to a reliance on inexpensive refined carbohydrates and a lack of vegetables.

2. Why do we gain weight during periods of starvation?

In my blog, I mentioned that one’s set-point for body weight goes up by inducing intestinal starvation, and I want to explain what it means here. For the sake of explanation, I will use plants as an example.

(1) For plants, eating food and gaining weight is done by adding "fertilizer." This fertilizer is the equivalent to our diet, and of course, we need to use fertilizer periodically for growth.

However, using too much fertilizer doesn’t usually result in producing a bigger plant, and if we use it too often, it may sometimes have a negative effect.

The same goes for humans, and just eating a lot of calories doesn’t necessarily mean we all gain weight and become overweight. Even if we eat only one meal a day, as long as it’s well-balanced, there will be enough nutrition left in the intestines to be absorbed.

(2)Using an example of a plant, weight gain by inducing intestinal starvation and an increase in set-point for body weight could be explained in the same way as a plant that is extending its roots and taking in more nutrients. (See figure below)

When there is not enough nutrition, plants grow their roots deeper into the ground seeking more nutrients, and the same phenomenon occurs when we humans digest all the food in our entire intestines (or it may be the small intestine only), and intestinal starvation is induced.

(It is said that “the small intestine is the second brain” or that “it has a will,” and I clearly felt the will of my small intestine.)

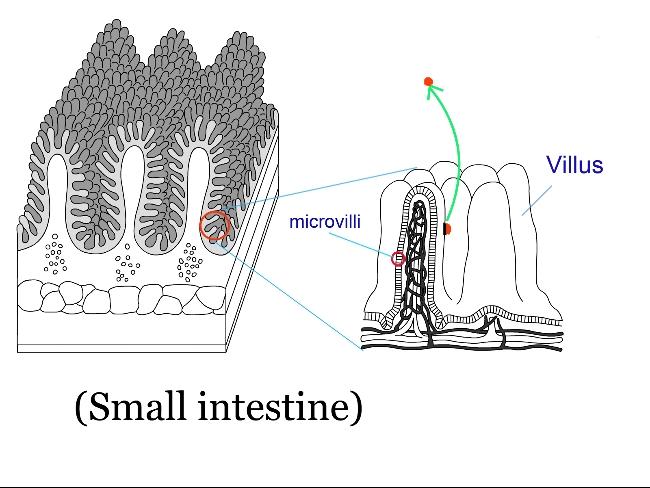

Actually the villi (*1) of the intestines do not grow, but I believe that the following phenomena occur:

(*1)In order to absorb more nutrients efficiently, the interior of the small intestine has a folded structure, with numerous protrusions called villi on its surface (Fig. 1). Additionally, microvilli develop on the surface of these villi.

It is sometimes said that if all of these were spread out, the surface area inside the small intestine would be equivalent to that of a tennis court.

<Fig. 1> Villi of the small intestine

First, I believe that the intestines (especially the small intestine) is the first organ to sense whether or not food is present. This is determined not only by the amount of energy, but also by how far the food has been digested. (For this reason, even if you eat a large amount, if your diet is heavily skewed towards easily digestible carbohydrates, intestinal starvation can be induced.)

When undigested substances, including fiber, remain in the intestines to some extent, the body perceives that “there is still food,” even if you're hungry. However, when all the food is digested (or very close to it), the small intestine sends a signal to the brain that “there is no food.”

In response, the body attempts to absorb more nutrients, and microscopic substances attached to the villi (or microvilli) of the small intestine detach themselves (Fig. 2). This, in turn, increases the surface area for absorption, thereby boosting absolute absorption capacity.

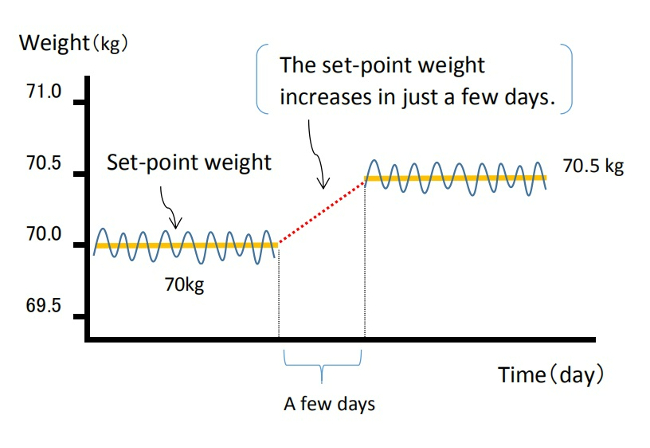

This causes weight gain, suggesting an increase in the set-point for body weight, and reaches a new equilibrium at a higher set-point within just three to four days.

<Fig. 2 >

In other words, weight doesn't gradually increase due to excess calories being stored bit by bit. Instead, the body normally maintains a stable set-point weight, but at some point, it suddenly jumps, whether by 300 grams or 500 grams, all at once (Fig. 3).

In summary, I believe that one of the key factors in the fundamental difference between obese and lean people involves their absorption ability.

[Related Article]

< Fig. 3 >

In Japan, obese individuals sometimes say things like, “I gain weight even just by drinking water.”

Of course, water alone does not make them fat, but I don't think it is totally wrong. It reflects just how efficient their absorption rate is.

3. What happens when one’s set-point weight is elevated?

(1) Once you gain weight, it becomes more difficult to lose weight

When your set-point for body weight goes up and you gain weight, it means that the balancing point, in terms of "energy- in, energy-out," has gone up, which can generate a more positive energy cycle and make it more difficult to lose weight.

When dieting, temporarily reducing the caloric intake to lose weight means reducing the "fertilizer" in the example of a plant. However, it is only a temporary weight loss, and you will likely return to your original weight when you start eating a normal diet again (the rebound effect).

Moreover, the reason why each time some people diet, they rebound and gain more weight than before is that skipping meals or eating light meals (not enough vegetables) can lead to intestinal starvation, which can further increase your set-point weight.

(2) More muscle, too

It is not that after you get fat, you gain muscle to support it. Since the overall absorption of nutrients increases, I believe that weight gain, at least to some extent, involves not only an increase in body fat but also lean mass such as muscle.

When a fat person loses body fat, they often have a thick, muscular chest or thighs. After body fat is gained, would the muscles around the chest and neck thicken to support that weight? (This varies widely from person to person.)

(3) Cause-and-effect reverse phenomenon

The increased intake of nutrients as a whole, including protein, creates a positive cycle of energy, which leads to the following phenomena.

Since digestive enzymes, hormones, etc. are also made from proteins (amino acids), it could enhance the ability to digest food and potentially bring about changes in the hormonal systems that regulate appetite and other functions. So, it is no wonder that people with larger bodies or stronger stomachs generally eat more than others.

There exists a cause-and-effect reversal phenomenon: people do not gain weight because they eat more, but because the bigger they are, the hungrier they become, and in turn, they eat more.

(4) Those who are overweight are prone to gaining more weight

Even if everyone eats exactly the same amount, people with big bodies-big, meaning large with some extra body fat or muscularly built-, or obese people, are more likely to feel hungry, which means that they eat relatively less, and they tend to gain more weight little by little.

It may be a vicious circle where a person eats modest amounts and gains weight, and if they skip meals or eat less to lose weight, they gain even more weight in the long run.

【Related article】→What Does It Mean to Eat Relatively Less?

On the other hand, if a lean person eats balanced meals three times a day, every day, he or she doesn’t induce intestinal starvation. And there is a good chance they will stay the same weight and have the same appearance for the rest of their life, regardless of caloric intake.

Therefore, "fatness" and "non-fatness," in this regard, are not due to obesity genes.

Also, for people like me who are very thin, being thin itself can reduce the amount of protein and other nutrients that can be taken in, thus a negative energy cycle continues. In turn, the muscles that support the stomach and intestines become weak and droopy, and the ability to digest food is also diminished by not secreting enough digestive enzymes.

This is a vicious circle where thin people can’t gain weight and remain thin.